The Way is a movie about a father and son, written and directed by Emilio Estevez and starring his real-life father, Martin Sheen.

The Way, a modern-day road film rooted in the past, is a heartwarming story of redemption and renewal with a message that it’s never too late to change.

Tom (Martin Sheen), an American doctor, travels to St. Jean Pied de Port to collect the body of his son Daniel (Emilio Estevez) who has died in a storm in the Pyrenees. Rather than return home, Tom decides to complete the journey his son began and sets out to walk “The Way,” the centuries-old pilgrimage route, some 500 km (depending on where you start) to the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela, which legend holds is the burial site of St. James the Apostle.

Along the route, from the south Pyrenees through Galicia, to the west coast of Spain, Tom meets a trio of characters all motivated by different goals: Jack (James Nesbitt) an Irish travel writer, is looking to cure his writer’s block. Sarah (Deborah Kara Unger), a testy Canadian, is recovering from a bad break-up, and the jovial Joost (Yorick van Wageningen) from Holland is trying to lose weight.

The scenery of the Galician countryside is stunning, as is the performance by Sheen who found fame in such early movies as The Badlands (1973) and Apocalypse Now (1979), and whom younger generations came to know as President Bartlet in TV’s The West Wing (1999-2006).

The making of the movie was a personal journey for Sheen, now 70, the American son of immigrant parents, a Galician father Francisco Estevez, and an Irish mother Mary Ann Phelan from Co. Tipperary.

When we spoke in October, he, Emilio, and several other family members had been touring the U.S. in an old U2 tour bus to promote the movie, and New York was just one of many stops along the way.

When did you first think about walking the Camino de Santiago?

We started the journey in the summer of 2003 with a family reunion in Ireland. My mother was from Borrisokane in North Tipperary, so we gathered in that village on May 22, 2003, to honor my mother’s 100th birthday. She had died in ’51 of course, but we had gone to enough funerals and so we decided we were going to have a celebration. All the remaining siblings gathered and we had a special Mass for my mother and a wonderful three-day celebration at which I invited everyone to come to Spain to walk the Camino with me. I only got two takers – my grandson, Taylor, who was kind of stuck with me because he had been my assistant on The West Wing, and Matt Clarke, who played the priest in the film who gave me the rosary. So the three of us went off to Spain and we tried to figure out how to do the Camino in the remaining two weeks of vacation I had left and it was impossible, of course. So we rented a car and drove the Camino and when we got to Burgos we stayed in a country B&B they call a Casa Rurale. We took rooms there for the night and they invited us to the pilgrim supper. At that supper, the family was serving, and their youngest daughter, Julia, took a look at my grandson Taylor and he looked at her. They’ve been looking at each other ever since. They’re married and they live in Burgos. So that was the first miracle. In fact, her mother’s name is Milagros, which means miracle in Spanish. So that was the start of the whole adventure.

I love that it started in Ireland because a lot of Irish people do that pilgrimage.

Yes, there’s the Society of St. James and they’ve been a great supporter of the film. They gather as you know, to begin pilgrimage from Ireland at the gate of St. James, which is at Guinness.

You know what, this summer we got a personal handwritten letter from Mary McAleese who was writing to say she had just seen the film with her daughter and she wanted us to know that her daughter was preparing to leave for the Camino as she was writing the letter. And she was thanking us. So it doesn’t get any more satisfying than that.

At the beginning of the film, Daniel says that life isn’t something that you choose but that you live.

Yeah, I think Emilio was trying to say that we’ve got to loosen ourselves from a fixed focus in our lives. We have to be more imaginative. And it’s when we trust that our feet will land on firm ground if we’re going into a strange area, that’s when we can really grow.

From an Irish point of view, I was touched by Jimmy Nesbitt’s performance and the mention of the church in Ireland and how it’s become “a temple of tears.” But yet we see Jimmy go into the cathedral at Compostela.

Yes, he has a transcendent moment. That’s my favorite sequence in the whole film because each one of us, individually, is brought to ourselves – a realization of the mystery of what we are, who we are, and what is possible – and there’s not a word spoken. It’s the most powerful and most mysterious scene in the film. Over and over again during our cross-country tour because we go in to do Q&A after the film, we go in usually during that scene and the audience’s response, pretty much nationwide, has been one of great joy. Many people weep out of joy during that sequence. It is just a very deeply mysterious moment that we never counted on when we were filming it. We didn’t quite know what we had, you know.

Could you talk about your view of the afterlife?

