Judy Collins, one of the most influential folk singers of the sixties, and the voice that has been called the voice of the century, still believes that music can heal the world. Interview by Patricia Harty.

It all began with a song.

As a young 14-year-old, Judy Collins heard “The Gypsy Rover” on the radio and it changed the course of her life. She was studying classical piano and had already made her orchestral debut, but the ballad, a tale of a girl who runs off with a dashing stranger, won her heart. She persuaded her father to get her a guitar, broke her piano teacher’s heart, and began the musical journey that would take her out of Colorado and put her on the road to being recognized of one of the greatest singers of our time.

Collins made her first album in 1961, at age 22, won a Grammy Award in 1968 for “Both Sides Now,” made the cover of Life in 1969, and today, more than 40 albums later, at least six of them Gold, she is still recording and playing concerts – up to 100 a year.

Collins has lived in the same New York City upper west side apartment for over 40 years. She shares the space with her husband, Louis Nelson, the artist known for the Korean War memorial in Washington, D.C., whom she met in 1978, and their three cats, Coco (black and white), Tom Wolfe (white), and Rachmaninoff (gray).

The apartment reflects the artistic nature of the occupants: a grand piano in the living room, walls filled with art work, including paintings by Judy’s sister Holly, family photos, Tiffany lamps, Buddhas and other artifacts, and a recording studio. For a number of years now, Collins had been recording her own albums, and a handful of other artists.

Collins is physically lithe and carries herself with the grace of a dancer. She is unhurried, though she’s packing a full schedule. Her body, toned from daily exercise, and her clear skin belie the illnesses of her youth – polio when she was 10, TB in her early 20s, hepatitis and mono, spinal and leg injuries from a fall, and later struggles with an eating disorder, and addictions to alcohol and cigarettes.

Born in Seattle on May 1, 1939, Collins moved with her family to Los Angles at age 10 and shortly thereafter settled in Denver, where her father Charlie Collins hosted a radio show. Blind since the age of 3, Charlie had grown up on a farm in Idaho and had learned to maneuver the world without a cane. Educated at a school for the blind, he was well versed in literature, world affairs, and music, and the five Collins children, three girls and two boys, were brought up knowing that much was expected of them.

At 19, Judy married Peter Taylor and soon gave birth to their son, Clark. To support the family while her husband was in college, Collins sang in bars around Denver. After his graduation, the young couple moved East, where Peter taught English literature at the University of Connecticut, and Judy became popular on the college radio station. But the folk scene was taking off in Greenwich Village in New York City, and this is where Judy was drawn, as were other artists of the day. Judy would meet them all, and record many of their songs – Bob Dylan (while they were guests at Albert Grossman’s house she listened outside Dylan’s bedroom door as he composed “Tambourine Man”), Leonard Cohen (who challenged her to write her own songs), and Joni Mitchell whose song “Both Sides Now” proved a breakthrough hit for Collins, earning her a Grammy Award in 1968.

She also met the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem, who were on the scene when she was offered her first record deal. On that album, A Maid of Constant Sorrow, released in 1961, the 22-year-old Collins would record three Clancy standards, “A Bunch of Thyme,” “Bold Fenian Men” and “The Rising of the Moon.”

As her career was taking off, Collins’ marriage was breaking down. While she was plying her trade and learning her craft she was missing out on her son’s early life. And in the spring of 1962, she met Walter Raim, a guitar player who would be the catalyst for the breakup of her marriage. The affair didn’t last but the ramifications did – divorce and a custody battle for her son, which she lost. It would be several years before she would have custody of Clark again.

Throughout her life, no matter what was happening to her personally, Collins was, and is, a committed social activist. In the 60s and 70s she supported civil rights, and women’s rights, and she traveled South to register black voters. She was in on the founding of the Yippie movement and testified in support of the Chicago Seven during their trial, angering the judge when she sang “Where Have All the Flowers Gone?” on the witness stand.

With the 1966 album In My Life, Collins moved away from straightforward folk music, and has remained untethered to one genre of music. She has a knack of finding a good song and breathing life into it. Her 1968 recording of “Amazing Grace” brought the 18th-century hymn back into the present day (it was top of the charts both in the U.K. and U.S.), and it has remained part of our cultural consciousness. Stephen Sondheim’s “Send In the Clowns” was also a huge hit. She appeared with the Boston Pops Orchestra and on the Muppet Show, and made many appearances on Sesame Street. She even took a turn on the New York stage, appearing with Stacy Keach (whom she lived with for a time) in the 1969 revival of Peer Gynt.

