A search through Dermot McEvoy’s family history revealed an eye-opening secret. Here’s what he discovered, plus a guide to researching your own Irish ancestors. (This article has been updated since its original publication to reflect the most recent re-location of the General Registry Office.)

Mary Josephine Kavanagh was born in Dublin on March 18, 1907.

She was my mother, or so I thought, until I discovered that Mary Josephine Kavanagh died three months after she was born on June 24, 1907.

Who, exactly, was my mother, the woman using the name Mary Josephine Kavanagh?

She died in 1989 so I couldn’t ask her.

The mystery began when I discovered the Irish Census of 1911 online and found my grandparents, Joseph Kavanagh and Rosanna (née Conway) Kavanagh. My grandparents married in 1900 and the census showed that they had six children, five of whom were alive in 1911. A search for my maternal great-grandmother, Bridget O’Brien Kavanagh, showed that she died in 1898. The Glasnevin Trust website showed that she was buried in Glasnevin Cemetery – Ireland’s largest, situated on Finglas Road, Dublin. The search also showed that an infant, Mary Josephine Kavanagh, was buried in the same family plot.

I returned to the Census of 1911 and found “Mary,” aged three. According to all official documentation, Mary Josephine, my mother, would have been four in 1911.

Back at the Glasnevin General Research Room Office on Lower Abbey Street in Dublin, I went to the 1908 Births Book and cross-referenced Kavanagh with my grandmother’s maiden name, Conway. The records showed that on May 18, 1908 a girl, “Bridget,” was born to my grandmother at the Rotunda Hospital.

Could this “Bridget” be my mother, known to all as “Mary”?

As best I can discern, my mother, Bridget Kavanagh, known as Mary in the 1911 Census, innocently took on her dead sister’s identity. Losing a child in those years was not uncommon. If my mother knew about Mary Josephine she certainly never mentioned it.

My grandmother died of tuberculosis in 1915 and my mother was put in an orphanage in Sandymount while her younger brother, Dick, was placed in a separate orphanage for boys. My grandfather kept the two older boys, Joseph and Frank, at home. With the advent of the War of Independence my grandfather and his two sons were involved in the IRA, with the two boys going “on the run” in the Dublin Mountains.

One of my mother’s last memories of her father was being taken by him to view the body of the Irish revolutionary leader Michael Collins as it lay in state in Dublin’s City Hall in 1922.

My grandfather died in January 1924 from injuries he received at the hands of the Black and Tans, the notorious auxiliary police brought in to suppress the rebellion. Soon afterwards, my mother escaped the orphanage and went to work in a tobacconist shop in Bray, a seaside town not far from Dublin, where she began a lifelong addiction to her beloved cigarettes. Later she worked as a servant for various Anglo-Irish families before settling in the Dublin suburb of Foxrock, as a cook for a Mrs. Darley, whose neighbors were the Becketts – the family of the writer Samuel Beckett.

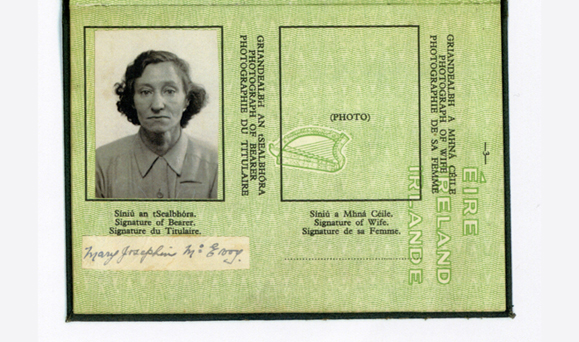

My mother met and married my father Dermot McEvoy, who was a Land Stewart at a farm in Seapoint, Donabate, Co. Dublin. He immigrated to New York in 1953 and found work as a building superintendent and a plumber in Greenwich Village. My mother and I followed in 1954. Perhaps it was at this time that my mother applied for her birth certificate and was mistakenly given her dead sister’s. In any case, she became Mary Josephine Kavanagh, born in 1907. A fact that is stated on both her Irish and her American passport.

