Irish Sculptors Led the Way in Celebrating Civil War Heroes

Magnificent in bearing, you find our nation’s unabashed heroes in Central Park and Lincoln Park, Boston Common and the National Mall. Still others stand like sedentary sentinels in village greens, public buildings and parks from Maine to Louisiana.

Civil War monuments dot the American landscape, bronzed warriors turned green, oxidized by age and neglect, having battled the elements for six generations. They are the survivors of history and touchstones to our past.

While public art has shaped our memory of the Civil War since the 19th century, much of the visual depiction of the war – from generals to foot soldiers – was created by an amazing group of Irish-American sculptors, several of whose families came to America to escape the Irish Famine.

Dublin-born sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens, and his brother Louis, born in New York; the five Milmore brothers from County Sligo; Launt Thompson from County Laois; and American-born artists William R. O’Donovan and James E. Kelly are a few of the Irish-Americans whose work deserves to be appreciated as part of the Civil War commemoration now taking place.

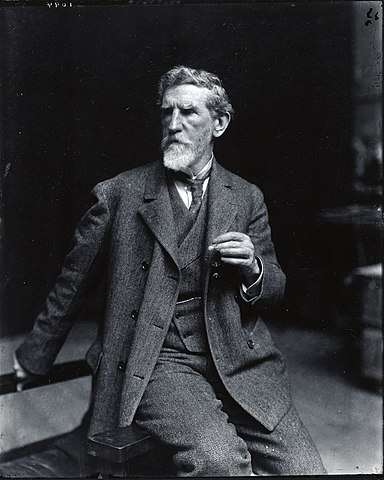

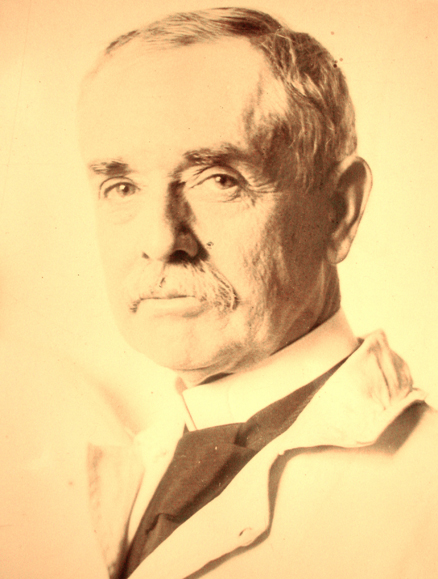

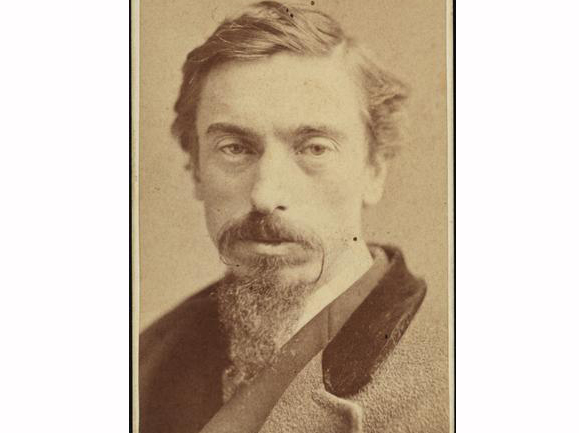

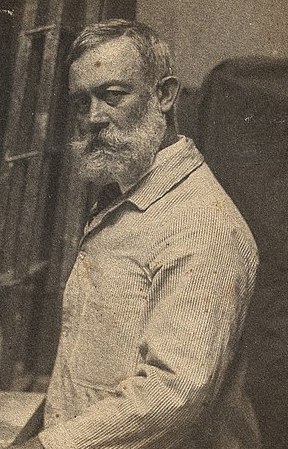

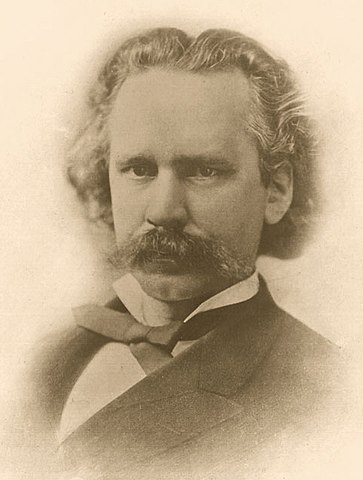

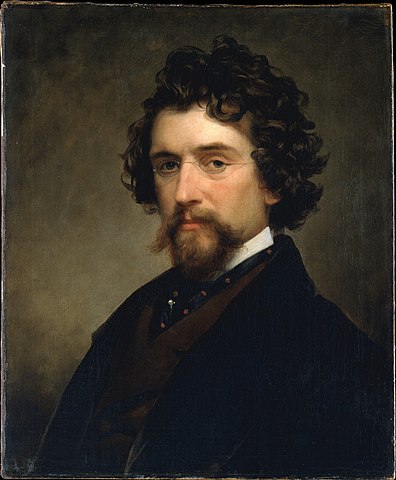

Bottom row: William R. O’Donovan by Thomas Eakins, Martin Milmore, Matthew Brady

Artistic Expression in America

It may seem curious that Irish immigrants of modest means and education became artistic interpreters of America’s defining moment. After all, sculpture required a period of study and apprenticeship that was not available in Ireland, except to the wealthy.

But America gave the immigrant Irish a freedom of expression that Ireland hadn’t offered, and many Irish transformed their native intelligence into creativity by combining classical traditions of sculpture with new indigenous themes of American life, producing a stunning canon of public art.

“The versatile Irish have found in America a favorable field for artistic development; transplanted to this spacious land not a few of the race have revealed an unusual gift for sculptural expression,” art historian Lorado Taft noted.

The Irish had a long tradition of patriotism toward their adopted homeland dating from the Revolutionary War, and many were eager to espouse the democratic ideals of equality and justice which were at the heart of the Civil War conflict.

