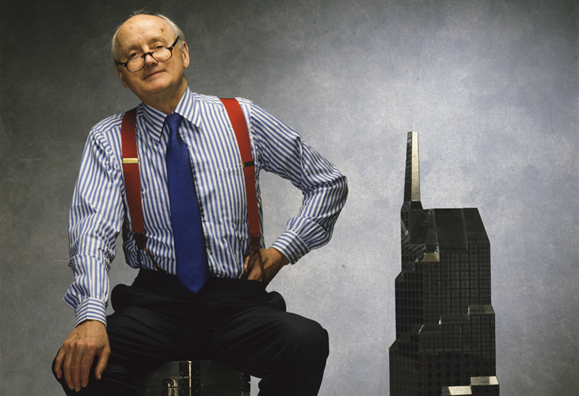

Visionary architect Kevin Roche is inducted into the Irish America Hall of Fame

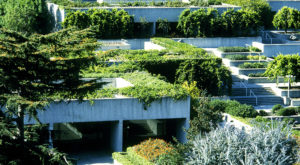

The November 1989 issue of Irish America featured an interview with Kevin Roche, the Irish-born architect famous for shaping the American landscape with his stunningly innovative buildings – corporate, educational and residential – in areas both urban and suburban. It was seven years after he had won the Pritzker Prize, the highest honor in his field, and with a career spanning over 30 years there were many key projects to reflect on, including the Ford Foundation building in New York, the skyscrapers of the U.N. Plaza, California’s Oakland Museum and the geometric Union Carbide Corporation headquarters in Danbury, CT. But, as the article’s lead indicated, Roche was also looking to the future: “In the past 30 years, Kevin Roche has established himself as one of the finest modern architects of his generation. At age 67, he had no thoughts of retirement.” “Architects never retire,” Roche confirmed.

Recently speaking over the phone from the Connecticut headquarters of Kevin Roche, John Dinkeloo and Associates, Roche laughed when reminded of this. “That was a long time ago,” he said.

In the 22 years since then he has worked prolifically, completing impressive original projects such as the Conference Center on the banks of Dublin’s Liffey, the massive Santander Headquarters in Spain and the soaring glass Shiodome in Tokyo’s city center. He has also worked on important renovations, most notably his ongoing work with the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Roche is now 90 years of age, and one gets the sense that retirement is still far from his thoughts. There is more work to be done on the Met’s Costume Institute, and designs are under way for a new Dreyfus building in Washington, D.C.

Eamonn Kevin Roche was born in Dublin on June 22, 1922 – the same month that marked the official start of the Irish Civil War. His father, Eamonn Roche, a former IRA organizer in Limerick during the War of Independence, had been a member of the first Dáil and had consequently been imprisoned in England from 1918-1920. After he returned to Ireland, he aligned himself with DeValera and the anti-treatyists, and was then jailed for two more years by the new Irish government. “He was incarcerated twice and went on hunger strike for several months. So he went through it all,” Roche recalled. “I think all of the people at that time were very extraordinary. They risked their lives and many of them were killed. They finally established the country and I think it tends to be forgotten nowadays what it took to establish the independence of the country.”

After he was released, the elder Roche moved the family to Mitchelstown, Cork, where he went on to become general manager of Mitchelstown Creamery, one of Ireland’s largest dairy and farm co-operatives. Roche attended Rockwell College in Co. Tipperary, where, he said, he wasn’t a particularly good student. “There were the honor students and then there were the middle students and then there were the barely best students and I fell into the barely best,” he chuckled.

Things certainly turned out all right for Roche. Having developed an interest in architecture, he went to study in the small architecture department at University College Dublin, after which he apprenticed with Michael Scott, who was then Ireland’s leading architect. In 1941, he received his first solo commission from his father – a piggery to house 5,000 hogs. After a brief period in London with modernist Maxwell Fry, in 1948 he decided to pursue a post-graduate degree at the Illinois Institute of Technology, under the guidance of the famous German architect Ludwig Mies Van Der Rohe. It was with Mies, whose motto was “less is more,” that Roche’s own vision as an architect began to take shape. As he said in a comprehensive 1985 interview with Francesco Dal Co, “I grew up against a very Catholic background, in which you lived constantly in fear of sin, sin which would destroy one. So one carried the burden of the imminent commission of a fatal error, making the fatal move. What Mies did was to translate this feeling into architectural terms.”

