In the male-dominated field of Irish writers, Mary Lavin was a pioneer. Daphne Wolf examines Lavin’s American roots and the influence they may have had on her work and spirit.

Cleaning out old books from my parents’ house, I salvaged a yellowed paperback titled Irish Short Stories and Tales (with a price tag of 35¢). Inside were stories by James Joyce, George Bernard Shaw, Sean O’Faolain, Frank O’Connor, Liam O’Flaherty and Oscar Wilde. Of the 32 celebrated Irish authors whose works were represented, only one was a woman. And she was born in East Walpole, Massachusetts.

That Mary Lavin ever shouldered her way into this Irish all-boys’ club is thoroughly amazing. As her 1996 obituary in The Independent observed, her writing had always been “confronted by the distinctly male genre of the short story,” whose masters “had virtually established copyright on what an Irish story should be.”

Lavin had her own ideas about that. Unlike her male counterparts, she never wrote about Ireland itself, either politically or historically, although nearly all her stories take place there. Her characters were people who just happened to live in Ireland, often widows or single women, whose lives were marginal and of little consequence to outsiders. It seems a great wonder then that her story “The Widow’s Son” was included in my wee 1957 volume at all. Of course, that is the disturbing part too.

She was a woman in a male-dominated genre, who first saw Ireland with the gaze of an American girl. According to her son-in-law, Irish novelist James Ryan, Lavin reveled in her ability to hold two opposite views about a topic without ever having the desire to resolve them. Just so, her stories embraced the paradoxes of gender and geography that kept her from fitting neatly into any mold, infusing her work with a timelessness that keeps it provocative and fresh today.

The 100th anniversary of her birth in 2012 sparked much attention to Lavin’s writing, beginning with the re-publication of two collections of her stories: Tales from Bective Bridge (Faber and Faber), and Happiness, and Other Stories (New Island Books).

Last April, Irish writer Colm Tóibín spoke on Lavin at a symposium, “Mary Lavin Remembered,” at New York University’s Glucksman Ireland House, where he was joined by American writer Mary Gordon and NYU Professor of Irish Studies Greg Londe.

This spring, the annual Elizabeth Shanley Gerson Irish Literature Reading at the University of Connecticut hosted “Mothers and Daughters,” a tribute to Lavin and her daughter, the late Irish Times literary editor Caroline Walsh. James Ryan, who was Walsh’s spouse, introduced readings by Irish writers Anne Enright and Belinda McKeon, and a talk by Tóibín. The setting was apt, as Caroline and her mother had lived there when Lavin was the university’s first writer-in-residence, in 1967-68 (she returned again in 1970-71), and there were audience members at the event who remembered them both.

Lavin’s talent gleamed in the format of the short story; she compared it to “an arrow in flight, or…a flash of forked lightning…all there on the sky at once.” Published in magazines like The New Yorker and The Atlantic Monthly, and in numerous collections, her writing earned many prizes, like the James Tait Black Memorial Prize, two Guggenheim Fellowships, and the Katherine Mansfield prize. She was president of the Irish Academy of Letters and a Saoí (granted for “merit and distinction”) in the elite association of the Irish arts, Aosdána.

At the Gerson Reading, Ryan recalled how Lavin loved to take the floor at parties to tell stories. Her second husband, Michael Scott, was always urging her to stop wandering off on tangents and finish her tale. “A story has a beginning, a middle and an end,” he would remind her. “Yes,” Mary agreed, “but not in that order.”

That was her way of writing a story too, Ryan said, and she would “keep whatever was central to that story out of the story, and go round and round and round and round until that center began to emerge of its own accord.”

Being born in America skewed the way Mary Lavin saw Ireland. Even though she had lived in Ireland since 1921, returning to the United States only for visits and for her terms at the University of Connecticut, the fallout from her Yankee childhood swirls silently inside her stories. She was Irish yet, in the words of writer and critic Seamus Deane, “She wears her Irish rue with a difference.”

Lavin’s parents never would have met – or married – if they had not left Ireland in the first place. They met on the high seas, traveling in reverse from America to Ireland. According to Leah Levenson’s biography, The Four Seasons of Mary Lavin, Lavin’s mother, Nora Mahon, the daughter of a prosperous merchant family in Athenry, County Galway, was on her way home after an unsuccessful trip to the U.S. to find a husband. Tom Lavin, a poor emigrant from Frenchpark, County Roscommon, was far from Nora’s ideal choice, but, after three years of relentless courtship, she agreed to marry him and sail back to America.

Bitterly homesick in East Walpole, Massachusetts, Nora took every chance she could to return to her family in Galway, immersing Mary’s early life with the normalcy of darting back and forth across the Atlantic Ocean. Being at a physical distance from Ireland had provoked unforeseen options for her parents, and the miles of salt water in Lavin’s pedigree gave her something other Irish writers could not claim: the detachment of an outsider’s eye.

Lavin returned with her mother to Ireland permanently when she was 9. In a 1979 conversation with Irish writer and scholar Maurice Harmon, Lavin said the move to Athenry decided her future career:

“How great a shock it must have been to the eyes and ears of a child to leave that small town in Massachusetts and in a few days arrive in a small town in the west of Ireland. For all I know it was the shock to eye and ear that made me a writer. The kind of person who writes is born. I never wanted to be a writer, never, never, never.”