Collins also produced and co-directed an award-winning documentary on her former piano coach Antonia Brico (1974). And she has written several books based on her life, in which she tackles difficult issues such as the suicide of her son Clark in 1992, and her own battle with alcoholism. Her books include Sanity and Grace: A Journey of Suicide Survival and Strength (2006), and Sweet Judy Blue Eyes: My Life in Music (2011). The latter title comes from the song written about her by Stephen Stills. (The two met in 1967 and had a two-year passionate affair.)

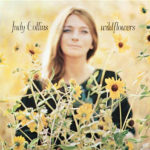

Today, Collins continues to pursue her creative passions. She created her own label, Wildflower Records, in 2000 to record her own music and support the work of other artists. She writes songs and books and continues to perform. When we met at her apartment in late April, she had recently had a guest spot on the TV series Girls (she said it gave her street cred with her nieces and nephews) and was preparing for a June 8 concert at the Town Hall, New York. She was also planning a trip to the U.K. and Ireland, where she will record a concert for PBS, and where she will be inducted into the Irish America Hall of Fame in New Ross on June 21.

Was music part of your childhood?

Music was very much a part of my childhood. I listened to all Rodgers and Hart and Great American Songbook [recordings] because my father played them on air. He was also a musician and sang. I played Bach and Beethoven and Debussy and Mozart, and I sang the opera arias, but I also listened to pop music – the stuff that was on the radio – “Earth Angel” and so on, when I was in high school. So I was exposed to a lot of different kinds of music before I started singing folk music.

Was your father disappointed when you gave up classical piano?

Well, he only rented the guitar that he got me so maybe he was optimistically hopeful that it wouldn’t last, but he loved the folk songs and Irish songs.

Tell me about him.

He was very musical, very dramatic, very handsome, articulate, well read – he read everything in Braille. We loved to brag that our father could read in the dark. We were raised on great literature and great music and we had a very liberal education. He was also very radical in his politics. We wouldn’t call it radical now, he was actually a humanist and a FDR Democrat and very outspoken on the radio. He’d talk about anything and everything. He read Dylan Thomas. He’d read Emerson, and he’d sing, and then he’d talk about Joe McCarthy and he’d talk about the war in Vietnam. Not in appreciative ways, either one. And he was really a very, very interesting man altogether. He also drank a lot. I got that Irish bug from him certainly.

Do you know from whence the Collins hail?

My Irish relatives came into Virginia probably around 1886, I don’t know for sure – they didn’t keep records. Now, the English side who came in through Canada are unbelievably well-documented, but the Collinses didn’t keep records. But I’m sure that’s where the music comes from. We celebrate the Irish all the time in our family. My father loved Irish music and used to sing “Danny Boy” and the “Kerry Dances,” which I will sing on my PBS special from Ireland. It [“Kerry Dances”] has a special place in the family. My nephews and nieces sing it, and my granddaughter.

How well did you know the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem?

I adored the Clancys and I sang with them a number of times. They were recording already for Electra and the first television show I did, they were on it. It was that 1961 television show that got me my record label because the guy who ran the label was there and he said, “Oh, you have to record for me.”

Later I stayed in touch with Tommy Makem and recorded a television show with him before he died.

You had a big hit with Leonard Cohen’s song “Suzanne.” Can you tell me about your relationship?

Leonard was the one who started me writing my own songs. It was 1966, and I had recorded several of his songs and he said, “How come you’re not writing any of your own songs since you’ve recorded all mine?”

I saw him the other night and he said, “I owe you so much” and I said, “No, the debt is mine” because if he’d never asked me why I wasn’t writing songs, I never would have.

And didn’t you push him to perform his own work?

