From the Civil War to Chicago’s Mercy Hospital, the extraordinary history of Irish nuns in health care.

The Sisters of Mercy were the first women to go with Florence Nightingale during the Crimean War in 1854. They worked with her to make nursing more effective and to improve sanitary conditions.

In America, the Sisters of Mercy would make their impact on the battlefields in the Civil War, beginning a legacy in health care that is still going strong today.

“Veritable angels of mercy” are the words President Abraham Lincoln used to describe the nuns he saw tending wounded soldiers at one of the 25 military hospitals hurriedly set up around Washington to receive the more than 20,000 casualties – Union and Confederate – of some of the bloodiest battles of the Civil War.

“Of all the forms of charity and benevolence seen in the crowded wards those of the Catholic sisters were among the most efficient,” Lincoln wrote after visiting Stanton Hospital, staffed by the Sisters of Mercy, the order founded by Catherine McAuley in Dublin barely 30 years before. “More lovely than anything in art are the pictures that remain with me of these sisters going on their rounds of mercy among the suffering and dying.”

A nice sentiment, but by sanctifying these sisters he unintentionally diminished their human accomplishments. The 36 sisters who nursed at Stanton Hospital, near Washington, D.C., were not angels but women. Tough, determined, intelligent women with names like Murphy, Byrne, Ward, Leahy, and Maguire. Surely, they had to push themselves beyond their fears to face the horrors of war.

Six hundred nuns from twelve religious communities served as U.S. Army nurses during the Civil War.

They served on the battlefield and gave their lives. A group of Sisters of Mercy traveling to St. Louis on a Union steamboat took fire from a Confederate gun battery and worked through it, tending the wounded. At Gettysburg one St. Joseph sister wiped the blood-covered face of a young soldier to discover that he was her 18 year-old brother.

When the Sisters of Providence (the community I was a member of for six years) took over the military hospital in Indianapolis during the Civil War, they found, as hospital inspector Dr. John M. Kitchen would write in a report, “a miserable state of filth and disorder, the sick in wretched conditions,” and would go on to create “a clean comfortable house for the sick soldiers . . . Whatever success may have attended our efforts is due in great degree to these meek and worthy women.”

Worthy? Yes. Meek? No. The orders who sent their sisters to the front line did so despite the fact that Dorthea Dix did not want them. All biographical information on Dix, who had been appointed by the U.S. government to recruit nurses, mentions her anti-Catholicism. She refused to accept Catholic women and nuns as nurses.

But nuns were already operating 30 hospitals around the country, and the doctors and public officials who knew their work by-passed Dix and welcomed them.

The Irish Sisters of Mercy, like orders of Polish, German and Italian, opened their hospitals to all no matter their religion, background or ability to pay.

The Sisters of Mercy in Chicago, who founded Mercy Hospital in 1847, also founded a nursing academy and subsidized the hospital with the tuition collected from the young women in their academic programs.

A great number of the hospitals and education academies throughout the U.S. were built with money raised by nuns. Yet they were always at the mercy of the bishops. In 1871, Mother Theodore Guerin, the French founder of the Sisters of Providence, was excommunicated by Hal Italiandiere, the local bishop, for refusing to hand over the deed to Saint Mary-of-the-Woods women’s college in Indiana. She appealed to Queen Amelie of France, the bishop was replaced, and she was reinstated.

In 1864, Bishop James Duggan of Chicago, whose sister Mary Jane was a Mercy nun, decided to take over Mercy Hospital and gave the Sisters two days to evacuate their patients. Led by Mother Frances Monhalland, the nuns moved 100 sick and dying people to St. Agatha’s Academy, which would become the core of the new hospital.

As it turned out, the bishop’s hospital burned down in the Chicago Fire of 1872 and the new Mercy Hospital was much needed. By that time Bishop Duggan had been institutionalized as mentally incompetent.

In the years following the Civil War, nuns established 800 hospitals, the basis for a network of Catholic hospitals that now serves one in six patients, the largest private group in the U.S.

Two recent books tell that story. John Flalkas in Catholic Nuns and the Making of America looks at the service of nuns, especially the Sisters of Mercy in the West, including their encounters with Billy the Kid. In Collect to Serve: A History of Nuns in America, Margaret M. McGuinness documents the growth of religious orders. In 1968 there were about 204,000 women religious in the U.S. Most were involved in education, staffing the largest parochial school system in the world, while running 10,000 of their own schools, colleges and universities. But we’re going to focus on the nuns in health care.

