Molly McCloskey, the author of Circles Around the Sun, shares how one profound reading experience led her to better understand her older brother who suffers from schizophrenia.

I can still recall, in the way one recalls the most powerful reading experiences of one’s life, lying on the bed in my studio apartment in Portland, Oregon, and reading “The Metamorphosis” for the first time. I was twenty-three years old, the age my eldest brother was when, in 1973, he was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia.

By 1987, the year I was living in that studio and reading Kafka, Mike’s illness had passed through its more florid stage. He was on a good deal of medication, and his life, if extremely limited in scope, had at least acquired a certain stability. His hospital admissions were a thing of the past. He was in subsidized housing on the other side of the city. He was thirty-seven years old. I did not see him often, usually only if my mother was visiting from the East Coast.

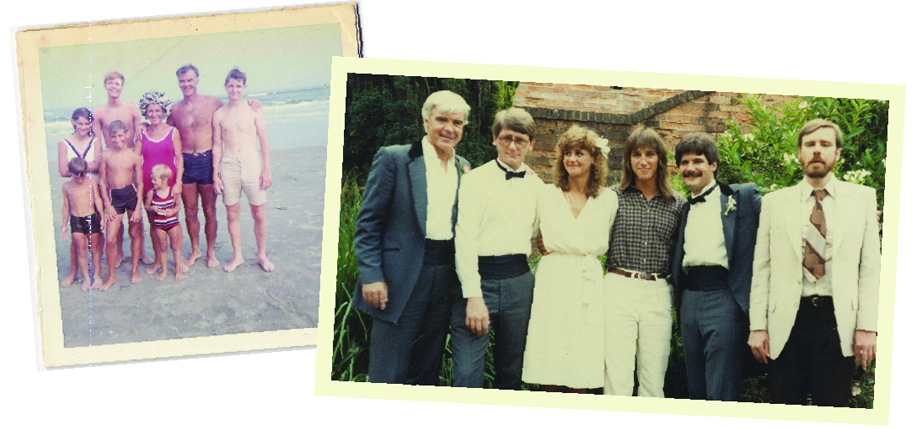

But in a sense, I had never known him. There are fourteen years (and four siblings) between us. I was too young to remember him before he became ill, and I grew up and into adulthood taking it on faith – on the evidence of photographs and family lore – that he had once been a beautiful, bright boy of enormous promise. Perhaps it is because I did not know him that the things that down the years spoke to me of him often came from unexpected sources, and that they spoke to me obliquely, associatively, metaphorically.

Kafka’s famous short story opens with the line, “As Gregor Samsa awoke one morning from uneasy dreams he found himself transformed in his bed into a giant insect.” Gregor’s transformation is a fantastical conceit embedded within an otherwise realistic story; there is never any explanation of why or how the change occurs, though Kafka tracks it in detail – beginning with the horrifying image of Gregor lying on his back that first morning, trying in vain to control his numerous legs, which are now waving helplessly before his eyes. Over the next fifty or so pages we witness the fallout of his metamorphosis from human to a being – physically, at least – other than human.

Gregor is a traveling salesman, living in an apartment in Prague with his mother, father and sister, all of whom are dependent – or so he believes – on his wages. Initially, each of the three family members reacts differently to the fact that Gregor is now a very large insect (large enough to stand on the lowest pair of his legs and turn the door handle with his jaw), though not one of them, understandably, is comfortable with the change. Shock, fear, pettiness, revulsion, shame, anger, impatience – these are the emotions that dominate.

But if Gregor’s situation evokes little compassion within the family, it summons enormous compassion from the reader, in large part because we see events unfolding from Gregor’s point-of-view. The figure who appears in so many stories, films, fairy tales as the inscrutable and frightening “other” – disrupting normality, throwing all into disorder – becomes here our eyes and ears on the world. (The story is told not in the “I” of the first person, but in the “close third” – the point-of-view of a single character prevailing, and prevailing here until near the story’s end, when Gregor dies). This point-of-view is possible because even though Gregor has changed outwardly beyond recognition, he remains capable of human feeling and thought. It may be said, in fact, that as the story rolls on, Gregor’s humanity intensifies in inverse proportion to his family’s growing callousness and indifference.

Crucially, Gregor does not retain the capacity for speech, and one of the most heartrending aspects of the story is the fact that he can understand what his family is saying about him, while his own voice has been rendered alien. The family, crowded outside the locked bedroom door that first morning, is horrified by the sound. The “chief clerk,” who has come to find out why Gregor hasn’t appeared for work, is heard to say: “That was no human voice.”

Gregor, mistakenly, takes solace in their response: “Yet at any rate people now believed that something was wrong with him, and were ready to help him . . . He felt himself drawn once more into the human circle and hoped for great and remarkable results from both the doctor and the locksmith. . .”

Alas, Gregor’s intimations could not be more wrong. His ostracization from the human circle has only just begun. He opens the door, his mother falls to the floor in shock, the chief clerk flees in disgust. His father knots his fist, “as if he meant to knock Gregor back into his room,” then weeps until his chest is heaving. Gregor retreats to his bedroom. For the next forty or so pages, he will report to us from his strange locked-in world, alone, unrecognizable, helpless to intervene in his own fate – and yet possessed of human sensibilities and sensitivities.

