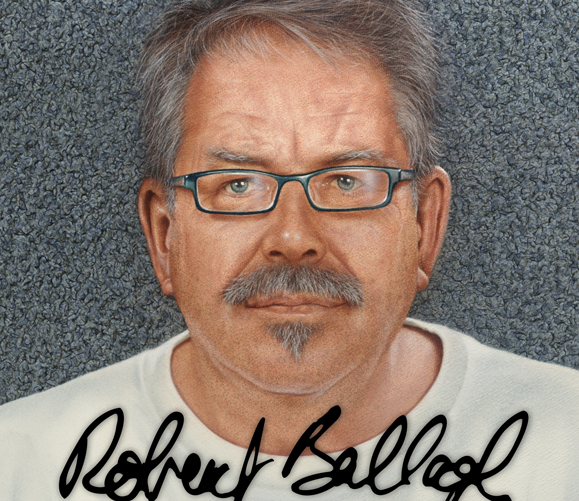

Robert Ballagh is one of Ireland’s most distinguished artists. Born in Dublin in 1943, he is represented in many important collections including the National Gallery of Ireland and the Irish Museum of Modern Art. Besides painting, has also produced book covers, posters, limited editions, over 70 stamps for the Irish postal service and the last Irish bank notes produced by the Central Bank of Ireland.

In 1985 he was commissioned by the Gate Theatre, Dublin to design Barry McGovern’s acclaimed one-man Beckett piece I’ll Go On, and since then he has designed many successful theatrical shows, including the imagery and set design for the dance phenomenon Riverdance.

Ballagh has chaired the national executive of the Irish National Congress, a non-party political organization working for peace, unity and justice in Ireland, and is currently president of the Ireland Institute, a center for historical and cultural studies. He is also a member of Aosdána, a self-governing trust of Ireland’s most distinguished artists, and is a fellow of the World Academy of Art and Science.

Fellow artist Brian O’Doherty, speaking at the American Irish Historical Society New York launch of Robert Ballagh: Citizen Artist by Ciaran Carty, said, “We know that the arts attract their quota of poseurs and esthetes. Bobby – and this was shared by his wonderful late wife, Betty – detests pretentiousness and artistic snobbery. His realism is a rebuke to all kinds of fakery social and otherwise. That doesn’t make you popular with the pretentious. He has lived a simple life as husband and father. If you want to know how a Dublin life – Ballagh’s life – was/is lived, look at the marvelous paintings of his domestic life.”

Betty, the subject of many of Ballagh’s paintings, and the mother of his two children, Rachel and Bruce, passed away suddenly in 2011. Robert has been very critical of the Irish health service and the treatment she received.

Here are excerpts from a conversation with Robert Ballagh on a visit to New York.

Who were your early influences?

Largely, but not exclusively, American pop artists such as Roy Lichtenstein and Andy Warhol. I always loved that kind of American cool from the movies, and pop art carried that cool irony, and that’s what got me going. I didn’t train as an artist. I trained as an architect until I gave up being a student and became a musician. When I decided to relabel myself an artist, the pop art form seemed simple and something that I could do. I rapidly became Ireland’s Number 1 pop artist, which wasn’t hard as I was the only Irish artist doing that kind of work.

Yet you resisted being pigeonholed as an artist.

One of the dark sides of American art is consumer branding. Lichtenstein, in spite of his brilliance, was trapped in this comic-book style for the rest of his life.

So I very slowly began to try and improve and do work that’s more in line with the classic artists that I admired – Vermeer, Holbein, Velazquez – and after 45 years I’ve ended up painting as I always wanted to paint.

Greatest achievement?

A commissioned portrait that I just finished. I think that if you ask any artist they will say the last thing they did.

I can now concentrate mostly on painting. And I actually think I’m getting quite good at it. It’s an accumulation over the years. My son, looking at my latest work, said, “Isn’t it tragic you are just getting good at it and it’s almost over.” Meaning that I will be 70 next September.

For years you were known as the stamp-and-money man.

I did 70 stamps for the post office and that gave me some profile in that area, and later I was commissioned for the bank notes in Ireland. It was the one area of my achievement that the people in the U.S. knew about, and I’d be introduced as the guy who did the Irish money. Unfortunately I can no longer pull out samples of my work. For a long time that’s what kept me going.

