Rex Ingram: The clergyman’s son who became one of the biggest directors in Hollywood and discovered Rudolph Valentino.

There would have been no shortage of Irishmen who came ashore in New York that June day from the RMS Baltic – the Belfast-built liner that carried up to 3,000 passengers on the regular route from Liverpool to Cobh to New York. Just one page of the passenger manifest for June 25, 1911 shows arriving passengers from all over the country – from Bantry and Cork, Clonakilty and Galway, from Lurgan in the north, and one particular passenger from Co. Offaly with fifty dollars in his pocket: a 19-year-old, just short of six feet tall, with black hair and gray eyes, named Reginald Ingram Montgomery Hitchcock.

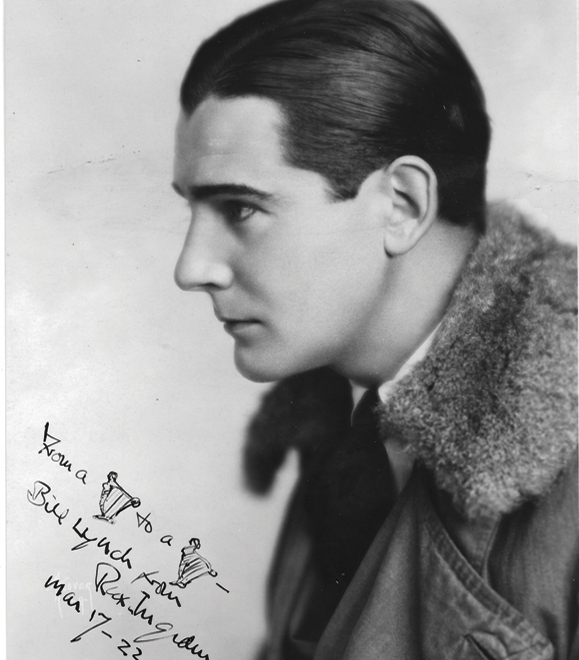

The only thing that would have made him stand out was his very handsome face, which would one day decorate international magazine covers and publicity shots. But as he set out from New York to New Haven, Connecticut for a clerk’s job on the railroad, he was just another anonymous Irishman, the latest arrival among the millions that for decades had come to make their name in America. Except that this one did make his name: within fifteen years, the clergyman’s son from Kinnitty would be Rex Ingram, one of the biggest directors in Hollywood, maker of blockbuster hits of the silent era, discoverer of the great Rudolph Valentino, married for life to one of the movies’ most beautiful stars, and a celebrity in his own right, with his name burnished above the titles of his films: “A REX INGRAM PRODUCTION.” But his star would burn out as quickly as it had ascended.

Rex Ingram was the first major Irish film director (an older Dubliner, Herbert Brenon, had a substantial career and even received an Oscar nomination, but was never really in Rex’s league). Except among movie aficionados, his name had largely been forgotten, possibly because he only made one film after the talkies came in. The big silent directors who survived into the talking picture era – John Ford, Alfred Hitchcock (no relation to Rex), Cecil B. DeMille, King Vidor – earned their place in the film pantheon for the entirety of their careers. But silent-only directors like Rex Ingram drifted into obscurity as the popular taste for their films declined.

More recently, though, the tides of fame have turned. Large-scale restorations of great silent films – among them, Rex’s 1921 blockbuster The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse – have demonstrated the incredible flair and virtuosity of the silent masters. At the same time, the public’s imagination has been stimulated by modern imaginings of the pre-talking era, most notably in this year’s Oscar-winning The Artist and in Martin Scorsese’s loving tribute to silent movies, Hugo. The Irish film scholar Ruth Barton of Trinity College Dublin is working on a major Ingram biography. The National Library of Ireland is preparing a Rex exhibition based on the priceless collection donated to it by the late film scholar Liam O’Leary. And the Irish Film Board has provided seed money to a team of filmmakers (full disclosure: including myself) to produce a feature documentary on the great man. His time seems to have come again.

