Edythe Preet writes that music defines Ireland’s identity.

For every country there is an iconic image that immediately brings the nation to mind. The United States has the Statue of Liberty. Dragons evoke thoughts of China. The Fleur de Lis is quintessentially French. While national symbols range the gamut from mythical beasts, crowns, and statues to insignias, monuments, buildings and more, music is conspicuously absent. Except in one case.

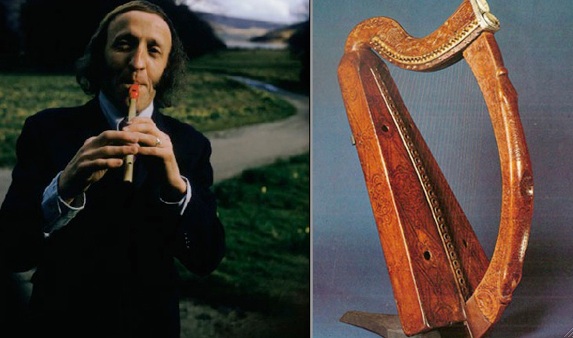

Of all the world’s nations, only Ireland’s state identity is linked to a musical instrument. The Harp. As the country’s official emblem, it is found on the presidential seal, passports, the 5-cent euro coin, official documents, the flag of Leinster, and the seal of Ireland’s National University. Businesses, too, use the Harp in their logos as a way to brand their ‘Irishness.’ Ryan Air shows the instrument on the tail of its airplanes, and as anyone who’s ever visited an Irish pub knows, the Harp is imprinted on every glass, can, bottle and barrel of Guinness Stout.

When the harp arrived in Ireland is uncertain, but its history dates back at least 1,000 years. Legend holds that the first harp was owned at the dawn of time, by Dagda, a chief of the Tuatha de Danaan. Lost temporarily during a war with the evil Formorians, when it was recovered the harp had the ability to call forth winter and summer. And thenceforth, whenever the Dagda played it, he could produce melodies so poignant, sweet or calming that the music would make his audience weep, smile or sleep.

During Medieval times, the retinue of every Irish king and chieftain included a resident harp player whose music was the principal entertainment at feasts, as well as accompanying poetry recitations and the singing of psalms. With a sounding chamber carved from a single log, usually willow, and brass strings, the Irish harp when plucked with the fingernails produces a clear melodic sound. The oldest example of the Irish Harp is housed at Dublin’s Trinity College. Some claim it belonged to the last High King of Ireland, Brian Boru (d 1014) who is said to have been an accomplished harpist.

Through the centuries the harp stood as such a cultural Irish icon that during the Cromwell Era it became a symbol of resistance to England, and Queen Elizabeth I issued an order to hang all Irish harpists and burn their instruments. The edict gave rise to the famous poem “The harp that once through Tara’s halls the soul of music shed, now hangs as mute on Tara’s walls, as if that soul were fled. So sleeps the pride of former days, so glory’s thrill is o’er, and hearts that once beat high for praise, now feel that pulse no more.” Thankfully, a new generation of Irish harpists is bringing back the sweet sound of Ireland’s most symbolic musical instrument.

Two other time-honored Irish musical instruments are the tin whistle and bones. One of my father’s favorite recitations went like this: “When I was a child my Ma gave me a wooden whistle, but it wooden whistle; then she gave me a steel whistle, but it steel wooden whistle; then she gave me a tin whistle and now I tin whistle!” A simple six-holed woodwind, the Tin Whistle is a flute-like instrument found in most cultures, the earliest example of which dates from the Neanderthal era. While the oldest ‘whistles’ were made from wood or bone, during the Industrial Revolution they began being manufactured from rolled tin. Often called a ‘penny whistle,’ the term doesn’t refer to the instrument’s cost but rather the fact that whistlers were once paid a penny a tune. Today, the tin whistle is a popular instrument that often introduces the start of a reel, and handmade examples can cost several hundred dollars.

Of all Irish traditional instruments, Bones are the most ancient. In their most elemental form, Bones are exactly that: sections of animal rib bones or leg bones. They are usually 5-7 inches in length and somewhat curved. Played by being held loosely between the fingers, their distinct sharp sound provides a rhythmic clacking background to a tune’s melody. While some really adroit bones players can hold a set in each hand and create contrapuntal rhythm, Irish bones players are unique in that they use only one set.

