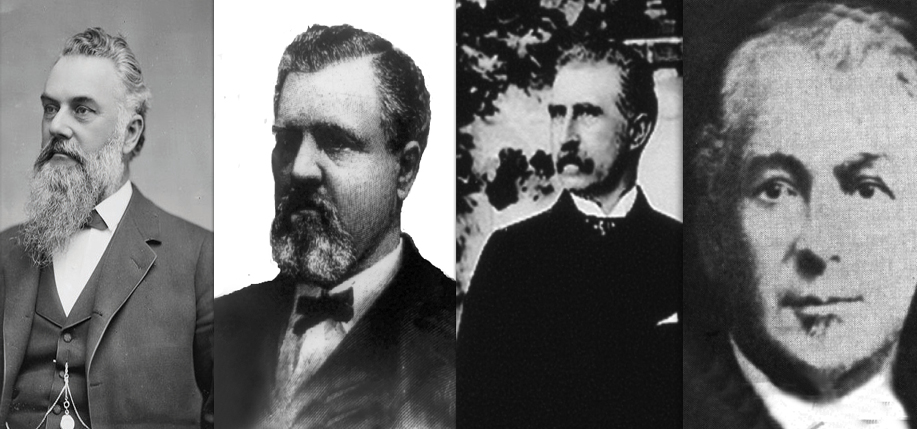

The Comstock Lode in Nevada, uncovered in 1859 by two Irish laborers, ultimately produced more than $500 million worth of silver, a large share of which went to the Irish-American “Big Four” – James Fair, James C. Flood, John Mackay, and William O’Brien – who had left New York for the bigger opportunities of the Far West. Dr. Roger D. McGrath tells their story.

Grinding poverty, the Great Famine and other lesser famines, and thousands of evictions, caused millions of Irish to immigrate to America during the 19th century. A good number of these Irish found their way onto the frontier, especially the mining frontiers. Wherever there was a rush to a new strike, the Irish were sure to be on board. John Mackay, James Fair, William O’Brien and James Flood were four such Irishmen. They were destined to become partners and to be known worldwide as the Silver Kings.

John W. Mackay was the engineering genius of the Silver Kings. One of four children, he was born in Dublin in 1831 and immigrated with his family to New York in 1840. He reached the California gold fields in 1951; by then he was a striking figure – tall, lean and muscular, ruddy-faced, blue-eyed, and dark-haired. He enjoyed hard physical work and mining camp life.

He had almost no formal education and had stuttered badly when he was young, but he was blessed with extraordinary intelligence. Nothing escaped his keen mind and no engineering problem was beyond him. He could explode with rage, but he usually kept his temper in check. For relaxation he loved music and drama.

James G. Fair was self-serving and egotistical. However, he was a mine superintendent without peer and a shrewd financier. He had enormous energy, a trenchant mind, and a natural aptitude for all things mechanical. He regularly took advantage of the latest innovations in mining machinery. Born in Ireland in 1831, he immigrated with his family to Illinois during the early 1840s and joined the rush to California in 1849. Unlike his name, Fair had brown eyes, a dark complexion, and wavy black hair. He was handsome, powerfully built, and had a way with words. “The Blarney of his race had not been omitted from his makeup,” said the San Francisco Chronicle. “When it suited his purpose… his compliments could charm a robin off a fence post.”

William S. O’Brien was a large man of erect carriage with a head of prematurely white hair. His size, posture, and hair gave him a dignified appearance. Unlike his partners, he was soft-spoken and mild-mannered with an avuncular, kindly quality about him. He was the least forceful of the Silver Kings but his gregarious and genial nature made him the most popular. Although he did not carry his share of responsibilities in the partnership, he contributed more than he was usually given credit for. Born in Ireland in 1826 he was brought to New York as a small child and arrived in California in 1849.

James C. Flood was the only Silver King not to have been born in Ireland. He was born in New York in 1826, the son of Irish immigrants. In 1849 he sailed around the Horn to California. Below medium height, Flood had a ruddy complexion, a short neck and massive shoulders. He was so impressively muscled that strangers often thought he must be a gymnast or wrestler. He had a quick wit, a shrewd mind, a volatile temper, and a powerful drive to succeed. He was a genius in trading stocks and finance.

