Jack Donovan Foley, the American grandson of Irish immigrants, invented “foley art,” a sound-effects technique still used in films today – so subtle and perfect that viewers don’t notice anything has been added.

Something was not quite right on the stage of Alice Tully Hall at New York City’s Lincoln Center one night last September. It was the U.S. premiere of the recently restored Irish silent film, Guests of the Nation, and the RTE Concert Orchestra, on stage to accompany the film, was getting into place in front of the movie screen. Woodwinds, percussion, brass, all ready to tune up. But who were those strange people in long white coats, and what were the bizarre mechanical contraptions they were assembling right next to the violins?

Emcee Gabriel Byrne, the actor and Cultural Ambassador of Ireland, cleared up the mystery. They were “foley artists,” he explained, the veritable magicians who create the sound effects we hear in films and television. They got that name because in the 1920s an enterprising Irish-American named Jack Donovan Foley figured out that the most efficient and effective way to enhance the audio in films was to make the sounds himself.

The crew at Alice Tully Hall that night used their peculiar instruments to deliver a delightful live soundtrack of squeaks, crashes and squeals to The Lactating Automaton, a 2011 silent short by Irish filmmaker Andrew Legge, which the Irish Film Institute screened before the main feature, Guests of the Nation.

The foley artists on stage waved, banged and twirled their noisemakers while the main character in Legge’s whimsical film, a mechanical woman raising a human child, creaked and clanged across the screen. But as the film progressed, their frenetic activity gradually evaporated into the totality of the film, and even though they were still making their noises on the stage right below the screen, they effectively disappeared.

That is just as it should be. When done correctly, foley is undetectable. Although Jack Foley worked in cinema for 40 years, his name never appeared in any film’s credits. Audiences were not supposed to notice his handiwork or realize that the sounds they heard in movies of clinking glasses, swishing skirts or flapping bird wings were anything but real.

We still accept the added sounds in film and television as implicitly authentic, even if we really know they are not, just as we pretend that the beeps and whirrs from our technological gadgets are actually connected to their functions. We live in a world of created sound, and we are glad to play along with the illusion, especially at the movies, allowing ourselves to be fooled for the sake of the narrative.

“Even sophisticated audiences rarely notice the soundtrack,” said film sound expert Elisabeth Weis in Cineaste, “Therefore it can speak to us emotionally and almost subconsciously put us in touch with a screen character.” Raised by a mother well known for her yarns, Jack Foley understood the power of feelings in telling a story.

In the beginning, foley art was all about footsteps and the sounds of clothing. Jack and his crew “walked” thousands of miles in place on small patches of dirt or gravel in a post-production studio, eyes glued to the screen in front of them as they imitated the film characters’ gaits and used the pieces of cloth in their pockets to simulate the rustle of a pair of pants or the crinkle of a shirtsleeve. It wasn’t enough just to match the footfalls and movement of clothing, Jack wanted to reproduce the personalities of characters, to become them, and let the sound of their tread augment the story.

He created footsteps and body movement sounds for stars like Laurence Olivier, Charles Laughton, Kim Novak, and Sandra Dee. He said Rock Hudson had “deliberate” footsteps, James Cagney’s were “clipped” and Marlon Brando’s were “soft.” As with other sound effects, like slamming doors, broken glass, or falling bodies, Jack and his crew would strive to create the perfect sound that fit the character’s personality and the nuances of the scene. The foley crew were not just noise makers, they were actual performers.