His studies at the IIT were cut short when his funds ran dry, as transferring money proved difficult in the post-war environment. After traveling to the West Coast, Roche wound up in New York, where he sought work at the massive United Nations building site. They didn’t have any openings for architects, so he worked as an office boy.

Roche hadn’t really planned on staying in America long-term, but an opportunity presented itself. He heard that the famous Eero Saarinen, son of Finnish architect Eliel Saarinen, was looking for apprentices. Jumping at the chance, Roche moved to Bloomfield Hills, MI, and began working with Saarinen on the General Motors Technical Center in nearby Warren.

As Roche explained in his ’89 interview with Irish America, his work with Saarinen would be pivotal to the course of his career and to his own architectural philosophy which, inspired by Saarinen’s approach, became more humanist. After becoming the firm’s senior design associate in 1954, he worked closely with Saarinen on such projects as St. Louis Arch, Washington, D.C.’s Dulles International Airport, and the CBS headquarters in New York.

Many of those projects were still underway in 1961 when Saarinen died suddenly, a week after a cancerous growth was discovered in his brain. Roche and John Dinkeloo, the head of production, were named the new partners of the firm, which was in the process of relocating to the East Coast at the time. They carried on, finishing Saarinen’s remaining projects before landing their first major commission as a team, the Oakland Museum in California. They started their own firm, Kevin Roche, John Dinkeloo and Associates in 1966. They worked fruitfully together on many prominent commissions that included the Ford Foundation headquarters in New York and the National Aquarium D.C., until Dinkeloo’s death in 1981.

Since then, Roche has been the visionary behind such buildings as the Nations Bank Plaza – the tallest building in Atlanta – the Museum of Jewish Heritage in downtown Manhattan and its moving Holocaust Memorial, and New York University’s Kimmel Center for University Life. When told that I had recently been inside that very building, he asked “And were there students sitting on the steps?” There had been. “Well, that’s what we wanted them to do. It’s funny how people actually love to sit on them. We got that at the Met too, people love to sit on those steps,” he said, referring to what are some of the most sat-upon steps in all of New York City.

His interest in that seemingly minute detail of how his design is being enjoyed, long after his part is essentially over, sums up one of the most interesting things about Roche’s work – the heightened awareness he has, whether he is designing a corporate complex or renovating a museum wing, for the way people move throughout a space, how they react to and interact with it. His buildings are modern and innovative, but his vision for them is inspired by the idea of community.

“I’ve always been very much interested in the natural environment and the effect it has on our lives. In the architecture we try to always introduce that in some form or another. I think people like to establish a community because humans need that. I think they feel they need to belong to something. It’s the idea of the village. Not that I’d necessarily want to live in a village,” he quickly added. “That doesn’t always happen in a village, but that’s the idea.”

Roche and his wife of 49 years, Jane (née Touhy) with whom he has five children and thirteen grandchildren, live in Connecticut, “in an old house surrounded by trees.” They spend many weekends in New York City, where they have “a little apartment and try to catch up on everything that’s going on.” In the same way that he is adept at working in environments both natural and urban, Roche enjoys moving between the two. “Each one has its own virtues and its own advantages and I think that being able to move from one to the other is the ideal situation,” he said.

His advice for aspiring young architects, though he knows they face a different time and different challenges than he did when he was starting out, is that “it comes down to a lot of luck, but one thing you’ve got to do is work, work, work. All my life I worked 6 or 7 days a week, 8 or 10 hours a day. You have to do that and keep at it.”

It’s impossible to say whether Roche’s life and career would have taken the same course had he not come to the U.S. In any case, it seems that being on uncertain terrain was one of the things that propelled him forward. “One of the advantages of being an immigrant is that you’re thrown into the fire and you have to fight your way around, whereas if you’re sitting at home you don’t have to do that.”

He still occasionally returns to Ireland both for work and to see family. And though he calls himself more or less a mix of the two cultures, his love of America and the charge it gives him are clear. “We’re all very lucky to be here,” he said. “It’s wonderful being Irish but it’s

wonderful being here, it’s been a great country to live and work in. The opportunities are still here and there are many, many things that can happen here that we can help to evolve. It’s always on the go, it’s always happening, and you’re never looking back, you’re looking forward to getting on with things. I really don’t like to adhere too much to the idea of looking back and saying ‘I belong to something else.’ I like to look forward, and I have great hope for the future here.”

See photographs of Kevin Roche’s buildings:

I’m impressed by what you have accomplished! So poud of it as well!I love to read about how far the Irish have reached…..

Your Mom would be so happy!