Chicago’s Mercy Hospital is an example of how these early pioneers continue to inspire and shape patient care today.

Sister Sheila Lyne, R.S.M., first served as a C.E.O. and president of Mercy Hospital and Medical Center from 1976 to 1991. She left when Mayor Richard N. Daley asked her to become Chicago’s Commissioner of Public Heath, the first non-doctor to hold that post. She returned to Mercy in 2000 because the male team hired to succeed her had mismanaged the hospital into near-bankruptcy. She turned Mercy around, and this year, helped negotiate a merger with the Trinity Health Corporation, one of the nation’s largest hospital systems. It is comprised of many facilities founded by Religious Sisters, and will provide Mercy with the funds necessary to continue its mission.

Sister Sheila, 77, just turned over her CEO position to Carol Schneider but she will remain on the Mercy Foundation board. When we spoke, she was readying herself for a trip to Ireland. She would visit family in Killarney and enjoy a retreat at the Mercy Convent on Baggot Street, Dublin, where Catherine McAuley had begun her ministry, and with whom Sister Sheila shares a bond.

“When Catherine McAuley was a young child her father told her, ‘You must go out every day and feed the poor’ and my father told me the same thing,” Sister Sheila said. “He was from Killarney, Ireland, and he was a strong union man. I remember right before he died at 86, I said, ‘Maybe the day was over when it took a union to make employers do the right thing.’ And he gave me this look like ‘You can’t teach her anything!’ He was a really good man.

“Catherine McAuley’s father died when she was five but she never forgot that lesson. We [Mercy nuns] have emulated her. Not perfectly. You can’t take care of everybody, and yet can we send people away? I don’t think so. Even though I’m officially retired now I’m around the hospital a lot and I keep my eyes open to make sure no one is turned away because they can’t pay.

“Mercy has never made a distinction between those who can pay and those who can’t. That’s the spirit here and the doctors are part of it. In the 1980’s we decided to employ our physicians so they became a part of the hospital and even though they may not earn as much here as in other places, we don’t have many who leave.”

Sister Sheila grew up in Chicago’s Little Flower Parish and went to Mercy High School. She remembers, “The Sisters were so dominant in and of themselves. Their attitude was, this is what should be done, do it. And they did. I wanted to be a sister and a nurse but wasn’t sure if I could do both, as most of the sisters worked in education and only a few got to train as nurses. Two of us got chosen from my group and I was one. And then soon after I finished Basic Nursing, President John F. Kennedy decided we needed more psychiatric nursing care and made grants available. We had a sister very active in health care trends and she was right there. So we got money to train eight individuals – six lay people and two sisters and I was one of them.

“After I got my Master’s I went to our hospital at Davenport, Iowa. At that time the Sisters of Mercy had 69 hospitals. After a few years in Iowa, I came back to Mercy Chicago. There always has been a psychiatric unit at Mercy hospitals. The tradition started with soldiers suffering from shell shock after World War I. The sisters also opened a unit to treat those suffering from venereal diseases. That’s how the Sisters work. If that’s the disease you have, that’s what we’ve got to take care of.”

Sister Sheila became head of the hospital in 1976 and held that position until 1990. “And then Richard Daley, who, by the way, was born in this hospital, asked me to help him find a doctor to head up the City Health Department. A doctor always held that post. But as the Mayor looked, we’d meet and I’d give him suggestions about the department until one day he said, ‘Why don’t you take the job?’ So I did. I was there until 2000, and I’m happy that we were able to bring down the state of infant mortality from 17 in 100 to 10 in 100, though it should be two or three. And I greatly increased the funding for AIDS patients.”

In 2000, Mercy needed Sister Sheila again. She didn’t elaborate on the financial crises or her role in solving it, but she spoke vehemently about one proposed solution for Mercy Hospital.

“When Loyola University was moving their Medical Center to the suburbs they wanted us to move out with them. But how could we leave Chicago? We were born and raised here and have served the city since 1847. There were those who urged us to move so we’d get away from poor people. But we’re not running from the poor! What would Catherine McAuley think of us if we did?”

