Recently published books of Irish and Irish-American interest.

Recommended:

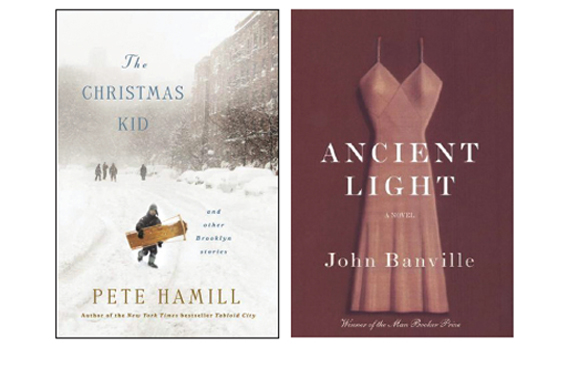

The Christmas Kid

Pete Hamill is New York’s City’s citizen chronicler. The constantly changing metropolis features in most of his books and articles. For many years he worked as a reporter and columnist for the New York Daily News. His novel Forever (2003) is perhaps his best known paean to the city, a sweeping historical saga that takes us though the growth of the city from pre-revolution days to 9/11.

In his new collection of stories, The Christmas Kid, Hamill returns to his old neighborhood in Brooklyn. Vivid characters such as “Wonderful Kelly” and “Facts McCarthy” abound, but it’s not all Irish. “The Christmas Kid,” the title story is a poignant tale of a young Jewish boy that evokes the Nazi death camps. In another story called “A Death in the Family,” Hamill writes about the drug lords who brought death and destruction to New York neighborhoods in the late ’60s and ’70s. “There was a plague at home and the plague was called heroin. If the neighborhood was a family, then the family was dying,” he writes.

Many of the stories in this collection were originally written as O. Henry style stories for the Daily News, and Hamill’s skill as a reporter is evident here. His simple descriptions and careful observance record a place and time that is physically no more but is imprinted on the DNA of the city. Taken as a whole, The Christmas Kid leaves the impression that Hamill’s great love is New York City and his mission is to open a portal to the vanished world that lies beneath and alongside the modern trappings of today’s New York. He succeeds.

(Little, Brown and Company / $14.00 / 288 pages)

Ancient Light

It has been three years since John Banville’s last novel, The Infinities, was published. But if we haven’t been missing Banville, it’s because he hasn’t been absent. Since The Infinities he has issued three new mysteries under his pseudonym Benjamin Black and collaborated with Glenn Close on the screenplay for Albert Nobbs. Maybe this is why it feels as though Ancient Light, Banville’s fifteenth novel, has snuck up on us.

What comes as an even greater surprise is that Ancient Light links back to two previous works, Eclipse (2000) and Shroud (2002), belatedly forming a trilogy. In Eclipse, Banville introduced us to Alex Cleave, a stage actor who, after freezing during a performance, retreats to his empty childhood home and ruminates in writing. Much of his reflections concern his troubled daughter, Cass, who by the end of the novel has drowned herself in Italy. Shroud then told us Cass’s story as her father may never know it. Her scholarly work led her to discover damning secrets about an acclaimed literary theorist, the anagrammatically named Axel Vander, with whom she was intimately involved.

Ancient Light revisits Cleave ten years later. He is still grieving for Cass, still obliquely trying to make sense of everything through writing, but this time he is consumed by another memory, that of his first love affair, which took place in the spring and summer he was fifteen, with his best friend’s thirty-five-year-old mother, Mrs. Gray. It’s an inverse Lolita, and though Cleave is a much more sympathetic figure than Humbert Humbert, his memory is also fickle, and his way of processing things is often exceptionally accommodating to the way he wants to see them. In an uncomfortable turn of fate, Cleave is invited to star in a film adaptation of the definitive biography of Axel Vander, appropriately titled The Invention of the Past. The narrative meanders between Cleave’s recollections of Mrs. Gray and his present, as the film and his young co-star push him to revisit Cass’s death.

Banville has done this before, with the Revolutions Trilogy (Doctor Copernicus, Kepler and The Newton Letter) and the Frames Trilogy (The Book of Evidence, Ghosts and Athena). The linking threads of the Cleave novels (it might be hasty to declare them a trilogy) create the most complex pattern yet, connected as they are by meditations on family, performance, scholarship, identity, and – as always – memory.

(Knopf / $25.95 / 304 pages)

Fiction:

Astray

When you first dip your toe into Astray, Emma Donoghue’s new collection of stories, it takes some getting used to. These brief, often fantastical glimpses into a wide range of minds and lives are much more fleeting than the wholly engrossing narrative of Room, Donoghue’s bestselling 2010 novel, which earned her wide acclaim. But as we read on, we find that, as in Room (which was based on the Fritzl case), these stories are mostly drawn from real-life figures and events, and Donoghue’s talent for capturing each character’s idiosyncratic voice is just as strong as it was when she so brilliantly inhabited the perspective of 5-year-old Jack.