Yes. I confess. I did get him to perform. Back then he’d always said, “I can’t sing. I can’t play the guitar. I can’t perform these songs in public.” But I knew he had a mesmerizing voice. So, I was doing a benefit for WBAI, the radio station, and I said, “Why don’t you come down and sing ‘Suzanne,’ it will drive the crowd crazy. My recording of the song was up on the charts for 38 weeks at the time. And he said, “No, I can’t do it,” and I said, “Come on. It’ll be fun.” I forced him to do it. He walked out on the stage and started to sing – it was a big audience, about two thousand people – then he stopped in the middle and walked off. He said, “I can’t go on.” and I said, “You have to go on. I’ll go up and sing it with you, but you do not leave the stage and not go back on. It’s really bad.” So he went back on stage and we finished singing “Suzanne” together and the audience went crazy.

You also had a hit with Joni Mitchell’s “Both Sides Now” before Joni was well known. Can you tell me about artists’ rights and royalties: How does it work?

Joni would get her standard [writer’s] royalty and I would get my performer’s payment if the record was selling in the stores. However – and this is a big ball of contention, something that’s been going on for 90 or a hundred years – no performer gets paid for radio play. People began to think, in some parts of their ill-educated brain, that the radio stations were doing us a favor by playing our music. When I went to Washington the first time to protest piracy, someone asked, “How do you feel about performer royalties?” The question went straight over my head. I said, “I don’t really know what you’re talking about.” He said, “Well, you’re not getting paid for your radio play.” So then, of course, the dawn begins to break. This is almost the only country in the free world where that’s true. Nearly everywhere else, an artist gets paid for their performance whether they wrote the song or not.

Do you miss the way recordings were made – the sound of the needle on vinyl?

No, not at all. When I first started recording music at home we had a wired tape recorder and these bundles of wire that would get stuck and you couldn’t align. It’s strange how everything has changed, but I don’t miss any of it. I have my own studio here in the house, which I’ve had since 1994, and I’ve done a lot of albums here, but I can also go and record a concert at the Metropolitan Museum and have it be transferred as is, without any other work on my part. So, the sound that we get in theaters and in concerts is excellent and the equipment keeps getting better.

How do you keep your voice in such good shape?

I studied for years with a great teacher – 32 years. I went to him in 1965, I was desperate because I was losing my voice and a guitar player for Harry Belafonte, a guy named Ray Boguslav said, “You must go and see Max Margulis immediately.” And I did, and I persuaded him to take me on as a student. He was very eccentric. He had very few students.

Did his method involve vocal exercises?

No. It’s about clarity and phrasing. Of course, I’ve done this for a long time now, so I know how to warm up and I know how to be clear and to phrase. When Max was on his deathbed he said to me: “I don’t want you to worry. Just remember the phrasing and the clarity and you will be fine.”

His philosophy was that there was one voice: singer, speaker – it was all one instrument and you could either wreck it or you could use it until you fell over.

And it seems like you are going to keep going until you fall over. What drives you to keep performing?

It’s very compelling what I do. I think I have a compelling life. I write books, I write songs, I record, I make CDs. I travel. I tour. I think it’s important to keep working. I would never retire. Never, ever. Unless I am pushed off the stage or a cliff, I don’t think I will be retiring.

Do you get nervous before you perform?

I never suffer performance anxiety.

Because you do yoga and meditate?

I meditate for its own sake. And I do something called ‘self-realization.’ It involves a set of yoga practices and a set of breathing situations in which there’s a mantra and a lot of prayers and so on. It takes about a half hour and I try to do it twice a day, wherever I am. You don’t have to have special shoes for it. You don’t have to be in a special place to do it. You just do it – if you’re in the plane, if you’re in the car, if you’re sitting doing your make-up. It’s very portable.

Do you watch what you eat?

Yes. I had an eating disorder for years. It really kicked in when I gave up smoking. I was always on diets. Everything was very extreme and I never gained a lot of weight because I was always exercising. I discovered exercise very early on, and for me, that’s the big secret. It’s endorphins. If I’m exercising every day, I’m fine. I really am. If I’m not, I’m in trouble, but I learned that very early on, even in the dark days of my drinking. It’s probably what kept me alive.

Do you think there’s a genetic component to alcoholism and depression?

There’s definitely a genetic component and it has to do with things that run in families – depression, chemical imbalance. As I said, I inherited the “Irish bug” from my father, who liked to drink. Although I looked good on paper – I had hit records, and concerts all over the world, I couldn’t work most of 1977. My life was a total shambles. I couldn’t sing. I had lost my voice. I am quite sure it was the booze. I had a hemangioma on my vocal cord. My doctor said, “If you do this [operation] you have a chance but if you don’t do it, you have no chance and you’ll never sing again.” That was my choice and I had the operation and it worked. Then I stopped drinking. I finally went into treatment and got the help that I needed in 1978.