After a few months working for the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad, Rex signed up at his local university – Yale – to study sculpture. He was a talented artist, whose teacher was the celebrated Lee Lawrie (creator of the great Atlas outside Rockefeller Center in New York). But the burgeoning film business, then mainly based in and around New York, had greater appeal to the young Rex, barely out of his teens. He met the Edison family through a Yale pal, and dropped out of school to take a job at the famous Edison Studios in the Bronx. As an artist, he drew titles and painted sets and portraits. But he was also given a shot at other jobs – first writing scripts and then performing on screen. He looked great but was not really an actor, although that did not prevent him from appearing in a large number of films for Edison and the Vitagraph company. After a stint at Fox writing more scripts, he was hired in 1916, at the age of 25, but a veteran of dozens of movies, to be a director for Carl Laemmle’s Universal Film Manufacturing Company. After Rex made a couple of films at Universal’s studios in New Jersey, Laemmle transferred him to the new epicenter of the business in Hollywood, California, where Rex directed six more pictures for the combative mogul.

Unfortunately, Rex was combative himself, and had been since his schooldays. While he could be a knight in shining armor, fearlessly entering combat on behalf of a person who he viewed as wronged or slighted, he could also pick the wrong fights, as he found at Universal. He clashed with Laemmle and was fired, although, after a hard spell in the wilderness, he was allowed to come back, thanks to the influence of the Waterford-born Universal executive Pat Powers. By the beginning of 1920, still only 27, he was hired as a director by the Metro studios for $600 (more than $7,000 today) a week. This was where Rex’s career began to take off.

Rex did not leave his ability to make trouble for himself behind at Universal, where his crew knew him as the “crazy Irishman.” But Metro paired him with the great cameraman John Seitz – who went on to shoot such classics as Double Indemnity and Sunset Boulevard – and a great partnership was formed. Rex was a demanding perfectionist who was known to grab paint and touch up sets even at the height of his fame. Seitz was a painstaking artist who understood the science as well as the art of filmmaking and who strove to give Ingram exactly the visual texture that inspired his painterly inner eye.

Rex also had his share of luck. When he joined Metro, it was a small studio making inexpensive films at around $20,000 a pop. But its wealthy new owner, Marcus Loew, had bigger ambitions. Through the efforts of June Mathis, the visionary head of Metro’s script department, the studio paid $20,000 to buy just the movie rights to a runaway anti-war bestselling novel, The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, from its Spanish author, Vicente Blasco Ibáñez. Loew poured in one million dollars – equal to the cost of 50 of the studio’s regular movies – to make the film. Mathis wrote the script and brought in Ingram to direct.

Ingram went to work, building huge sets around Los Angeles, including a French village complete with a castle that is spectacularly blown up by a German assault during a reenactment of the Battle of the Marne. The vast panorama of the novel – from Buenos Aires to Paris, from Lourdes to the battlefields of the First World War – was meticulously recreated on film. But the spectacular elements of the picture supported a human story of love, loss and redemption against the background of catastrophic, devastating warfare. Its most sensational success was Mathis’ and Rex’s astonishing discovery, an Italian bit part player and former taxi dancer named Rudolph Valentino, whose sinuous, lascivious performance of the tango in an Argentine dive turned him into an instant international star.

Four Horseman was the most successful film of 1921 and gave Loew an ample return on his huge risk. It also made Ingram a directing superstar. Of Rex’s work the playwright Robert Sherwood wrote, “the grandiose posturing of D.W. Griffith and Cecil B. DeMille appear pale and artificial in the light of this new production.” Rex had a free hand at Metro for his future pictures. And he had another hand as well, that of his leading lady, Alice Terry, whom he married later that year.

Alice was very pretty, with an elfin face and big eyes. Her features had the expressiveness that was essential to a silent movie star. And she was Irish; her father, Martin Taaffe, was from Kildare before moving to the USA. After his early death, Alice’s mother moved the family to California, where Alice worked in small jobs in the movie business before Ingram spotted her, becoming her champion. After her role as Marguerite in Four Horsemen, she became one of the major leading ladies of her time. And, once married to Rex, the two became yoked in the public consciousness as a celebrity couple, photographed together, appearing in magazine spreads and newspaper articles, posing for postcards and publicity shots. All the while, Alice flourished as the beautiful heroine of Rex’s continuing successes for Metro, in popular costume dramas such as The Prisoner of Zenda and Scaramouche.