Well you know, I’ve had a view on the afterlife but I heard Richard Rohr, an American Franciscan Friar who is a theologian as well, and he said, one of my favorite quotes that I love repeating: “You know we don’t go to heaven, we become heaven.” And that I think is a very insightful message about the afterlife. The afterlife is the before life. It’s here. It’s now. We’re not invited to live outside the flesh. But our effort is to unite the will of the flesh to the work of the flesh. Then we’re going to be balanced and focused and the afterlife will take care of itself if we take care of this half. The afterlife is really none of our business. If we’re focused on the business of what our lives are about, then the afterlife will be absolutely fine. Another thought about that is, that we don’t know what God is, do we? A major question, you know. Most of the time when I ask that question I get an answer that confirms what God is not because it’s coming from another human being we’re all very finite creatures and we very often, unfortunately, reduce God to our size. And the genius of God is choosing to dwell within us despite ourselves.

So the scandals with the Catholic Church, how has it affected you?

It’s a drag but it’s a confirmation that the Church is fallible, it’s human, most of it is run by men and they’re very limited. It’s a very very clear message that the Church is not God. It can be the conduit to God, but we have to find forgiveness and strength in our communities. The Church is not the faith, but the Church is responsible in large measure for the faith. Dorothy Day – when the Church was being criticized – said, “We have to remember that the Church is the cross that Jesus chose to be crucified on. He didn’t choose theologians for disciples. He never blamed them for being human. On the contrary, he celebrated their humanity and assured us that’s where God chooses to dwell.”

I read that Day had a big influence on your life when you first came to New York.

Oh yes, very much so. You know, my friends at the Living Theater, which was the first theater that I worked at in New York, Julian Beck and Judith Molina were my heroes and they hired me as a curtain puller and an understudy. They didn’t have a whole lot of money, so they said to me “we have a friend downtown who has a breadline. You can go down there and get a free supper every day and you don’t have to listen to a sermon and you don’t have to pay a penny.” So I started going down there, and the place of course was the Catholic Worker and their friend was Dorothy Day. I was asked recently if I had met Dorothy Day and I can’t honestly say I did because I didn’t have a clue who she was or what the organization was. I was there because I was a starving actor, literally, and that’s where I ate most of my meals. I remember one day asking the people there if I could be of assistance to them because they were so generous and they said to me, “You can help us fold the newspapers this weekend” and I said, “You have a newspaper?” And they said, “Of course, it’s called the Catholic Worker.” So go figure. And to this day, I can’t tell you if I met Dorothy Day. But it’s not important because her life and her work are what still inspire me, and gladly so.

Can you talk about the U.S. road trip?

Three of the most rewarding stops were the University of Notre Dame, Ann Arbor at the University of Michigan, and Virginia Tech—which was not on our schedule. We were invited to come via the internet. They started an Internet plea with Emilio to detour the bus from Atlanta to stop at Virginia Tech on the way to DC, and we made that trip and gladly so. It was the most extraordinary place. We decided to go because our film, in large measure, is about healing. There’s not a better example in our country of that than Virginia Tech after that awful massacre there a few years ago. So they were a great source of nourishment and confirmation for us and our film, and one of the high points of our whole journey. We’re now in our 26th city. We’ve been from San Francisco to New York to Miami to Ohio and Minneapolis and so many wonderful places in between. The reaction to the film has been so deeply gratifying, and nowhere more so than Virginia Tech.

And has [the road trip] also renewed your faith in America?

Yes, very much so. The country is going through a lot of great difficulties, and a lot of loss. There’s a lot of healing that needs to get done. There’s a lot of anger and a lot of resentment, and rightly so. People have had a lot of their savings ripped away. They’ve lost houses and cars and a lot of possessions and so they’re frightened and insecure. And yet there’s something else going on that we’ve experienced, and that is a great resurgence of community. People are coming together and families are being forced to live under the same roof, and a lot of great good is coming out of that because they’re beginning to realize what’s important. Food banks around the country have never had more needy people on line, and yet there’s a great sense of community and family that maybe wouldn’t have happened without this great difficulty. So as usual, it takes great suffering to realize great healing and great faith, and that I see going on far more than anything else.

I think the same is happening in Ireland. I know you just did a film over there.

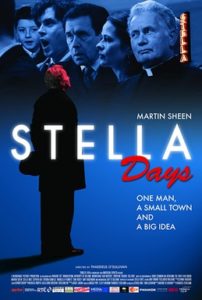

Yes, I did a film about a priest in my mother’s village, as a matter of fact, who built the first cinema in Ireland back in the 50s. The film is called Stella Days. So I got an opportunity to play a padre and it was great, I loved it. I just returned this summer to do a segment of Who Do You Think You Are? – the heritage show – and that’ll air in February. So they took me to Spain and Ireland.

[…] Concannon winery in Livermore, California and discovering an Aran Island connection ; talking to Martin Sheen about his new movie The Way, a really inspirational film that set me on the road to physical […]