Theater break?

In 1985 Michael Colgan employed me to design a set for the Gate Theatre. I knew nothing about set design but sometimes not knowing anything is a plus. It was for a Beckett one-man show and it went on to win awards, and suddenly I had a career in the theater. I went on to work on the Riverdance set for Moya Doherty and John McColgan.

The difference between working in theater and working on your own?

Theater is intrinsically cooperative. What you do is just one part of the process and I was fortunate to work with the very best people.

Hero, dead or alive?

Noel Browne (d. 1997). He was born into grinding poverty. The family was evicted after the father contacted TB and died. His mother and several of his siblings also died of TB. Yet his is an extraordinary story of how he overcame circumstances to become a doctor and politician and help eradicate TB, which was a curse in Ireland. He went on to try and establish a health service that would help mothers and children, which provoked savage attacks on him, and he resigned as Minister of Health. During the ’80s I had been commissioned to paint many of the Irish establishment, but not Noel Browne. By that time I had a few dollars so I commissioned myself to paint him. He had a certain reticence but we met up and he invited me to come to Connemara where he and his wife, Phyllis, had a cottage.

It was an extraordinary experience for me. We took many walks along the sea-shore discussing politics and life. What struck me at the time was that there wasn’t a trace of bitterness for the way he was treated. I would say the only negative emotion he expressed was disappointment.

Modern day person of interest?

Doctor James D. Watson, the scientist who unraveled the structure of DNA. I was commissioned to paint his portrait, which now hangs in the Department of Genetics at Trinity College. When I asked him what he thought of the finished painting, he said, “It’s a marvelous portrait and the start of a marvelous friendship,” and it has been. He recently commissioned me to paint one of the benefactors of his Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. I feel like I’ve done an exam after a few hours with Jim — he doesn’t do small talk. I always enjoy being in his company. I find it very exciting. We talk about everything from the economy to the presidential election and he always has fresh ideas – ideas coming from a different direction.

Your typical day?

I get up at about seven or eight and go to the studio and get back from the studio at around six. My work is a slog. Someone joked that great work is 10 percent inspiration and 90 percent perspiration.

Your idea of a perfect day?

I had a few perfect days on this visit to New York. I walked the Highline and the weather was gorgeous. I had lunch at The River Cafe in Brooklyn with friends and afterwards the sun was shining and I said, ‘I’m walking the bridge going back,’ so I did. I had never done that before.

Something you do on every visit to New York?

I always go to the Frick when I come here to see the work done by the old masters. I look at Holbein’s painting from 500 years ago of Thomas More that’s right beside the fireplace. I take off my glasses because my vision is good up to six or nine inches and I get as close to the painting as I can, and every time I go the security guard will come up and say, “Please sir, move away.” I look at that painting and I think, I’ve been at it for 45 years and I’m not half as good as that.

Your pet peeve?

Cell phones. You’re with people and having a great conversation and the next thing they are talking on the phone. It’s the equivalent of being at a party and the person you are talking to says ‘excuse me, there is someone more interesting over there.’ Everything about human relations have developed an etiquette around it and there hasn’t been time to develop an etiquette around the mobile phone.

On embracing technology.

I don’t have a computer or a mobile phone. It might sound pretentious but I don’t have enough time to learn how to use that stuff. I have to give the rest of my time to my own craft and to trying to get better at what I do. But it makes you an outsider – people get annoyed when they ask for my cell phone number and I say I don’t have one.

I miss the way things used to be – the amount of conversation that I struck up on the subway over the years – no one talks to anyone any more, they are all plugged into something.

On growing up.

My father was Presbyterian and my mother Roman Catholic, and because of the Ne Temere Decree I was brought up Catholic. I remember a priest saying that only Catholics could enter heaven and I wanted to say, “What about my Da?” We never talked about politics in the house because my mother’s parents ended up on opposite sides in the civil war and the families didn’t talk for 10 years after the war. So my mother would not talk about politics. Who you voted for was your own business and no one else’s.

Earliest memory?

I don’t think I’ve ever discussed this before. My mother was a very neat person but for some reason she hated straight hair so when I was small she permed my hair. I remember going out to play and she would put clips in my hair.

Hidden talent?