But Rex just couldn’t stop picking fights, most notably with Marcus Loew’s new partner in the merged Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer studios, Louis B. Mayer. Even though Mayer respected Ingram, Rex was unable to contain his loathing of the man who was his boss. When Mayer offered Rex the plum directing job of the 1920s – the mega-budget biblical blockbuster Ben Hur – Ingram made so many unreasonable demands that Mayer gave up and hired someone else. Ben Hur, under the direction of Fred Niblo, became one of the most successful films in movie history.

Instead, Rex and Alice headed for France. He had made one film there, The Arab in Nice, and believed that if he returned to France, he could maintain control of his films, free of studio interference. His next big project, Mare Nostrum was another hit novel by the author of Four Horsemen, Vicente Blanco Ibáñez, a melodramatic tale of war, espionage, love and intrigue set in the Mediterranean during World War I. In adapting it, Ingram was the usual uncompromising perfectionist. The production, shot in France, Italy and Spain, lasted 15 months. One scene was filmed 185 times. Russian extras were required repeatedly to plunge into the Mediterranean – very cold despite its reputation – warmed by nips of vodka until they could take no more. Hundreds of octopuses died to achieve a single shot. Huge amounts of film were discarded. Although the released film was shorter than Ingram had intended, it was once again warmly received by the critics. In Dublin, the Evening Herald said that it was “easily the finest picture that has been released this year.”

As the result of a series of complex deals involving MGM, Ingram found himself the owner of the Victorine Studios, with ambitious plans to build Hollywood on the Riviera. He and Terry received the great and the good in Nice. He directed The Magician, a sensational thriller based on a novel by W. Somerset Maugham, and The Garden of Allah, about a trappist monk in North Africa who abandons his vows and marries, only to return to the monastery at the movie’s end. Although it was another critical and commercial success, MGM decided to end its contract with Ingram. His closest associates had already returned to Hollywood. Ingram continued to make films in Nice, but his relationship with his business partners deteriorated, and he engaged in prolonged and unsuccessful litigation with them. He and Alice both found the arrival of sound films uncongenial. After a couple of attempts at talking pictures, Ingram brought his cinema career to an end in 1932. He was just 39.

Ingram’s energies did not dissipate however. His love of North Africa led to extensive travel in the region, and an apparent conversion to Islam. He moved to Cairo and accumulated a large collection of Arab art. He returned to sculpture. He took up writing, publishing two novels. However, sickness that occurred during his spell in Egypt left him with permanent coronary problems. He returned to Hollywood in 1936 and settled down with Alice again – they had been separated for two years. After World War II, he traveled back to North Africa to recover his art collection, which had been deposited in Cairo. During an arduous journey, he suffered repeated heart attacks. Returning home, he set out on more travels and became sicker, also catching malaria in Mexico. He died in 1950, aged 57.

Despite the virtual eclipse of his career, Ingram’s star never completely waned. The great director David Lean (Lawrence of Arabia) cited Rex as a key influence. Another great filmmaker, Michael Powell (The Red Shoes), who got his first job working on The Magician, revered him. And when Martin Scorsese was reimagining the silent era in Hugo, he played back The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse in his editing room for inspiration. These directors all echo the view of the legendary Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer production chief Dore Schary who, when asked to name the great pioneer Hollywood directors, replied “D. W. Griffith, Rex Ingram, Cecil B. DeMille, and Erich von Stroheim – in that order.”

Just to let you know that there is now an annual festival that is held in memory to the talents of Rex Ingram. This is the Nenagh Silent Film Festival and it is held in a town where the great Rex Ingram once lived as a young man, which is also the setting where Rex Ingram saw his first production at a traveling circus back in 1901. This festival was held for the first time during February 2013 and as part of the the celebrations, a granite plaque in Rex Ingram’s honour was erected. The next Nenagh Silent Film Festival will be held from February 13th to February 16th.