In Athenry, thrust into her mother’s large and opinionated family, Lavin confronted many cultural changes as well: farm animals in the streets, a less rigorous curriculum at school, and no electricity. In the 1992 RTÉ film, An Arrow in Flight: A Tribute to Mary Lavin, Caroline described the experience as “being catapulted” into a place where her mother’s entire world was challenged. From the start Lavin was “picking it all up…seeing inequities…seeing poverty and…the pain of emigration.”

Catholicism was different, too. In East Walpole, she had gone to Sunday school, a strictly Protestant practice in Ireland, and to Mass in a local cinema. To her, the people in Athenry seemed unable to think for themselves, and were, she said, “very much at the mercy of what we would now call superstition.” The eight months she spent in Athenry, and the shell shock of her transplantation, fueled her writing throughout her career.

In her story “Tom,” published in The New Yorker in 1973, Lavin describes an Irish-American family in which the mother’s version of Ireland, a place of serenity, order, and pretty (if delusional) memories, is pitted against the father’s “Ireland.” On a trip home to Roscommon the father, Tom, is shocked to find his former sweetheart is now a shriveled old woman, and the familiar cabins of his childhood, mounds of rubble. The fictional Tom says most of the people he knew had left for the United States long ago.

“ ‘Ah, I knew you were an American, sir,’ an old man tells Tom. ‘Sure, Americans have plenty of money for traveling the world and going anywhere they like.’ ”

Instead of identifying himself to the woman he remembered so fondly, Tom allows her to believe that he is his own son, then abruptly shifts his big car into reverse to drive away without an explanation. “And the black mood that came down on him didn’t lift till we’d crossed the Shannon.”

A curious but integral ingredient in Lavin’s transatlantic DNA is Charles Sumner Bird, the owner of what was in 1920 a successful building products mill in East Walpole. Founded by his grandfather in 1795 as a paper mill, by 1812 it was producing the rag stock used for printing the U.S. dollar.

The younger Bird, who ran unsuccessfully for governor of Massachusetts twice on the Progressive Party ticket, genuinely cared about his employees, introducing 8-hour shifts, a minimum wage, and a workers’ mutual benefit association. Paternalistic as he may appear now (he did not support unions), he nevertheless built recreation halls, reading rooms and parks for his employees and their families, and worked to give them access to good housing.

Theodore Roosevelt wrote to Bird in 1916, “You have been a tower of strength to the men and women of this country who strive for better things in our national life.”

Not only did Tom Lavin work for Bird, but Mary attended the Bird Elementary School, and by 1920, Nora, Tom and Mary were living at the same street address as Bird and his family. How many of Bird’s progressive attitudes filtered into Tom’s conversation at home? Did young Mary, growing up in an atmosphere where the outward principles of social justice were taken for granted, react to the poverty and class distinctions she found in Ireland even more sharply?

While the young writer may have been shaken into being when she first arrived in Athenry, it was in the countryside of County Meath, where she lived for many years when not in Dublin, that Lavin and her writing flourished. She loved the Midlands countryside, but would never have set foot on Bective Bridge if it hadn’t been for the Bird family.

After Mary and her mother moved from Athenry to Dublin, Tom reluctantly left Massachusetts to join them. When Bird’s son, Charlie, a horse racing and hunt enthusiast, decided to buy a country estate not far from Dublin, he hired Tom, whom he knew from East Walpole, to be his agent at Bective House.

The arrangement was fortuitous. Tom and Nora were not happy together, and now they could live apart without disgrace – he at Bective and she in Dublin, while on weekends Mary happily visited her father, who adored his only child. When Tom died, Mary and her husband William Walsh took over as estate agents at Bective House, ultimately buying the nearby Abbey Farm for themselves.

Levenson says Tom’s salary from the Birds allowed Mary to dress well, drive a sports car while a college student, and even travel to the States when her father went there on business for his employer.

Mary became friends with Charlie’s wife, Julia, who introduced her to their neighbor, Edward Plunkett, Lord Dunsany. An author himself, he encouraged the young writer, introduced her to friends in the publishing world, and wrote the preface to her first collection, Tales from Bective Bridge.

Lavin was widowed twice, in 1954 when her husband, lawyer William Walsh, died, leaving her with three young daughters, Valdi, Elizabeth and Caroline, to raise by herself, and again with the 1990 death of Scott, a former Jesuit priest and a friend since college. Having steered through much of her life alone, she was able to infuse her portraits of widows and single women with precision and deep feeling. Far from being exercises in self-pity, these tales celebrate the complex and surprising ways that people navigate their way through grief and loneliness.

American writer Mary Gordon told the Glucksman House audience that critics have often judged female writers like Lavin as too tame, too safe, to be equal contenders in the ring with men.

“Can we ever get over Hemingway’s tiresome boxing metaphors?” Gordon quipped. “Isn’t it possible that the ground of heterosexual male traditional subject matter has been so well-plowed, and well-tilled, and perhaps so carefully over-landscaped now that it is indistinguishable from a golf course?”