I was a professional musician but I retired in 1966 and haven’t lifted a bass guitar since. But there’s an element of celebrity in the fact that when I retired I sold my guitar to a young fellow called Phil Lynnot who was just taking up the bass, and if you check all the iconic photos of Phil he’s playing my bass. I might not have become a famous musician but my instrument did.

What’s with the earring?

When Betty died and we were cleaning out I found these earrings that I’d given her of Kokopelli. I bought her diamond earrings and they stayed in the box, but Kokopelli, which I found in a Native American store in Oklahoma years ago, never left her ears. So I thought that as a personal memorial it would be interesting to wear one of the earrings, which involved me having to go into a tattoo shop to get my ear pierced, which was a kind of interesting experience. Kokopelli is the god of fertility and agriculture so he’s quite important, mostly to the Hopi Indians but the Aztec and the Mayans have a similar guy so it’s obviously something that is part of the Americas.

I discussed doing a Riverdance show with Native Americans but it never came to anything.

Working on at the moment?

A stained-glass window for Quinnipiac – have to get stuck into that when I get home. Then there’s also a Connecticut bloke who wants to do a 1916 Memorial, so they want me to do something.

I’m also doing a big project at home, which is really interesting. Next year is the centenary of the 1913 Lockout. SIPTU, once the Irish transport and general workers union, the union that was locked out, commissioned me and another artist, Cathy Henderson, to design a tapestry to be executed by voluntary groups and individuals. Which in theory is great but in practice means working with about 200 people with no experience and wide range of skills.

The legacy of Section 31?

Section 31 [members of Sinn Féin members were banned from radio and TV under the broadcasting ban, 1971 to 1993, as were rebel songs] was culturally and psychologically damaging. When a friend of mine, an actor from Belfast, was auditioning and he was told, “We are not casting Northern actors – we find the Northern accent very threatening,” I just felt it was time to do something about it. I was involved in a project to commemorate the 75th anniversary of the Easter Rising in 1991, a small program of poetry and song, which we wanted to do outside the GPO [General Post Office which was central to the Rising]. We got a flat bed lorry and it was my job to get 100 tricolors and after I placed the order with the flag company, the special branch contacted me on the basis that only Provos would be organizing an event that used the tricolor. I got involved in political issues for cultural reasons. The driving force for me was what I saw as the destruction of the cultural identity of a people.

On being libeled.

It was a bizarre period. Because I was chairman of a national commemoration committee, I had to defend what we were doing on radio debates, and Shane Ross issued a statement saying, “Robert Ballagh represents the interest of the IRA.” After the peace process was in place, I sued both the Sunday Times and the Irish Independent newspapers and I got thirty thousand [euros] out of the Indo and thirty-five out of the Sunday Times, who had said I represented the cultural wing of the IRA. They went through 30 years of files and found not one piece of evidence that I supported violence.

Favorite music?

I love rock & roll. I’m old enough that I was in at the start. When I was thirteen my father brought me to Rock Around the Clock and I was transfixed and became obsessed. I’m lucky enough that the people I started off listening to were Little Richard, Chuck Berry, Jerry Lee Lewis, and Fats Domino etcetera. I’m kind of snobby about it. When I hear young people talking about music, I think, “you don’t know what good music is.” I also adore Bernard Herrmann who wrote the music for Alfred Hitchcock movies. Scorsese recognized Herrmann’s greatness and took him out of retirement to do the music for Taxi Driver and the remake of Cape Fear, which was Herrmann’s last movie before he died. Love his stuff. His music for Vertigo is mesmerizing. And I love Nino Rota, who did the music for Fellini’s films. And then I love the classic American music – Cole Porter and George Gershwin, and I’m fond of classical music but more baroque. I love Vivaldi – so very Catholic stuff. I used to always let the radio run in the studio, but more and more I’m playing CDs rather than listening to current affairs, which is so depressing.

Favorite sound?

Every Sunday at around 12 o’clock my grandchildren come in calling out “Granddad Bobbie.” I like that.

How do you know when a painting is finished?

That’s a hard one. A crucial skill is knowing when to stop.

Note: Ballagh’s stained-glass window is now installed in Quinnipiac University’s Famine Museum.

A selection of Ballagh’s work:

I am an Irish non national studying Art.

Thank you for this article. I am only just learning about Robert Ballagh and I love this interview,

thanks for the good work.