Wasn’t it around this time that you met your husband, Louis Nelson?

We had met four days before I went into treatment and in fact, the day that we met is the day that’s on the wedding rings that we both wear. I talked to him a lot on the phone when I was in treatment and then I came back and we had our first date in July. So, I was actually nearly three months sober by then. It just seemed to be the right fit. We’ve been together ever since. Not bad for a hippie.

How did you get through that dark period following your son’s suicide?

People reached out to me and I had a support system and people that I could call, and when I went on the road my family came out with me. My mother came and traveled with me, and my sister Holly. I got through it with a lot of help, and when I started to feel a little stronger, I realized that I had to do some kind of active participation in suicide prevention. So I got involved here in New York, but then I found out that [the meetings] were run by the drug companies, and financed by the drug companies, so I backed off of that and instead I have done some speaking out on the issue. I was invited to speak in Belfast on radio about this, and so many people called in. It’s a terrible problem. I was even brought up to Harvard to talk to their medical community about it. I talk about it maybe four or five times a year. I do either a fundraiser or a dinner or something for suicide prevention and I speak to groups in hospital environments and in educational and mental health environments.

There was no way for me to deal with it unless I talked about it. I had to go to lots of survivor group meetings and I had to think about who was doing what about it.

The taboo about suicide is huge. It’s something that the church used to punish people for by not allowing suicides to be buried in hallowed grounds.

As the 50th anniversary of JFK’s death nears, what are your memories?

I had just sung for him in the spring, a few months before his death. I was on my way to Washington, D.C. to visit my friend, the photographer Rowland Scherman. I got off the bus at La Guardia and I heard that President Kennedy had been shot, and when the plane landed in Washington, I found out that he was dead. I couldn’t imagine that someone with the force of his personality and charisma could be gone. And five years later, in 1968, Rowland was on the Robert Kennedy team during the run up to the election. He’d gotten closer to the Kennedy family and they liked his work a lot, and he was in that group when RFK was shot at the Ambassador Hotel. Three days later Life sent him to take pictures of me. Isn’t that strange? I’d forgotten about it, until this morning when I was writing an introduction to a book of Rowland’s photos. We did take pictures and made great music and that was the only thing to do. It was such a tragedy. We thought about it and said, “Let’s go ahead with the sessions” because what else would we do?

Do you still believe music will heal the world?

Well, art and music are the only thing we’ve got. They have always been the only thing we’ve got, because we always have problems. We always have murder. We always have greed. We always have people who are nuts and there’s always something awful happening somewhere. So, you have to have art. Every culture in the world has realized that art is the thing, that art is primary.

I did a concert at the Metropolitan Museum, and one day I was having lunch with Emily Rafferty, the museum president. We were talking about the power of art and how people need it – no matter who you are and where you are – to deal with just being on the planet. Emily said that the day after 9/11, [Mayor] Giuliani, in one of his more intelligent and gracious moments, called her and said, “You must open the museum.” She said, “How can I – there are no phones, everything is down.” Somehow, through word of mouth, and running around town and finding the staff, they opened. She said thousands of people just streamed into the museum in the following days because in the museum, they could see that people had lived through horrors before and survived. It was a touching thing.

Can you talk about “Kingdom Come,” your own anthem to 9/11, and how it came about?

In the aftermath of 9/11, Louis and I were invited to one of those parties with all the firefighters – it was a big effort of trying to give them something that was pleasant, a musical evening. Kevin Bacon was there, as were other artists. One of the firefighters said to me, “See this tattoo behind my ear here and on my neck?” It said “343,” the number of firemen that died on 9/11.

That image really stuck with me, and I would talk about it a lot, until finally my husband said, “Why don’t you write a song about it?” We were up in the country at the time so I found a way to do it on the guitar, and when I thought I had it, I sang it in a number of firehouses for the crews because I wanted to be sure I got it right. I’ve met some incredible firefighters. One of them, Captain Jim McGrath, lost 91 friends that day. Can you imagine? Your whole working population from your firehouse and others, just

gone.

I think artists will continue to write about it, and think about it a lot, and since this new terrorist attack in Boston, which is what it was, I think there’s a renewed feeling of what a new and terrible world it is in a lot of ways.