It was hard to get Sister Sheila to talk about her own accomplishments, but you can’t spend any time at Mercy Hospital without hearing stories of sisters in charge.

Dr. John Picken has been on the staff at Mercy Hospital for nearly 50 years as an obstetrician and gynecologist. He and his wife Ginny live a five-minute walk away. John got his first job as a medical student in 1959.

“I applied to the medical records office and the Sister in charge hired me. She was very old but surprisingly innovative. In those days every time you got admitted to the hospital you got a new medical record number and your papers would be filed away. And of course no one could find them the next time. Sister invented the idea of a Universal Lifetime Medical Record Number. She was preparing for electronic medical records long before computers existed, and also divided charts into sections so all the information could be found easily.

“I also remember that all the hospital security at night consisted of was one large nun and her German Shepherd. Believe me, no one got past them.

“When I started here as a doctor every one of the 16 nursing units had a nun in charge – Surgery, OB, Emergency Room, Finance, Supplies, Billing – everything. And their convent was on the top floor of the hospital so they were available night and day, 7 days a week. And they wanted to be awakened if they were needed.” The nuns didn’t just have excellent skills. They were compassionate and caring, but they also had tons of good business sense.

Picken recalls that when Sister Sheila came back to take over Mercy in 2000 after a disastrous period of mismanagement by CEO and CFO there was only enough money for 60 days of salaries. “We were 60 days from closing,” Picken said. “The CFO had closed the billing department so the hospital wasn’t getting reimbursed. Sister Sheila had enough clout so that when we submitted our back bills to Medicare, Medicaid and the insurance companies, they paid up. She found we weren’t getting the correct bed-per-day payments from one of the biggest insurance carriers. She had a meeting with them and said, ‘You know you’re doing wrong. Now you can redeem yourselves.’ And they did.”

Ginny Picken, a Feldenkreis practitioner, talked about Sister Sheila’s hands-on approach. “The Feldenkreis method [a therapy used to improve health through increased awareness of movement] can dramatically help children who suffer from various palsies. I was working with a little girl who was making enormous progress, but her mother had very limited resources. I showed Sister a picture charting the child’s improvement. ‘We’d be stupid not to support this [method]. It works,’ she said. She went and got a grant so that I could continue to work with the child.”

Ginny, who is married to Dr. Picken, produced and directed a documentary called Promises To Keep to mark the 150th anniversary of the hospital. Promises highlights the amazing foremothers of the hospital, including Sister Mary Agatha O’Brien, a young woman from County Carlow, who was one of the seven Sisters of Mercy who left Ireland for the wilds of Pittsburgh in 1843. Four years later, she led a group of five religious to Chicago.

She was 24, the oldest of the five. Two were novices, and two postulants. One novice, Sister Mary Vincent McGirr, would head the group of nuns that established Mercy as the first permanent hospital and first teaching hospital in Chicago. Her doctor brother joined her at Mercy. Sister Mary Vincent was the only one of the original five to survive the rigors of the frontier. The others died within 10 years, but not before they’d established the first high school in Chicago, as well as three other schools and an orphanage.

And then there was Mother Mary Frances De Sales Monhalland, an Armagh native who arrived in Chicago to join the Sisters in 1847. She had run her father’s grocery business in New York, and her business acumen became essential to the Sisters’ mission. In a time when women could not own land, she set up a corporation to hold the Sisters’ property, thus protecting their schools and hospitals from more takeovers by male clergy. She was the visionary who raised the money to build and expand Mercy Hospital and the many Mercy education institutions.

Then there was Sister Mary Ignatius Fenney, the first woman pharmacist in Illinois. She was the only woman among a group of forty to sit for the first licensing exam, and one of only three who passed.

Another innovator was Sister Mary Ethelrida O’Dwyer who became the first woman anesthetist and worked with Dr. John B. Murphy, who pioneered surgical breakthroughs that changed medicine. The list of heroic sisters goes on and on and the stories accumulate.

One favorite of all the Mercy stories is from 1904, about a man who was hit by a streetcar. He was brought to Mercy and cared for though he could not pay. Months after his release, a letter arrived from a Mr. Ferris Thompson, a friend of the man who had been treated. He enclosed a check for $250,000. Thompson was the son of a New York banker. He’d married a countess and moved to Paris. Every year until 1945, a check for $5,000 arrived and then a final bequest of $200,000. The money went toward housing the newly set up school of nursing – another first.