In addition, Irish sensibilities were shaped by centuries-long acrimony with Britain and imbued with the notions of valor, honor, suffering and death that war imparted. While Irish artists captured the power and the glory inherent in battle, they also revealed the humanity and bravery of those who did the actual fighting, particularly the foot soldier.

Augustus Saint-Gaudens

Symphony in Bronze

The most acclaimed artist of the Civil War, and indeed, American sculptor of the 19th century, was Augustus Saint-Gaudens (1848-1907). He was born in Dublin on March 1, 1848 to a French father and Irish mother, Mary McGuinness of Longford. The family fled the famine and arrived in Boston that September, before eventually moving to New York City. Augustus apprenticed as a cameo cutter and took classes at the Cooper Union, then moved to Paris as a teenager to study at Ecole des Beaux-Arts, followed by a stint in Rome.

Saint-Gaudens’ first major work, a sculpture of Admiral David Glasgow Farragut, was unveiled at Madison Square Garden in 1881, and hailed as “a combination of realism and allegory” that set him apart from his peers.

Other commissions quickly followed, including the General William T. Sherman Monument in Central Park and General John A. Logan in Chicago’s Grant Park. He also completed two significant portrayals of President Abraham Lincoln in Grant Park and Lincoln Park in Chicago. He created over 150 sculptures in his lifetime.

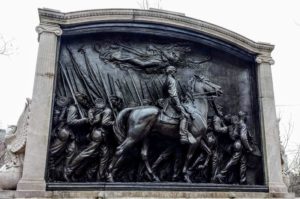

Saint-Gaudens’ most celebrated work is the Colonel Robert Gould Shaw Memorial on Boston Common. A tribute to Boston’s 54th all-Black Infantry Regiment, whose valor was captured in the film Glory, the memorial took fourteen years to complete. The perfectionist artist approached the project painstakingly, hiring forty black men as models, from which he chose sixteen to appear in the final work.

Gregory C. Schwarz of the Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site in Cornish, NH, writes that “After declaring the sculpture complete in October 1896,” Saint-Gaudens heard from French sculptor Paul Bion, “whose opinion he valued. Bion was critical of the angel and this threw Saint-Gaudens into a panic. While the rest of the sculpture (went) to the foundry, he withheld the angel for three months and reworked it.”

The memorial was finally unveiled in May, 1897 at a ceremony attended by Booker T. Washington, philosopher William James, and families of the soldiers. It was

described by one art critic as “a symphony in bronze,” that captured the humanity, nobility and utter idealism inherent in the war.