There were so many protests in the 60s and 70s. Do you think today’s young people are apathetic?

I don’t think they’re apathetic but I do think that they need leadership. I think they can be galvanized by issues. They certainly are active in a lot of ways. I had a conversation with Pete Seeger around his birthday and I said, “How are you feeling about the world?” And he said, “You know, I have never been so optimistic.” He said, “Think about all the things that people are doing all over this country and all over the world that are positive. Little groups here and there, but they are everywhere and they are all working on something. They’re doing victory gardens to try to get Monsanto down off the perch, or they’re trying to figure out how we get the immigration bill passed. I mean, I think the country is being utterly ignored by the Congress – I think it’s so disgusting that they couldn’t pass something on gun control. It’s very depressing, but something will turn around and change. It’s got to.

What do you have on your iPod?

Oh, gosh. So much – everybody from Adele to Shawn Colvin, Amy Speace to the Irish Rovers. I have all kinds of things and I’ve just been listening to a lot of a singer/songwriter whose name is Hugh Prestwood. I recorded six of his songs on different albums: He was big in the 80s and I rediscovered him. He sent me a whole bunch of new material and I’m just absolutely crazy about it. I’m going to put him on my label.

What’s your favorite song that you’ve written?

It always changes. Right now, the most important one to me is one I wrote about my mother, called “In the Twilight,” which is on my last album.

She passed away at 94, in December 2010. She was quite a lady. She had a kind of, I want to say stillness and ability to go through what was demanded of her that was really quite remarkable, and she was a great cook and a great housekeeper and she had a great sense of humor. She was – we called her the original party girl. I think of her putting on her Chanel perfume and her pretty clothes and she was off to the races. She’d dance all night.

Do you believe in an afterlife?

Oh, that’s interesting. Do I? I certainly believe in God. I certainly believe in other realms of experience, by all means, and there was the discussion we were having the other day about psychics and the things that happen to us in meditation. How could you not be a believer in something other than what’s going on here? It’s pretty pathetic if this is it.

Thank you, Judy Collins.

What a wonderful article! I have always loved Judy Collins. I have seen her many times in person over the years. I hope to see her again before I leave this world. She is an awesome person and you have captured her perfectly is this amazing article. Good job!!!

Great article / interview. I heard Judy sing live last time she was in Dublin Ireland. I have loved her music since the early 70’s. Her honesty in inspirational; her energy, contagious and her music, enthralling. Long may it continue. Great article. Congrats to Patricia and Judy.

I can remember sunbathing on the front lawn listening to Judy Collins and Joni Mitchell records on our huge old record player that I would lug outside on sunny days. My mother would come out screaming that I should be doing something useful. I would retaliate by sing to her the Rod Stewart hit about ‘the big fat mamma trying to break me…’

I have rediscovered Judy and Joni just lately. They are both talented and wonderful to see them both going strong, Judy singing even better at 74! … and Joni chain smoking still, but still looking beautiful… I was so in love with those girls! And now that I am at that age I can appreciate how extraordinarily intelligent and gifted they both are… loved reading this article and so sad to hear about her son. I could relate to that as my brother committed suicide when he was 16 by throwing himself out of an upstairs window. Something like that affects you for the rest of your life… I love Judy’s version of ‘Someday Soon.’ It fills my heart. What a beautiful song

Judy:

together at last. the two of us of the same generation, me 1940 fo you have me by a year. you have a year on me. I also count my self as a

Seattle native. I have been a fan for a long time and only now have a

request/invite for you. I am one of the receptionists at the Mt Si Senior Center up here in North Bend. We serve twen’ 30 and 50 seniors for noon lunch. if you could put a brief visit in it would be a real thrill for me and the senior citizens we serve.

anyway I welcome this brief opportunity to come close to talking to you. regards,

Bob Edwards

Dear Irish American – first, I read the Bobby Sands and then I read this article – I’m so grateful to the magazine for revealing some of my life – it’s a privilege and my performing life is a gift and a privilege as well. Thank you to everybody who supports me goes out to my concerts. Buys my albums, and makes my life Complete because I can continue to create as long as I live —one hopes -I just turned 85 and I’m going strong so Irish American has helped me all along the way thank you thank you thank you. Judy Collins