Astray is divided into three sections: Departures, In Transit, Arrivals and Aftermaths, and the stories span four centuries, from the Puritan society of Cape Cod in 1639 in “The Lost Seed,” to Newmarket, Ontario in the mid-1900s in “What Remains.” Each is followed by a brief afterword of sorts, in which Donoghue gives the facts on which the story is based, or the context by which it was inspired. These are the forgotten but (mostly fascinating) ones of history: Matthew Scott, handler of the famous circus elephant Jumbo; Lewis Cass Swegles, the Secret Service agent who infiltrated a gang planning to steal Abraham Lincoln’s corpse. The collection’s afterword links them all together: These are stories of migrants – people who have “gone astray,” crossed both physical borders and more intangible ones of religion, politics, sex or race. Donoghue, is herself an immigrant (she grew up in Dublin and now lives in London, Ontario), and that makes these stories some of her most personal writing so far.

(Little, Brown and Company / $25.95/ 288 pages)

Dublinesque

The Irish are wonderful at writing about Ireland. But, to borrow a phrase from Ulysses that repeats throughout Enrique Vila-Matas’s Dublinesque, “always someone turns up you never dreamt of,” who shines a keen and fresh perspective. With Dublinesque, Vila-Matas is that someone. One of Spain’s leading contemporary writers, Vila-Matas is highly regarded for his meta-fictional adventures that build layer upon layer of references to other writers and works – mostly real, some not. Of his 21 novels, only four have been published in English, and we are very lucky that Dublinesque is the latest.

Masterfully translated by Anne McLean and Rosalind Harvey, Dublinesque, which borrows its title from the Philip Larkin poem by the same name, centers on Samuel Riba, an esteemed literary publisher of the old guard who, having closed his publishing house, now spends most of his days sitting in front of his computer (he likes to Google himself), worrying his wife with his reclusive behavior, and regretting that he never discovered that one brilliant author – a Beckett of his generation, say – who would have made it all unequivocally worth it.

Now a teetotaler after years of heavy drinking, Riba becomes obsessed with a vivid, possibly portentous dream he had two years prior, while recovering in hospital, of visiting Dublin. Thinking that a trip to Ireland might be just the thing, he gathers three of his writer friends to make the journey with him. His secondary motive: to host a funeral for the golden days of literature, the “Gutenberg Galaxy,” as he calls it, at Glasnevin Cemetery on Bloomsday.

Joyce and Beckett are of course everywhere, and Flann O’Brien and Brendan Behan have their time in the spotlight. Contemporary Irish writers such as John Banville, Colum McCann, Matthew Sweeney and Claire Keegan get nods in the narrative as well, and some unfamiliar names had this reader running for Google to see whether they were real. John Ford makes a few appearances, as does a Liam Clancy song. In addition to being a beautifully executed literary balancing act, Dublinesque is a love letter to Irish literature, by someone who knows it very well.

(New Directions / $16.95/308 pages)

Non-Fiction:

Atlas of the Great Irish Famine

Over the past few decades, the Great Irish Famine, once a topic addressed quietly and with no small amount of contention, has become a rich area for scholarly research. Atlas of the Great Irish Famine, a 712 page tome released by University College Cork and published in the U.S. by New York University Press, is a testament to how far our collective understanding of the famine and its consequences have come.

Edited by John Crowley, Mike Murphy and William Smyth of UCC, and featuring contributions from scores of other scholars, historians and voices in the field, the Atlas achieves the remarkable feat of communicating both the most technical aspects of the famine as well as the most emotional. Over 200 maps, drawn from the censuses of 1841 and 1851, show the devastation of the famine at the national, provincial and county level – dwindling land values, population decline that remains shocking to this day. The beautifully reproduced maps and charts are interspersed with wrenching and exacting chronicles of the famine’s devastation in different counties and parishes; accounts of life in the workhouses; personal histories. A section entitled “The Scattering,” which chronicles the journeys of famine immigrants to New York, Boston and Toronto, among other places, offering glimpses of their lives there, will be of particular interest to Irish Americans.

This Atlas, the most thorough portrait of the famine to date, puts us on the right side – the aware and communicative side, that is – of history.

(NYU Press / $75.00 / 712 pages)

Children’s Books:

Oisin the Brave: Moon Adventure

In this whimsical, delightful and educational tale (intended for children ages 3-7) Oisin the Brave, a modern-day Irish hero for the younger set, embarks on an out of this world adventure. Studying the night sky with his sidekick Orane the Dragon of N’Scaul, Oisin notices a strange flashing light coming from what appears to be the surface of the moon. Before long the friends power up their magical Dolmen of Time and are off to discover the cause.

Waiting for them are the moonians, gentle alien creatures who have the added benefit of teaching little readers some basics of the Irish language. The names on their shirts (Aon, Dó and Tri) reflect the number of eyes they each have. Interestingly, there is already an Irish flag on the moon’s surface – a positive sign for the source of that bright light. Despite a humorously portrayed language barrier, the moonians eventually lead Oisin and Orane to the source, a wrecked spaceship. They approach with trepidation, but the surprise is a good one. It’s their friend Princess Eire, who was off on an adventure of her own.

Building on the Irish within the story, the final pages of the book contain a nicely illustrated Irish lesson, with the names for animals, shapes, colors and emotions. This is the first in a new series by Michelle Melville and Derek Mulveen, founders of the recently launched brand Eire Kids. We can’t wait to see what’s in store for Oisin next.

(Eire Kids / $7.00 / 24 pages)

Leave a Reply