Recently published books of Irish and Irish-American interest.

Recommended: Summer Mysteries

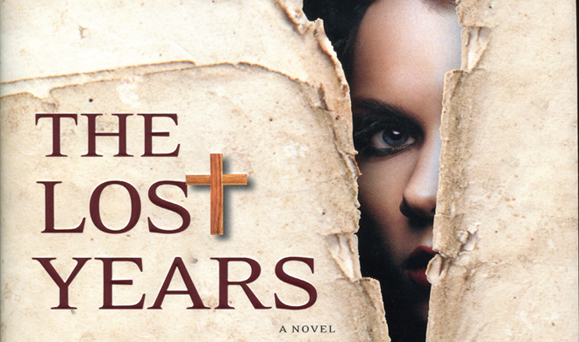

The Lost Years

Mary Higgins Clark’s latest novel, The Lost Years, is a mystery-suspense exploring the topics of brain-altering illness (a Higgins Clark favorite) and Biblical scholasticism (a new one). The story centers around the shooting and death of a retired professor. A letter, supposedly written by Jesus Christ, which was stolen from the Vatican in the 1400s, is the item of intrigue that may have inspired the murder. The professor’s jealous wife, who suffers from Alzheimer’s disease, is the prime suspect.

The couple’s 28-year-old daughter, Mariah, is the hero of the story. As such, she carries the burden of solving her father’s murder and of clearing her mother’s name. “Mariah, I’m so sorry. I can’t believe it. It seems so sudden,” a mourner laments in the opening pages. Well, yes, the man was shot. That would seem sudden. Immediately, this mourner becomes a potential culprit.

The fun with a mystery like this is in trying to get one step ahead of the story. Mary Higgins Clark is the master of her genre. She knows it well, and instead of lapsing into predictability or letting the plot become convoluted, she expertly leads the audience through the twists and turns, allowing us just close enough to her thought process that we feel we’re on the right track, yet maintaining enough distance that we’re never quite able to see where we’re being led.

– Catherine Davis

(Simon & Schuster / $26.99 / 292 pages)

The Gods of Gotham

By 1845, many cities, including Paris, London, Philadelphia, Boston and even Richmond, Virginia, had police forces. New York, then a burgeoning metropolis growing more crowded and lawless each day, did not.

Gods of Gotham, the second novel from actress turned author Lyndsay Faye, centers on the earliest days of the NYPD, then called the “copper stars,” a reference to the crudely hammered badges pinned to their chests. Timothy Wilde, Faye’s upstanding, quick and likeable hero, is among the first of New York’s finest, but he’s a reluctant recruit – nudged into the force by his older brother, Valentine, a newly-minted police captain and strong arm for the local Democrats.

A series of truly unsettling discoveries – the corpse of a child with a cross hacked into his torso; a kinchin-mab (flash speak for child prostitute) running terrified through the streets, covered in someone’s blood – sparks Timothy’s passion for his new line of work. The discovery of a mass-grave in the forest on the outskirts of the city (now Twenty-Eighth Street) with the bodies of nineteen similarly mutilated children makes him determined to find the murderer. The case, far more than a cut-and-dried whodunit, is deeply tangled with religion and local politics: the killer is targeting Irish Catholic children from the brothels.

Faye conducted extensive research for Gods of Gotham, and it shows – in both the colorful historical details and her larger, convincing grasp of life in 1840s New York. Her portrayals of the Five Points, Battery Park, the Sixth Ward, plucky newsboys, and figures like George Washington Matsell (founder of the New York Police) are vivid and transporting, and her liberal use of flash speak, the long-forgotten idiom preferred by the criminal underclass of the era, is precise. At the same time, her attention to the dire conditions and extreme discrimination faced by the masses of Irish immigrants – an account that goes far beyond the No Irish Need Apply signs – will strike an emotional chord with Irish-American readers.

As for the mystery, Faye’s plot twists are superb. She gives you the satisfaction of implicating everyone you suspect, but in ways you never see coming.

– Sheila Langan

(Amy Einhorn Books / $25.95 / 414 pages)

Fiction:

Long Time, No See

Westmeath native Dermot Healy’s highly anticipated fourth novel Long Time, No See, revolves around the residents of a small coastal town in Northwest Ireland, and is narrated from the perspective of a young man known to neighbors as “Mister Psyche.” Recently finished with school, Mister Psyche, whose real name is Phillip, spends his days doing odd jobs around the town and running errands for his testy uncle, Joejoe.

That Healy also writes plays is obvious. He thrusts us into the world of his novel without any backstory at all, providing explanations through conversational dialogue and through the characters’ various idiosyncrasies. That Healy writes poetry is also obvious. Dialogue is not indicated by quotation marks. Instead it is woven into Mister Psyche’s narration, which has no set form. Healy purposefully makes it difficult to tell which words are Mister Psyche’s exposition, which are his internal thoughts, and which are being spoken out loud – and by whom. It’s tempting to call this technique impressionist, but scenes are so conversationally realistic – often excruciatingly so – that the result is actually closer to something out of French New Wave cinema than it is to any Monet.

The best artists use their medium to do what can’t be done in any other. Healy obviously has a deep appreciation for the novel. He shows us that it can recreate the experience of subjective day-to-day living in a way unlike any other art form. “Me body was sort of a ghost. Coming behind me,” muses Joejoe’s disembodied voice, during a blackout. “But I knew from the beginning that the mind was there.” For all its monotony, Long Time, No See is a wonderful expression of the life of a mind, in a body, in a very small town.