Scampering around the Internet I found a birth notation for a Bridget Mary Kavanagh of North Dublin in the spring of 1908 on the Mormon website FamilySearch.org. Unfortunately, no parents were listed so it’s impossible to know if this was my mother. But it might show that “Mary” was part of her name from the time of her baptism, making the transition from “Bridget” to “Mary” within the family more natural.

I look forward to finding my mother’s baptismal certificate, and the only place to do that is in person at the National Library in Dublin, where the microfiche should provide the final piece to my family puzzle.

My mother died on May 2, 1989 in New York City. She is buried in the family plot in Glasnevin Cemetery, and her name is recorded on the same headstone as that of her mother, father, and brothers Charlie and Joseph. The inscription reads “Mary Kavanagh: March 18, 1907 – May 2, 1989.” The headstone was erected by my uncle Dick in 1961, on his only trip back to Ireland. Dick is buried in the Bronx.

I hope one day to add the name Mary Josephine Kavanagh to the headstone as a tribute to the infant sister whose name my mother carried throughout her life.

Irish Genealogy Tools

• Step One: The Census

The National Archives of Ireland provide many important services – all of them free. Foremost among these services are the Censuses of 1901 and 1911, the last surviving censuses administered by the British government. All counties are included. You can access both censuses at www.census.nationalarchives.ie.

The information provided includes names, addresses, occupations, religion and literacy (“can read and write”), whether Gaelic (referred to as “Irish” in Ireland) is spoken, and number of children born and number of children living. The form is signed by the head of the household, perhaps giving you a first look at the penmanship of your great-great-grandfather.

• Step Two: Parish Records

Another invaluable service provided by the National Archives is the Parish Records, with free access available at www.irishgenealogy.ie.

Parish records include baptismal information and, to a lesser extent, marriage and death information. Currently available are Carlow (COI), Cork and Ross (RC), Dublin (COI, PRESBY, RC) and Kerry (COI, RC). Updates are ongoing. It is also possible, in certain circumstances, to print out the actual page about the baptism or marriage.

The National Library of Ireland located in Dublin at 2/3 Kildare Street, just down the street from the Shelbourne Hotel, offers microfilm copies of Catholic Parish Registers and the Tithe Applotment Books, online access to Griffiths Primary Valuation of Property and many printed resources such as newspapers and trade directories.

The Genealogy Advisory Service is available free of charge to all personal callers to the Library who wish to research their family history in Ireland. (Check website for seasonal hours and other genealogical services.)

Another excellent, free service, provided by the Mormon Church, is called Family Search (www.familysearch.org), which claims to be the world’s largest genealogy organization. It is through this service that I found the birth and death dates of many of my relatives, which I later turned into birth/death/marriages certificates in Dublin.

• Step Three: Cemeteries

If you know where your people are buried, cemeteries contain a wealth of family information, specifically, birth and death dates on headstones. More detailed information can often be found in records located in cemetery offices.

In Dublin, the newly built Glasnevin Trust Museum offers a fascinating look at Ireland’s foremost cemetery (take a taxi or the #9 or #83 bus from the city center – a fifteen minute ride – and ask the driver to let you out near the cemetery). Tours commence at 2:30 p.m. daily. Charge is €6 (approximately $8.50). The tour includes entrance into Daniel O’Connell’s tomb (it is considered “lucky” to touch his coffin), a visit to the appropriately named “Republican Plot” where many famous Irish revolutionaries are buried, plus visits to the graves of patriots Eamon de Valera and Michael Collins.

But the biggest service offered by the Glasnevin Trust is its fantastic website (glasnevintrust.ie), which gives access to the names of almost all who have been buried at Glasnevin from 1828 to the present (over a million people). A preliminary search is free and a detailed search of the grave is available for approximately $4.25 – $11.25). This service is invaluable because it provides a list of everyone in a particular grave. Often, names were not recorded on the headstone.