At the time I read this story, it had been fourteen years since my brother’s illness was diagnosed. For much of the first few years after the diagnosis, he had lived in the family home. During those years, he spent an enormous amount of time in his bedroom, mostly in bed, fully dressed, under layers of blankets and often wearing a woolen hat. Medication to quell the psychotic episodes was no doubt taking a toll on his energy levels, and he was almost certainly depressed. He was also extremely apathetic, one of the so-called negative symptoms of schizophrenia. I imagine that his bedroom was for him a refuge from the churning world – from over-stimulation, from expectations he could not meet, from the squealing antics of his adolescent sister and her pals, from the strapping good health of his teenage brother.

For me, that bedroom was a site of mystery, its closed door a seal on a world I could not imagine and of which I wanted no part. When I think of my brother’s transformation from golden boy – he was an honor student and an athlete who attended Duke University on an academic scholarship – to a young man in the throes of serious mental illness, I think of his bedroom in the house on Fourth Street. I think of how time must’ve weighed terribly on him during those long, dull medicated days. And I think of myself, sitting in the living room and seeing the bedroom door swing slowly open, and I recall how I would flinch a little, for as unnerved as I was to think of him lying in there all day, I was just as unnerved by the prospect of facing him. My brother was never violent or aggressive. But he was, understandably, seldom in a light or a friendly mood, and his presence and his appearance and his often strange utterances were disconcerting. They also made me feel guilty of something – frivolity and good health, I suspect.

Those were the years of upheaval and uncertainty, when the illness as a permanent debilitating presence seemed not yet a fait accompli. When those long spells in bed were interspersed with periods of lucidity, what appeared to be fresh starts. My mother, in an effort to support any sign that a recovery, or a partial recovery, was possible, must have moved a hundred times between hope and the effort to check that hopeful impulse, as a kind of protection against the soul-destroying effects of witnessing yet another psychotic break. The soul-destroying effects were not, of course, limited to her – Mike himself must have felt them, the terrifying, painful frustration of having everything fall apart, all over again.

About midway through “The Metamorphosis,” there is a scene in which Gregor’s sister, who has taken over her brother’s care and feeding, decides that in order to give Gregor as much room as possible for crawling about she might remove the bedroom furnishings – which Gregor, in his present incarnation, has no use for.

To do this, she enlists the help of her mother, who enters Gregor’s room for the first time since the change. (Gregor, not wanting to upset his mother, makes sure he is covered by a sheet, thereby renouncing the pleasure of seeing her.) Once in the room, Mrs. Samsa begins to doubt the wisdom of the enterprise: “. . . doesn’t it look as if we were showing him, by taking away his furniture, that we have given up hope of his ever getting better and are just leaving him coldly to himself. I think it would be best to keep his room exactly as it has always been so that when he comes back to us he will find everything unchanged and be able all the more easily to forget what has happened to him.”

On hearing his mother, Gregor experiences a new shock, when he realizes how thoughtlessly he had been in favor of the plan to have his room made empty. “Did he really want his warm room, so comfortably fitted with old family furniture, to be turned into a naked den in which he would certainly be able to crawl unhampered in all directions but at the price of shedding simultaneously all recollection of his human background?”

This passage causes me a particular shiver.

At what point does one give up hope? What does giving up hope even mean in a context of chronic mental illness? Might it sometimes be a form of compassion – the acceptance of a new reality, the acceptance of another not as one would like him to be, but as he is? Can refusing to give up in fact be a kind of unintended cruelty? How do you know? How do you know you aren’t giving up just at the moment your unwavering belief in someone’s “recovery” (whatever that might mean under the circumstances prevailing) might’ve helped to lay the foundation for it? These aren’t questions with answers. I am certain they are questions my mother grappled with.

The point is not to liken my brother to Gregor Samsa, nor to liken my family to the Samsa family; nor is it to suggest that “The Metamorphosis” is a story about mental illness. (The “aboutness” of any story comes down to the big abstract nouns – love, death, loss, betrayal, fear, desire, identity, isolation, joy – realized through anecdote, and we bring to those abstractions our own histories and psychologies.) “The Metamorphosis” renders its world with such precision while resisting a single interpretation; it insists on its own openness.

The point is rather the way in which the story, when I first read it and on subsequent readings, seemed to cut through layers of my habituated point-of-view. I felt I had been dropped through a trap door, and wherever it was I’d landed, it seemed like a place a little closer to my brother.

This is presumptuous, of course, because really I know nothing of my brother’s inner world, or of what he has suffered. But I felt something I hadn’t much felt before: the beginnings of curiosity, the desire to better understand what it was that had befallen him, what it was that he had lost – which is to say, I hope, that I felt the beginnings of compassion. I saw in Gregor’s isolation – physical, intellectual, emotional – a glimpse into the terrible, transforming effects of schizophrenia, an inkling of just how lonely, excluded, and afraid my brother must have felt as he watched himself receding from a world he had known and loved and in which he had thrived.

I was not prepared for what “The Metamorphosis” made me think and feel. But this is the opportunity literature offers us: to step outside of ourselves. Reading doesn’t make us moral, by any means; it only offers us other ways of experiencing the world, alternative points-of-view. But this is no small offering: it is the necessary starting point of empathy, and of compassion.

Leave a Reply