Collaborating with Augustus throughout his career was his brother, Louis Saint-Gaudens (1854-1913), an outstanding sculptor

in his own right who created an important body of religious and classical works.

Louis’ signature Civil War sculpture is the monument to the 2nd and the 20th Massachusetts Volunteer infantry regiments. The monument features a pair of marble lions carved out of single blocks of unpolished Sienna marble, and sits resplendent in the foyer of Boston Public Library’s McKim Building.

Martin Milmore

Honoring the Unsung Hero

In 1851, recently widowed Sarah Milmore of County Sligo emigrated to Boston with her five young sons. The boys began working when they were barely teenagers. Charles and Patrick apprenticed to a cabinetmaker, and Joseph and James worked for monument maker John Foote. Martin, whose artistic genius was noticed at the Brimmer School in Boston, talked his way into working for well-known sculptor George Ball, by offering to sweep the studio floor.

Martin’s apprenticeship with Ball led to several commissions of classical works, followed by the Roxbury Civil War Soldier at Forest Hills Cemetery in Jamaica Plain, a commission he received at age 21. It depicts a Union soldier leaning on his rifle, staring out over the cemetery.

The Boston Evening Transcript wrote, “The young soldier is in a reverie over the graves of his comrades. It tells the story of what it costs to preserve for us our Union, our justice, our freedom and our humanity.”

Milmore’s Roxbury Soldier helped to usher in a new era of public sculpture, described as “un-heroic and introspective,” depicting soldiers and sailors rather than generals and admirals. It marked a significant new direction in American sculpture that was more in tune with democratic principles than to the military hierarchies that art traditionally portrayed. Milmore’s foot soldiers and sailors could have been anyone’s sons, and it gave his work tremendous popular appeal.

The Roxbury Soldier resulted in so many commissions that Martin and his brothers opened a studio on Harrison Avenue in Boston’s South End and began fulfilling orders for dozens of towns and villages throughout the region.

The Milmore studio produced Civil War statues allegorical in nature too. The most exotic is the Sphinx Memorial at Mt. Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, carved by Joseph Milmore and commissioned by Dr. Jacob Bigelow, an enthusiast of Egyptology. The six foot, marble Weeping Lion at Colby College in Waterville, Maine, a tribute to the 25 college students and alumni who died in the war, was carved by James Milmore, according to art historian Ernest Rohdenburg III.

Martin Milmore’s greatest work is the Soldiers and Sailors Monument on Boston Common, unveiled before 100,000 spectators and 25,000 veterans in September 1877. The monument was meant to solidify the union between the North and the South in the tense era of post-war Reconstruction.

“There is nothing of haughtiness nor defiance in attitude or expression,” notes the official program from the dedication. “(It) does not symbolize America the conqueror, proud in her strength and defiant of her foes, but rather America the mourner, paying proud tribute to her loyal dead, whose bones lie upon every battlefield of the great South, toward which her face is turned.”

Launt Thompson

Acknowledged Genius

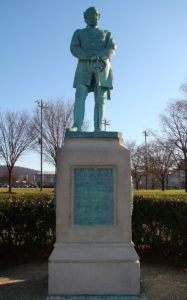

Launt Thompson (1833-1894) of Abbeyleix, County Laois was also part of the Irish Famine exodus, arriving with his widowed mother in 1847 and settling near Albany. He had a natural talent for drawing and visualization, and apprenticed with Erastus D. Palmer for nine years, working on portrait busts and medallions before graduating to full-figured sculptures.

Thompson received several Civil War commissions, including The Color Bearer (above), which honors the fallen soldiers of Pittsfield, MA, plus statues of General Ambrose Burnside in Providence and General John Sedgwick at West Point.

The Pittsfield committee described Thompson as “an artist of distinguished reputation and acknowledged genius, so original in thought, so striking and appropriate in character.”

William R. O’Donovan

The Rebel Artist

American-born artist William Rudolf O’Donovan (1844-1920) was born in Preston County, Virginia (now West Virginia) to an Irish father and German mother.

According to Civil War writer T.L. Murphy, author of Kelly’s Heroes: The Irish Brigade at Gettysburg, O’Donovan “enlisted at age 17 in 1861, and served in the Confederate Army from 1st Bull Run to Appomattox.”