Mackay, Fair, O’Brien, and Flood all spent the early 1850s prospecting and mining in California, and each had a degree of success. With his earnings from the diggings, O’Brien opened a marine supply store in San Francisco. Flood, with the money he had made, opened a livery and carriage shop just down the street from O’Brien. Both lost their businesses, though, in the Depression of 1855. They then joined forces and opened a saloon. O’Brien reasoned that the only thing that did not go down in the depression was the consumption of alcohol. He was right and their saloon thrived.

By the early 1860s, Flood and O’Brien were dabbling in mining stock, buying and selling shares in mines that had tapped into the great Comstock Lode. (Two Irish prospectors, Peter O’Riley and Patrick McLaughlin, had discovered the Comstock Lode, the Unites States’ first major source of silver ore, in 1859. Virginia City, Nevada, sprang up as a result of the discovery.) Flood proved to have uncanny ability in stock trading. He made one smart decision after another and within a few years he and O’Brien had amassed a small fortune. In 1868 they opened their stock-brokerage office in San Francisco.

Meanwhile, Mackay and Fair had been prospecting in California and Nevada. Mackay and his partner in those early days, Jack O’Brien (no relation to William O’Brien), crossed the Sierra to Nevada upon hearing of O’Riley and McLaughlin’s strike. By the time they reached the Great Divide, above Virginia City, they were nearly broke, having only a 50-cent piece between them. O’Brien pulled the coin from his pocket, looked at it, and then threw it down the mountainside toward Virginia City. Now without a cent to their names, Mackay and O’Brien strode into town.

Mackay worked as a pick-and-shovel miner for four dollars a day, then as a timber man for six. Soon he developed his own business, excavating and fortifying tunnels. Much of the pay was in the form of stock certificates. Most of these proved worthless but a few profitable ones gave him enough money to buy the Kentuck, a mine whose ore had supposedly been exhausted. Mackay got a loan from fellow Irishman James Phelan (his son James Duval Phelan would later become mayor of San Francisco and a U.S. senator) and sank a new shaft in the Kentuck. Just before Phelan’s note was due, Mackay hit a small but rich deposit. During the next several years the Kentuck paid over a million dollars in dividends. Mackay had always said he would retire as soon as he had $25,000 in the bank. He now had considerably more than that, but his appetite had only been whetted for new adventures and enterprises.

James Fair arrived in Virginia City in 1865 after a number of successful mining ventures in California. Less than a year after his arrival he was made superintendent of the Ophir, one of the true bonanza mines of the Comstock Lode. In 1868 he entered into a partnership with Mackay, and shortly afterwards the Comstock miners joined forces with San Francisco stockbrokers Jim Flood and Bill O’Brien. The famous partnership was now in place.

By the early 1870s, through wise investments and daring gambles, the four Irishmen were challenging “Ralston’s Ring” for control of the Comstock. The ring was headed by William C. Ralston, the president of the Bank of California, and his henchmen in Virginia City, led by William Sharon. Sharon was the most hated man on the Comstock. He was a cold, embittered and treacherous financier who was wreaking vengeance on Virginia City businessmen and speculators for the loss of his own fortune in 1864. By working with Ralston he had regained far more than he had lost, but his desire for vengeance was insatiable. Ever shrewd and calculating, Sharon made loans through the Bank of California to mines on the Comstock, and then delighted in foreclosing on them when harsh repayment schedules were not met. In addition, he got control of all the important mills by processing ore at a loss in the Bank of California’s Union Mill and then buying the other mills one by one as they went out of business.

Sharon looked the part of the ruthless scoundrel. He had black, beady eyes, a jet-black mustache, and an expressionless face that a professional gambler might envy. He wore a long, black frock coat and a big, black hat.

Sharon hated “those Irishmen,” as he called Mackay, Fair, Flood, and O’Brien and decided to see to it that the audacious upstarts were crushed. In February 1872 the Irishmen bought a controlling interest in the Consolidated Virginia for $100,000 from Ralston’s Ring. Sharon was ecstatic. He gleefully reported to Ralston that the Irishmen had been taken. The Consolidated Virginia, said Sharon, was worthless, “a bankrupt piece of property.” Over $1,000,000 had already been wasted in fruitless exploration of it.