• Step Four: General Register Office Research Room*

The bad news is that GRO Research Room is not Internet friendly (only rudimentary information is available at www.groireland.ie/research.htm). The good news is that if you go there in person they have all the information you’ll ever need.

How to find it: The General Register Office Research Room of the Department of Social and Family Affairs is located in Dublin at Block 7, Irish Life Shopping Mall, 3rd floor, Lower Abbey Street (it can be entered through Northumberland Square). This is at the end of Abbey Street, near the Customs House and about two blocks east of the Abbey Theatre. Finding this place is the most difficult obstacle. Hours are daily, 9:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. Once inside, you will have access to all births/deaths/marriages in Ireland from 1864 onward (and non-Catholic marriages from 1845). It is approximately $28 for a day-long search of all the indexes; a particular search is €2. Once you find your relative there is a €4 certificate photocopy fee with a maximum of 5 photocopies per person per day. A day of fruitful research will run you a maximum of $56. The staff is extremely professional and helpful. Instant genealogical gratification!

• Step Five: Irish in the British Military and the Guinness Brewery

Many Dublin Irish joined the military from the 19th century through the Great War. My great-uncle Charlie Conway (my maternal grandmother’s brother) was one of these men. He served twenty years in the British military and he also worked at the Guinness Brewery as a policeman for thirty years, and is a member of Guinness’ Honour Roll of Employees who served in His Majesty’s Naval, Military and Air Forces, 1914 – 1918.

The Royal Dublin Fusiliers Association (www.greatwar.ie) is a valuable resource service run by Seán Connolly on the Royal Dublin Fusiliers. The British Army WWI regiment was one of the five Irish regiments disbanded by the British following the signing of the treaty in December 1921, which created the Irish Free State.

Another source of information is the Guinness Archive. If you had a relative who was an employee of Guinness it is possible to make an appointment to view their employment record. (I found that my great Uncle Charlie won first prize for keeping his uniform in good order during 1904. On the other hand, on June 10, 1910 he was “found asleep when on duty at the basement stairs of Market Street Storehouse,” and “severely reprimanded by Mr. Phillips.”) The Guinness Archives are located at the Guinness Storehouse – which, ironically, was Uncle Charlie’s beat – off James’ Street, the same building where the Guinness tour is conducted.

Dermot McEvoy is the author of several books. He is currently working on The 13th Apostle: A Novel of a Dublin Family (Skyhorse Publishing), which is loosely based on his mother’s family.

*UPDATE: The General Registry Office has moved from Lower Abbey Street. It is now in Werburgh Street, near Christ Church Cathedral. It is hidden down an alley. Here is how to find it:

Across from Christ Church, at the corner of Werburgh Street, is the Lord Edward pub/restaurant. Next to the Lord Edward is Leo Burdock’s Fish & Chips. Cross the street here and you are in front of St. Werburgh’s Church of Ireland, where Lord Edward Fitzgerald is buried. To the right of the Church is the Parish Office. To the right of the Parish Office is an alley. At the end of the alley is a sign declaring “Oifig an And-Chlaraitheora”–the General Registry Office. Congratulations, you have found it!

Hi Dermot, I found your story of your mother very interesting. I had a similar story with my mother.

She immigrated to Canada from Dublin Ireland in the 1950s with someone elses passport.

I realized this in 2004 when I started doing genealogy.

Because she was fostered in Ireland, she was never able to find her original birth certificate so she chose the one that closely fit her date of birth and name.

In 2004,after much searching I was able to find her baptismal record at the Pro Cathdral in Dublin. There was no corresponding birth certificate to match. To this day, I can’t find her original cert.

I don’t think our stories are unique.

By the way, my father’s family all worked at Guinness and the archivist gave me copies of all their work histories, illness, childrens’ ages, pension info etc. It helped me enormously with my genealogy.

Thanks for posting your story!

Hi from Dublin,

Did you find any more information on your Mam?

Kaye.