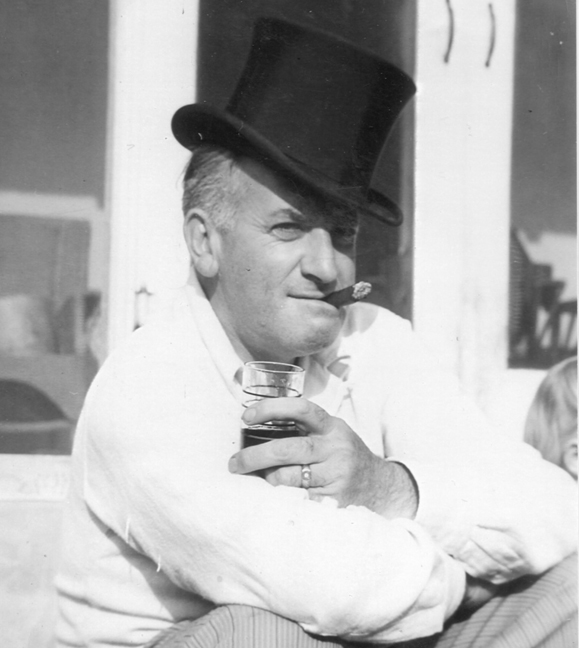

“Foley artist,” if it appears at all, is one of those job titles in movie credits like “gaffer” or “key grip” or “best boy” that few people understand, but like those other jobs, it is essential to the completed artistry of the film. Today, foley artists work closely with new technology like ProTools software, but their real skills lie in physical agility and perfect timing (many are former dancers), as well as in a kind of glee in the bounteous joys of making noise. According to his granddaughter, Catherine Clark, Jack Foley was full of fun and loved the challenge of thinking up new ways to reproduce sound.

“On Sundays after Mass, our kitchen became a sound stage,” she recalled. “My grandfather and the kids would be playing around with all sorts of things from the house trying out different effects on the table.”

While some silent films had sound before Foley’s time, from live performers and recorded effects, he was the godfather of the post-production method that allowed a crew to physically create spot effects, match them to the action on screen, and record it all on one reel. He didn’t invent sound effects in film, but he did develop the best way to make them work.

Foley art has always been vital because microphones on a movie set are primed to pick up actor’s voices, and therefore do not adequately record incidental sounds like the pages turning in a book, or silverware tapping on china. Also, location shooting can involve unwanted background noise, so the sounds of wagon wheels and fallen garbage cans need to be added after the shoot is completed. Pre-recorded sound effects can be useful, but they do not always match the particular ambience of a given scene.

Caoimhe Doyle, the Irish foley artist who led the white-coated crew at Alice Tully Hall, explained in the journal Irish Film why foley is best for many sounds “like the kisses and the punches.” She said that, while those effects can be found in CD libraries, pre-recordings “don’t always work because we as humans act so, well, randomly.” Foley effects can be so lifelike that no one would ever suspect how they are actually created. Doyle claimed “every car chase you have ever seen” gets its squealing tire sounds from a hot water bottle being dragged across damp kitchen floor tiles.

Like today’s professionals in the field that bears his name, Jack Donovan Foley knew how to work hard and, even more importantly, how to improvise and be flexible. Over his lifetime, he was an accountant, a cartoonist, a stunt man and movie double, a semipro baseball player, a film director, a writer and an oil painter – in addition to pioneering the field of sound effects in film. Bred with the resourcefulness of immigrant stock, he was not afraid to quit his job at the Bell Telephone Company in his early twenties, pack up his family and move from New York City to the California desert to find a new home.

In 1927 his employer, Universal Pictures, was facing stiff competition from Warner Bros.’ The Jazz Singer, which featured characters speaking dialogue and singing. Not to be outdone, Universal scrambled to retrofit its already completed version of the stage musical Show Boat with sound. Using borrowed audio recording equipment, an orchestra was set to play the score as the musicians watched the movie on a screen. It was Foley, then an assistant director, who assembled a team to add incidental sounds like clapping or cheering to be recorded at the same time. The “direct to picture” technique was born, and other studios brought their films to Universal for similar post-production treatment.

No one had planned or “workshopped” this technique; it was forged out of necessity, almost on the spot. In its early years, the motion picture business was not organized in the way it is now. There were few job titles with specific responsibilities, so everyone did whatever was needed to get a film made. Foley wrote in the Universal Studio Club News that a call had gone out for employees with “any knowledge of radio” to help with the recording work on Show Boat. Claiming his “short stint with the telephone company” as radio experience, Jack dived into the unknown. According to Vanessa Theme Ament in The Foley Grail: The Art of Performing Sound for Film, Games and Animation, the industry was “being reinvented on a daily basis,” and was perfect for people “with ‘gumption’ and ingenuity” like Jack.

Foley was born in 1891 in the Yorkville section of New York City to the children of Irish immigrants. His father, Michael, whose family came from the Dingle peninsula in County Kerry, worked on the docks and as a volunteer fireman, and wrote songs that he sang at a local pub. Soaked to the skin while fighting a warehouse fire, Michael died of pneumonia when Jack was a baby. His mother, born Margaret Donovan, lived with her widowed father and four sisters on East 82nd Street, until she married Michael Gilmartin, the son of Sligo immigrants, when Jack was 16.