Nonetheless, the Irishmen had a hunch that if they cut a new tunnel at a deeper level they would hit a vein of ore. For several months they tunneled, pouring $200,000 into the Consolidated Virginia, but hoisted up nothing but worthless rock. Sharon and Ralston, and the Ring, laughed heartily. Then one day Mackay and Fair, who were supervising the actual work in the mine, hit a delicately thin vein of ore. They tried to follow it but it disappeared. Then they found it again, and again it disappeared. Then they found it once again and this time the vein began to widen; to more than a foot, then to several feet, to a half-dozen feet, to twelve feet. At this point, Mackay and Fair sent word of the discovery to Flood and O’Brien in San Francisco who quickly bought up as much outstanding Consolidated Virginia stock as they could.

Meanwhile, the deeper the new tunnel was sunk in the Consolidated Virginia the wider the vein became. At the 1,500-foot level the vein was more than 50 feet wide. The ore was so rich that waste rock had to be added to it in order to put it through the stamp mill. The Irishmen had discovered the heart of the Comstock Lode – “The Big Bonanza.” For the rest of their lives they would be known as the Silver Kings.

By 1875 the Silver Kings had become fantastically wealthy. The Consolidated Virginia was paying monthly dividends of a million dollars, equivalent to 20 million in today’s dollars. From 1873 through 1882, the Consolidated Virginia yielded some $65 million in gold and silver, and paid almost $43 million in dividends.

The Silver Kings all lived riotously well and died with multi-million-dollar estates. William O’Brien supported all his close relatives, especially the McDonough and Coleman families of San Francisco, and he left an estate of $12,000,000 at his death in 1879. O’Brien loved to spend his afternoons in McGovern’s saloon on Kearney Street in San Francisco. There he conversed with old friends and played endless games of poker. At his elbow he always kept a tall stack of silver dollars. It was understood that any regular customer of McGovern’s saloon who happened to be down on his luck was welcome to help himself. Whenever the supply dollars began to run low, O’Brien would summon the bartender, pass him a $20 gold piece, and the stack of silver dollars would be replenished.

James Flood bought San Francisco real estate, erected numerous buildings, funded new business ventures, and established the Nevada Bank, which later merged with Wells Fargo. He also made regular and large contributions to various charities and to orphan asylums and old people’s homes. He and his wife, the former Mary Leary of County Wexford, raised their children on a fabulous 35-acre estate at Menlo Park.

James Fair was elected to the U.S. Senate from Nevada. Although he was faithful in his attendance during the first session, soon, being a man of action, he grew bored with tiresome Senate deliberations and thereafter was mostly absent. He apparently had plenty of time to pursue women. Mrs. Fair, the former Theresa Rooney, divorced him on grounds of “habitual adultery” (he was the first senator to be so charged). She received the family mansion and nearly $5,000,000 in cash. At the time it was said to have been the largest divorce settlement ever awarded. Fair continued his wild ways, and upon his death a half-dozen women who hoped to share in his estate came forward and claimed to have been wives or mistresses. By the time of his death in 1894 he had accumulated an estate estimated at some $40,000,000. Rents from the property he owned in San Francisco averaged $250,000 a month. He was the city’s largest taxpayer. Before he died, he also found time to establish two banks, Mutual Savings and Merchant’s Trust, and to build a railroad.

John Mackay created the Commercial Cable and Postal Telegraph Company, laid cables across the Atlantic, and broke the Western union monopoly. He made more millions. His estate was estimated at some $50,000,000 when he died in 1902. During his lifetime he had given away more than $5 million in gifts. He had also torn up IOUs worth more than $2 million.

He could never say no to a friend or even a casual acquaintance. When the great fire of October 1875 destroyed the central part of Virginia City, including the town’s only Catholic church, St. Mary’s of the Mountains, Mackay donated much of the money to have St. Mary’s rebuilt bigger and better than ever. During a slow period on the Comstock, Mackay secretly paid a Virginia City grocer to supply provisions to any miner out of work. He also was the largest contributor to the Sisters’ Hospital, requiring only that his donations be kept confidential.

Mackay remained vigorous and athletic nearly until the day he died. While he lived in Virginia City, he boxed nightly at the local gymnasium. Later, in San Francisco, he had a gymnasium built in the basement of the Silver Kings’ bank. One of those who learned to box there was an American-born Irishman, James J. Corbett, known as “Gentleman Jim,” who later became the heavyweight champion of the world when he defeated another American Irishman, the famous John L. Sullivan, in 1892.