“The philosophy of Mercy Nursing is inspired by Catherine [McAuley] and based on unconditional love, tenderness – engaging the heart and soul of the nurse in the work of caring for all we serve,” Ginny explained.

I asked Nurse Eileen Knightly, the director of the Sister Sheila Lyne Breast Center, how that philosophy worked in practice. She cited the atmosphere and design of the Center – quiet, comfortable and private. – as examples. She also pointed to a sign on her wall that says in effect, If you don’t like our customers you’re in the wrong job. “Patient satisfaction comes first,” she says. Eileen has been at Mercy since her teens, and her story of Sister Sheila concerns meeting the hospital director on a stairway. “I was 16, working as a ward secretary, the lowliest of more than 1.500 employees. ‘How are you, Eileen,’ Sister Sheila said. She knew my name! She knows everyone’s name!”

My last stop at Mercy Hospital was on the green roof, planted with wildflowers and grasses of the Illinois prairie – tamed now and a very different place from the wild frontier town Chicago used to be. And yet challenges remain. Abraham Lincoln concluded his discussion of the Sisters of Mercy by saying “they had the courage of soldiers” with only “hope to sustain them in contact with such horrors.”

In 2010, at another Sisters of Mercy Hospital, St. Joseph’s in Phoenix, Sister Margaret McBride, a member of the hospital’s ethics board, acquiesced with a medical decision to terminate the 11-week pregnancy of a 27-year-old mother of four. Neither she nor her baby had any chance if the operation was not performed. When Bishop Thomas Olmsted heard of this he declared Sister Margaret excommunicated. The media descended and she was caught in a controversy that almost destroyed her life. Yet Sister Margaret found healing through a conversation with the young mother whose life had been saved.

The woman made a return visit to the hospital in 2011 and asked to see Sister Margaret. “ I walked into the room and burst into tears and so did she,” said Sister Margaret. ‘You saved my life. I’m sorry all those terrible things happened to you because of me,” the woman said. And I told her I had received lots of support from the doctors, the employees, the board of directors and Catholic Health Care West.

“In some wonderful and beautiful way when you go through challenges and difficulties, grace comes. I never would have realized that except for this experience,” Sister Margaret said. She reconciled with the Church and the excommunication has been lifted. The bishop required that she go to confession and resign her position, which she did, but she is now back on the staff of the hospital. She remains with the Sisters of Mercy who supported her during her ordeal.

The hospitals that the Sisters of Mercy and other religious orders of nuns, brought into being more than a century ago, continue to serve the public. Though the nuns who maintained them have passed the torch to a new generation, the legacy of Catherine McCauley, who started a movement that at one time had nine thousand hospitals, endures throughout the country.

Note: Sister Sheila arrived in Ireland in July for the best weather in 100 years. I’m sure the sun was shining in Killarney when the Lynne clan gathered and there probably were some angels around too.

Hi. I read your article with great interest. An ancestor of mine was also a Nun in America. Can you help me to trace what order she was in and what part of America she went to? Many thanks for any response you may make.

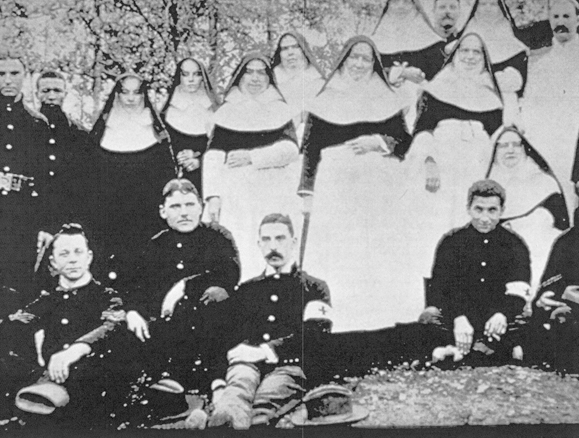

Great article! I will note however, that first photo of Sisters of Mercy with soldiers is from the Spanish American War, not the Civil War.

Amazing History thank you for posting like most of this History it is largely ignored why ? the people are Women, Irish and Catholic that doesn’t fit today’s narrative. But the facts are there for the experienced historian to discover . History doesn’t lie .