Foley worked as a clerk on the docks before joining the phone company, but he lived for baseball. Thinking that the weather in California would be more suitable to the pursuit of his favorite sport, he moved there in 1914 with his wife, Beatrice Rehm, a championship ocean swimmer, who shared his love of athletics. Because Foley was a Catholic and she was a Protestant, they married in secret, but by 1920 he was the sole support for both their families. All 11 of them, including both sets of in-laws, lived with Jack and Bea in California.

They settled in Bishop, 300 miles north of Hollywood, where Jack had a job during World War I guarding natural resources from possible foreign sabotage. He also worked for a hardware store, wrote and drew cartoons for the local paper, and was active in the Bishop theater group, where he wrote some plays. When farmers near Bishop sold their land to supply the rapidly expanding city of Los Angeles with water, revenue began disappearing in the town. Foley contacted friends in the film industry to persuade studios to use the area around Bishop to shoot westerns. The town received needed income and he got a job as a location scout.

In 1923, an advertisement for a movie he co-wrote and co-directed, How to Handle Women, claimed that Foley had “successfully crashed the gates of Hollywood without any ‘pull’ other than his own ability, inclination and perseverance.” He scripted other films, but after Show Boat, put all of his efforts into the new horizons of sound, even enrolling at the University of Southern California to learn more about it.

In 1929, he voiced the first “Tarzan yell” on film in Tarzan the Tiger, with Frank Merrill. It was a hearty “EEE-Yawh” which he said was modeled on the coaching style of Detroit Tigers’ baseball manager Hughey Jennings. In 1959, according to TV and movie soundman Jim Troutman in an RTE radio documentary about Foley, Stanley Kubrick was ready to send the cast and crew of Spartacus back to Spain to re-shoot a battle scene because he didn’t like the sound of the soldiers’ footsteps. Jack got the job done by shaking a few handfuls of keys on rings in front of the microphone. Voila! There were the Roman legions with their armor and spears tramping into battle.

Cathi Clark said the film industry began using her grandfather’s name to designate the art of adding sound effects to film after people he had worked with at Universal spread out to jobs at other studios. Foley had a deep affection for the people he worked with, and Clark said his former crews honored him by referring to the process he developed as “making foley.” Before long, they became known as “foley walkers.” “Foley” stages now appear on movie lots everywhere, like the new one at Skywalker Sound, George Lucas’s facility north of San Francisco.

Even though he was never an editor, the Motion Picture Sound Editors named Jack Foley an honorary member at a dinner in 1962. (“The Irish Washerwoman” played as he walked to the podium, and he stopped everything to dance a little jig.) In 1997, a Lifetime Achievement Award was presented posthumously to Clark by the MPSE at its Golden Reel Awards Dinner. In 2000, a National Public Radio production, Jack Foley: Feet to the Stars, won a George Foster Peabody Award and RTE recorded another radio documentary on Foley in Ireland. An Irish film about him and his family connections in Dingle had been in the works, but was shelved in 2008 by the economic downturn and the sudden death of one its developers, Chips Chipperfield – a 1996 Grammy winner for The Beatles’ Anthology documentary.

A longtime friend, actress Mae Clarke – who got a grapefruit shoved into her face by James Cagney in 1931’s Public Enemy – believed that Jack never got the recognition he deserved. Still, his favorite spot was not on the dais at a fancy awards dinner. He much preferred to sit on a bench outside the Universal commissary, talking to people as they came and went, harvesting material for his column and cartoons in the Universal Studio Club News, which he wrote under the name of Joe Hyde, a studio janitor. Foley, who died in 1967, was a shy, unassuming man who, his granddaughter says, would be embarrassed by any adulation, but pleased to know that his namesake field is flourishing.

“Foley is far from a dying craft,” said Caoimhe Doyle, whose lengthy résumé of film and TV assignments backs up that claim. In addition to feature films and television, demand has mushroomed from computer generated animation projects and films dubbed for foreign markets, which require lots of post-production sound.