In his 60s Mackay could still pin nearly any man he met in arm wrestling. At 60 he pummeled a wealthy Englishman who had offended him. As one observer noted, Mackay had “a marked hostility to Englishmen.” On another occasion, James White, a member of Parliament from Brighton, England, attended a stockholders’ meeting of the Consolidated Virginia on behalf of British shareholders. When White claimed the Silver Kings were not dealing honestly with the shareholders, Mackay sprang to his feet in a rage and exclaimed: “It seems odd to hear an Englishman charge anyone with dishonesty.”

Mackay hated pretense and artificial social distinctions. In England and France, where his wife visited frequently, Mackay loved to play the role of the uncouth miner from the American West, especially when being entertained by English nobility who hoped that some of this wealth would rub off. He took malicious pleasure in recounting his boyhood in Ireland where the English had insured that there was seldom enough to eat. He delighted in telling of the pigs and cows that shared his family’s one-room cottage. While the English sycophants surrounding him ordered French delicacies, Mackay, one of the wealthiest and most powerful men in the world, ordered corned beef and cabbage without batting an eye.

John Mackay, James Fair, James Flood and William O’Brien were only a few of the larger-than-life characters, many of them Irish, who played major roles in the opening of the West.

I have read this with great interest. I don’t have much family history but my father did tell me that my great-great-grandfather Thomas Alexander drove a team for the mines in Virginia City and played poker with Flood, Fair and MacKay. So nice to see a connection to history. Thanks

Karen Minkey Mapes

My great, great, great uncle was James Graham Fair, unfortunately the money didn’t trickle down this far. I’m as broke as the ten commandments… Ha Ha Ha

Chip Fair….hey sorry to hear about that! (lack of funds coming your way) Your Great uncle was basically a billionaire back then….compared to todays $$

Ive got a load of his signatures on checks from various mines and mills….dating wayyyy back to 1800s…..neat stuff….

Sorry left out the link.

https://cdnc.ucr.edu/cgi-bin/cdnc?a=d&d=SFC18941230.2.48

The following link is to a story in the San Franciso Call newspaper dated Dec 30, 1894 shortly after Fair’s death. It gives details of Fair’s will including a bequest of $10,000 to Mary Jane Lundy who was Fair’s niece and my grandmother. The first reference say 510000 but this must be a transcripton error mistaking a “$” for a 5. A second reference reports $10,000.

Fair was my great great uncle also. He left my great great grandmother $250,000 at the time of his death. We still have some of the farm land she purchased at that time

After a camping trip to Tahoe and a side trip to VC, l have become totally engrossed the geology and development history of the lode. As I understand it, the reason none of Fair’s wealth trickled down to his distant relatives is that despite his talents, he was a miserly hoarding bastard and his estate ended being picked apart by by a bunch bottom-feeding, blood-sucking lawyers. I feel for you Chip.

James Fair was my grandmother’s uncle. He brought her out from Ireland in, I believe, the late 1870’s. She told my mother that she only came for a visit, but could not face the trip back. She married in Iowa in 1882. My mother, born in 1903 after Fair’s death, did not inherit anything, but her mother and older siblings did. My grandmother told my mother that they did not inherit as much as they might have because Fair did not approve of her marriage. Nevertheless, it was enough for my mother’s oldest sister to attend one of the seven sisters women’s colleges. My daughter just noticed Fair’s name with 2 of the other 3 partner’s in a list of the world’s wealthiest in Malcolm Gladwell’s book “Outliers”.

Fair left 2 daughters and a son (who died w/o issue in a car crash in 1902): Mrs. Hermann Oelrichs (née Theresa “Tessie” Alice Fair) and Virginia Graham Fair (who later married William Kissam Vanderbilt II)

The 2 sisters started building the Fairmont Hotel in 1902, selling it just days before the great earthquake and fire.Tessie Fair Oelrichs repurchased the property in 1908, retaining ownership until 1924

The 2 daughters had children by their wealthy husbands

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theresa_Fair_Oelrichs

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virginia_Fair_Vanderbilt

thank you for the link CDNC. I found a wealth of information about my great grandfather and grandfather Lewis James Hanchett who worked for Mackay as mining agent. My grandfather Lewis Edward Hanchett did become very successful and developed the Union Station with part of his fortune. I am the only grand child from the family.