Gordon said Lavin “wrote what she wanted and needed to write, even though no one else thought it was important.” The writer rejected the assumption that widows and unattached women, who were not “the conventional objects of male desire, sexual or filial,” should be marginal figures in fiction – or in life. Instead, Lavin found their lives bursting with dangerous possibilities and what Gordon called the “richness of suggestion.”

Such was Lavin’s own experience. In An Arrow in Flight, she recalls with a devilish smirk that, when Scott renounced his religious vows and asked her to marry him, “I half resented it. I’d had a whale of a time as a widow.”

Lavin wrote in bed, early in the morning in her country house in Bective, County Meath, with a breadboard on her knees. She wrote in the National Library in Dublin or in St. Stephen’s Green with Caroline playing at her side. She wrote in the evenings after she made dinner.

“Most male writers have wives to do the housework,” she once told an interviewer, “I don’t.” She recounted writing in “coffee shops, cafes, and bus terminals where I could get some quiet time to myself.” Family vacations happened only when a check, like a Guggenheim Fellowship, arrived in the mail.

But Lavin refused to conform to any neat definitions, even that of a feminist.

“I write as a person,” she said emphatically. “I don’t believe that I am a woman who writes. I am a writer. And I write about people as I see them whether they are men or women. Gender is incidental to me in that sense.”

Still, Greg Londe finds that Lavin’s “stories of widows and of marriage were implicitly deeply political.” Although critics like Elke D’hoker, objecting to the “absence of a clear critique of patriarchy in her work,” have tried to distance Lavin from feminism, Londe argues “she is still absolutely a feminist writer.” Her analysis of the forces that control women’s lives is blatant and powerful, but comes from within her characters and her stories.

“It is never a proclamation,” Londe said, “but rather a chronicle of persistence and suffering.”

Just as Lavin’s writing does not fit a genderized mold, neither will it submit to geographic or national determinism.

Colm Tóibín told the NYU audience that Lavin’s stories do not support the notion that it “is the job of writers to write their nation.” He said Lavin believed “that nations change, but other things don’t, and it is the job of the artist to care more about the other things.”

Although Lavin claimed she couldn’t imagine setting her stories anywhere but in Ireland, Tóibín said she puts the nation, and Catholicism too, into the background, and “removes all the props by which we might read [her characters] easily, refuses to allow us to come to know them by an easy set of signals…They live in a twilight time not of national life but of their own life.

“Mary Lavin was more interested in a character she had invented in all its strangeness and individuality than she was in the wider society; she was more interested in families than politics; she was more interested in the drama around the solitary figure than the drama around Irish history or large questions of identity,” Tóibín continued, all of which “make her work seem so undated.”

In the RTÉ film, Lavin said she never considered becoming a writer until she was jolted by the shock of meeting a woman in her husband’s law office who said she had just had tea with Virginia Woolf (the subject of Lavin’s Ph.D. thesis). Convinced she was wasting her time in academics, Lavin wrote her first story, “Miss Holland,” on the backside pages of that thesis.

Yet Lavin had told Maev Kennedy of The Irish Times 16 years earlier that she began writing “Miss Holland” (“almost absently mindedly” in Kennedy’s words) after returning to Ireland from her first visit back to the United States with her father. “And I couldn’t tell you why I wrote it,” Lavin had confessed at the time.

Maybe the trip back from America as an adult affected her just as deeply as it had when she was a child. After all, “Miss Holland” is the story of a woman, recently torn from a life of comfort and world travel by the death of her father, who attempts to make friends with the inhabitants of the vulgar boarding house where her diminished circumstances have brought her.

Lavin is as interested here in Miss Holland’s self-deception as she is in the vast oceans that can separate people seated at the same dinner table. Still it is only Miss Holland, the stranger, the newcomer, and the woman alone, who is capable of anything so rich and complex as delusion.

Whatever drove Mary Lavin to write, she wrote with an independent woman’s voice and with the sharpened eyes and ears of the new kid in town, and Irish literature is only the richer for that.

—

Daphne Wolf is a PhD candidate in the History and Culture program at Drew University in Madison, NJ. She received her MA in Irish Studies from NYU.

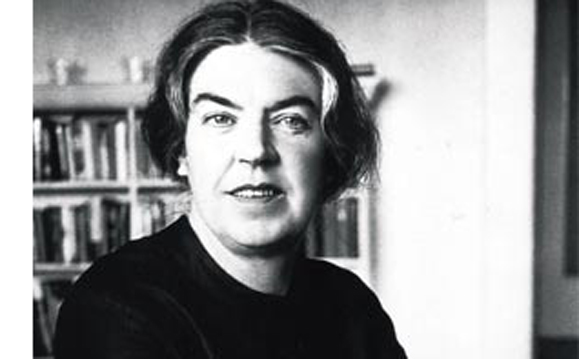

Photos:

Having only ever read one of her stories, I am thoroughly inspired after reading your article to read more. Her life was so interesting! Thank you for a great piece on Mary Lavin.

I discovered Mary Lavin in the past few years and love her work, so subtle and beautiful! Thanks for a great article!