Nominated for an Emmy as part of the sound team on the 2011 HBO series Game of Thrones from Ireland’s Ardmore Studios, Doyle has created sound on films like The Guard (2011), The Men Who Stare at Goats (2009) and Knocked Up (2007). She echoed Jack Foley’s philosophy that a character’s feelings have to be “transcended into the sound of footsteps.”

“The picture will tell you what is going on,” she said in an interview about Game of Thrones on The Irish Film and Television Network website, “but sound tells you how to feel about what is going on. It’s a subtle but very persuasive tool for the director.”

Doyle, who learned her craft from Andy Malcolm and his team at Footsteps Post-Production Sound Inc. in Ontario, praised the foley facilities at Ardmore, near Dublin in Bray, County Wicklow, which were purpose-built to accommodate sounds in scenes from wide-open plains to intimate interiors.

“The room is designed to record really minute, detailed sounds – skin touches, and very subtle stuff as well as explosions and big stuff like that – we can do the full range.”

Doyle was an assistant film editor before she became a foley artist, and she said the only way to learn how to do it is on the job working with an experienced foley practitioner, almost like a medieval craft passed down through generations. Every foley artist becomes a garbage-picker, constantly on the lookout for stray objects that might produce just the perfect sound for a character or scene, and a foley prop room looks like a junkyard. Foley artists all have their own “bag of tricks,” filled with their favorite noisemakers. Doyle said her constant companion is a piece of chamois cloth, the kind you use to wash your car.

“We’ve delivered babies, amputated legs, heads and all sorts with the chamois. It is also good for cooking and even wet fish. I would say that we have used it once on every film I have ever worked on.”

As she told Film Ireland, technology has given foley editors great flexibility to manipulate sound effects, but foley is still done “in the same way it has been performed since the 1930s when Jack Foley first did it: we stand in front of the microphone and watch the screen and do it when the actor does it.”

Foley’s work, his meticulous synchronization of sound to action and emotion, has seeped into our communal consciousness, and those made-up sounds can be as real to us as physical objects. When actor Ewan McGregor first picked up a Jedi weapon on the Star Wars set, he couldn’t stop himself from making vocal sounds as he waved it about – the same sounds made by a foley artist in the earlier films in the series that McGregor had internalized as a boy. Director Lucas approached him, “Ewan, don’t worry about making that sound, we have enough money to create it in post-production.”

Now, that’s a story Jack would have loved.

The art of foley presented live:

Links to more information:

Conan O’Brien cavorting on the Foley Stage at Universal Studios

NPR’s “Jack Foley: Feet to the Stars”

The RTE radio documentary “Foley”

In addition to Vanessa Theme Ament’s book, The Foley Grail: The Art of Performing Sound for Film, Games and Animation (Burlington, MA and Oxford, UK: Focal Press, 2009), another good source on foley is David Lewis Yewdall, Practical Art of Motion Picture Sound, (Waltham, MA and Oxford, UK: Focal Press, 2011).

Hello, Jack Foley was my Great Uncle. I just heard from a family friend about this article and he said there’s a picture in the print version of Jack and his two nieces. Those nieces are my mother and her twin sister. Any chance I could see that photo? Thanks so much. -Mary

Hi Mary,

Would you happen to kn0w if any of Jack Foley’s relatives are still alive in Ireland?

This is in relation to a book about Jack which is soon to be published.

Thanks Eddie

Hello Mary,

Hope you’re well.

Just a quick hello and how wonderful it was what your Great Uncle did for the film industry. I’m currently a full time mature student, studying Visual effects/post production and are currently writing up the important works of the great Jack Foley… In fact I’m even contemplating a career as a foley artist.

Take care now

Michelle (UK)

Hi there,

Could you email me? I am researching Jack Foley. Thanks

I was just thinking about my grandpa today.

I am searching for a possible connection to Jack d Foley as I am in the music and sound industry. My family came from Co Claire, Eire and immigrated to ILL. Last ancestor in my family tree is Malaher Foley. Has your family traced your ancestry? If you have information I would be grateful to find myself in your family tree.

Thank you for your time and interest.

Dennis Lyle Foley

Loved my grandpa and all his stories he told us

Wow, we’re worse than the Chinese. We’re everywhere, from that little emerald pearl in the ocean, with leprechauns and all.

Tagus dut,

Peadar