Unlike the aforementioned instruments, the handheld drum called a Bodhran does not have an ancient musical past. Its construction consists of a goatskin tacked to one side of a circular wooden frame measuring 10-18 inches across and 3.5-8 inches deep, and it is played either with the bare hand or a small carved wooden stick called a ‘tipper.’ Some historians theorize that the Bodhran may have been derived from a tambourine; others claim that it was originally a tool used to separate grain from chaff when gathering wheat and may have been ‘drummed’ in annual harvest rituals.

Whatever its origin, the Bodhran emerged as a key Irish instrument during the ‘roots’ revival of traditional music that began in the mid-20th century and it has provided the backbone beat for every Irish music group ever since. A dear friend who plays the bodhran masterfully is a member of The Dublin Four (www.thedublin4.com), a group of Irish ex-pats living in Los Angeles who play the music they grew up with. Having attended numerous of their performances, I have had the opportunity to really study the playing of the bodhran. Where once I through it was a simple task, I now know that a fine player can coax a wide spectrum of sounds from this simple instrument.

The other musical instruments identified with Irish music – the fiddle, guitar, and banjo – are not Irish at all, but they have been embraced by Irish musicians so lovingly and wholeheartedly that no set of Irish music would be complete without them.

One of the most enjoyable ways to experience the music of Ireland is to stop by an Irish pub when the music’s on, the craic’s high, and the Guinness is flowing! Raise your glass emblazoned with the Irish Harp, toast the great tradition of Irish music, and be sure to sample some delicious pub grub. But that’s another story! Sláinte!

Recipes. If there’s no Irish pub in your region, you can still enjoy the experience of listening to great Irish music and nibbling on delicious pub grub! Just pop a CD in your music machine and whip up some of the recipes below!

Angels on Horseback (personal recipe)

1 pint oysters, shucked

Bacon strips

Wooden toothpicks that have been soaked in water for one-half hour

Preheat broiler. Wrap each oyster in a bacon strip and secure with toothpicks. Large oysters can be cut in half before wrapping. Broil until bacon is cooked, turning at least once so bacon cooks evenly. Serves 4-6 as an appetizer.

Shepherd’s Pie (personal recipe)

3 pounds ground lamb, beef OR turkey

2 large onions (diced)

4 tbsp flour

2 tbsp olive oil

1 tsp fresh parsley, minced

1 tbsp fresh rosemary, minced

2 cups chicken broth

2 cups frozen mixed carrots & peas

8 Idaho potatoes, peeled and diced

1 cup milk

4 tbsp butter

Heat olive oil in a large pot. Add ground meat and brown. Pour off extra grease and add onion. Cook for 5 minutes, or until onion is soft. Add flour, mix well and cook for 5 minutes. Stir in chicken broth, and simmer for 10 minutes. Add fresh herbs, peas and carrots. Season to taste with salt and pepper. Remove from heat and pour into buttered 9×9-inch baking dish. Set aside. Place potatoes in a large pot, bring to boil in salted water to cover, and cook until potatoes can be pierced easily with a fork. Drain off water, cover and steam until potatoes are dry. Add butter and milk then mash. Spread mashed potatoes over meat mixture in baking dish. Broil for 3-5 minutes until potatoes are golden brown. Serve with crusty bread and butter. Makes 4-6 servings.

Rustic Apple Tart (personal recipe)

1 1/4 cups flour

1 tsp sugar

1⁄2 tsp salt

1 stick cold butter, cut in small chunks

1⁄2 cup ice cold water

6 large apples, peeled, cored & cut in chunks

1⁄3 cup golden raisins (optional)

1 tbsp sugar

1⁄4 tsp cinnamon

1 egg yolk

1 tbsp heavy cream

Combine flour, sugar and salt. Cut butter into flour mixture until the texture is grainy (a food processor does the job nicely!). Remove to a large bowl, pour in water gradually and gather into a dough ball. Pat out into a 1-inch thick circle, wrap in waxed paper and refrigerate for at least 1 hour. Turn dough onto a floured surface and roll out until approximately 1/4 –inch thick. Fold into thirds from the sides, then fold top and bottom to middle. Roll out again until four inches larger than a 9-inch pie pan. Place pastry in pie pan with extra hanging over the sides. Mix apples with raisins, sugar and cinnamon and place in the pie pan. Fold edges of pastry up leaving an approximately 3-inch open circle in the middle. Mix egg yolk with cream. Use a pastry brush (or your fingers) to paint the pastry with the egg mixture. Bake in a preheated 350 F degree oven. Cover with aluminum foil after the first 20 minutes so steam will cook the apples. Remove foil after 30 minutes and continue baking until pastry is golden brown. Makes 1 tart.

____________

This article was published in the June / July 2013 issue of Irish America. ♦

Leave a Reply