– Catherine Davis

(Viking / $27.95 / 438 pages)

The Cottage at Glass Beach

Nora Cunningham seems to have it all: a handsome husband who happens to be the youngest attorney general in Massachusetts, two daughters and a beautiful home. But everything is not perfect, and when her husband’s affair becomes headline news, Nora flees the press and the uncertainty of her future, returning to the place of her birth – Burke’s Island, Maine.

Nora hopes the island will be able to answer questions about her past and the mysterious disappearance of her mother, Maeve, over three decades ago. However, as time passes, the island offers more questions than answers. Were the rumors about her mother’s origins true? Did she really disappear, or did she abandon Nora and her father? And who is Owen Kavanagh – a shipwrecked fisherman or a selkie-like figure from Irish folklore, summoned by Nora’s tears falling into the sea?

The Cottage at Glass Beach is a story of rediscovering oneself, of confronting demons and of new beginnings. It is also full of Irish folklore, which you will love if you’re familiar with the myths and tales. The novel is also beset with ambiguity: what seem to be pivotal themes of the plotline slowly wisp away like the fog on the sea. For example, the question of what happened to Nora’s mother, one of the main reasons for returning to the island, is never really answered. The same goes for Owen Kavanagh – is he man or magic?

Overlooking these slight conflicts, The Cottage at Glass Beach is an enjoyable read. Barbieri’s poetic descriptions of memories and nature are exquisite. But what really wins out in the end is the unbending bond and love shared between mother and daughter despite all trials and tears.

– Michelle Meagher

(Harper Collins / $24.99 / 306 pages)

Memoir:

Call of the Lark

Reading Maura Mulligan’s deeply felt memoir, Call of the Lark, one word kept coming to mind: generous. In telling her story from childhood on her parents’ farm in Co. Mayo to her life in the U.S. with – and later without – the Franciscan nuns, Mulligan has delved fearlessly into her past. The result is a series of beautiful and honest glimpses into not only Mulligan’s journey, but also life in 1940s and ’50s rural Ireland, 1960s New York, and the experiences of young women religious during a time fraught with social change and transformations within the Church. It’s also a powerful account of the joys and strains of immigration – of finding one’s feet in a new place, but missing home and family.

The most remarkable thing about Call of the Lark – Mulligan’s first book – is her ability to both recall and gorgeously render the little details from the past that make all the difference for the reader. From the first chapter, which begins with Mulligan attending her first funeral as a new postulant (“Our laced-up, low-heeled shoes, not yet broken in, clip-clopped on the cobblestone pavement as we lined up two-by-two.”), to a more distant memory of her mother’s hands (“If there were such a thing as a blue tree, the twigs on its branches would be the veins that bulged on my mother’s chapped hands.”), her descriptive power emerges as a great strength.

Mulligan, as Call of the Lark chronicles, has worn many hats throughout her life. She can now add accomplished memoirist to her list of achievements.

– Sheila Langan

(Greenpoint Press / $20.00 / 260 pages)

Children’s Books:

Rínce: The Fairytale of Irish Dance

Where did Irish dancing come from? In Rínce, Gretchen Gannon gives the its origin a mystical spin, in a long-ago feud between the faeries and mortals of the village Rínce, named after the Irish word for dance.

The villagers and the faeries have been feuding ever since the faeries brought bad luck upon the humans in retaliation for chopping down fairy trees. In order to instill peace, King Ronan and the Fairy King Declan declared a monthly festival of dancing and merriment, which brings the two communities together. When King Declan proposes unifying the two groups even further with the wedding of his son, Finn, to King Ronan’s daughter, Delia, at the next Fairy Ring Festival, Ronan agrees, but then develops a plan to sabotage the match: if he tells Delia, a beautiful dancer, to dance with her arms straight by her sides, perhaps Finn won’t choose her as the best dancer and his future queen. But after a chance meeting between Delia and Finn before the festival, it becomes clear that the two are meant to be together. Will King Ronan’s plan spoil everything, or will it actually make Delia’s dancing even more spectacular?

With vibrant, whimsical illustrations by Don Vanderbeek, Rínce is sure to delight all young dancers and leave them even more proud of and excited about their art.

– Sheila Langan

(Outskirts Press / $20.95 / 34 pages)

Best-Loved Irish Legends

As re-told here by Eithne Massey, Best-Loved Irish Legends is a compact story-book full of tales from long, long ago, passed down from generation to generation. With language and descriptions geared towards a much younger crowd, the tales are engaging and enjoyable, with warm narratives that handle any violence or bawdiness appropriately for the age group.

The book also offers help with the pronunciation of the sometimes hard to pronounce names of the characters, which is very helpful while reading. The illustrations are vivid and charming, and wonderfully portray “The Salmon of Knowledge, How Cu Chulainn Got His Name,” “The King with Donkey’s Ears,” “Oisin” and more. It’s a quick and easy read for children who are just beginning to read by themselves and are intrigued by Ireland’s mythology. It is also perfect for story time with the little ones. And if you yourself are a just learning about these age-old tales, Best-Loved Irish Legends is a great place to start.

– Michelle Meagher

(O’Brien Press / $7.95 / 64 pages)

Leave a Reply