O’Donovan created the highly regarded Sailors and Soldiers Memorial in Lawrence, MA, unveiled in 1881, and statues of President Lincoln and General Grant at the Soldiers and Sailors Arch at Prospect Park in Brooklyn, NY, unveiled in 1895.

Ironically, this former Confederate soldier won the commission for the New York Irish Brigade Monument, considered one of the most moving memorials at Gettysburg. Unveiled in 1888, it features a Celtic Cross with traditional symbols, and a mourning Irish wolfhound at the base, meant to signify devotion to duty.

O’Donovan’s Confederate Memorial in Wilmington, NC, which depicts a single soldier at rest, looking over a graveyard, is similar in nature to Milmore’s Roxbury Soldier. O’Donovan was not the only sculptor to create both Union and Confederate memorials – Alexander Doyle did several important Robert E. Lee statues in New Orleans and the South and also did some Union memorials.

Matthew Brady

The War in Pictures

For 5,000 years, sculpture and paintings were the classic art forms depicting the brutal wars of human history. But the Civil War ushered in photography as a new medium to record the terrible reality and earnestness of war, wrote the New York Times.

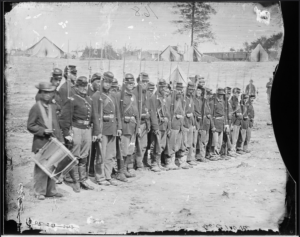

New Yorker Mathew Brady (1822-1896), a son of Irish immigrant parents, was the famed photographer who documented the Civil War, earning him the well-deserved title, Father of American Photojournalism. Already a successful photographer before the war, Brady received personal permission from Lincoln to shoot the war. He embedded 35 photo teams to follow Union troops for the entire war.

Brady’s and his assistants Timothy O’Sullivan and Scottish immigrant Alexander Gardner shot over 10,000 photos, including portraits of soldiers and camp life, engineering and transportation feats, and the battles themselves writes Webb Garrison in his book, Brady’s Civil War.

The 375 photos in the Mathew Brady Collection at the Boston Public Library include “not just the gruesome carnage but pictures that tell the broader story of the war,” says Susan Glover, Keeper of Special Collections at the library. Many of the photos are from the Massachusetts 20th Regiment and the 9th and 28 Irish Regiments. The library has an ongoing exhibit and lecture series to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the Civil War.

James E. Kelly

Sculptor of American History

James E. Kelly (1855-1933) was born in New York City and created over a dozen Civil War monuments. Among his notable works are Soldiers and Sailors Monuments in Troy and Yonkers, the Monmouth Battle Monument in New Jersey, and the General John Buford Memorial in Gettysburg.

Kelly was a popular illustrator for magazines and interviewed dozens of political and military leaders while sketching them. His interviews with over 40 Civil War commanders, including Generals Grant, Meade, Hancock, and Sherman, were published in a book called Generals in Bronze by William B. Styple, who in 2006 raised funds to put a tombstone on Kelly’s unmarked grave at St. Raymond’s Cemetery in the Bronx.

In addition to the sculptors described above, dozens of other Irish-American sculptors contributed to the artistic narrative of the Civil War, including Stephen J. O’Kelly, Alexander Doyle, Andrew O’Connor, John S. Conway, Charles J. Mulligan, and many more.

As the 150th anniversary of the American Civil War unfolds over the next four years, the work of these artists serves as a reminder of how society turns to art to explore grief, conflict, and resolution, and how immigrants continue to play a lasting role in the American Experiment.

Michael Quinlin is the author of Irish Boston and editor of Tales from the Emerald Isle and Other Green Shores. He founded the Boston Irish Tourism Association and created Boston’s Irish Heritage Trail, a three-mile walking tour of Irish landmarks. Mike lives in Milton, MA with his wife Colette, and son Devin. He works full-time in the tourism industry.

Michael Quinlin is the author of Irish Boston and editor of Tales from the Emerald Isle and Other Green Shores. He founded the Boston Irish Tourism Association and created Boston’s Irish Heritage Trail, a three-mile walking tour of Irish landmarks. Mike lives in Milton, MA with his wife Colette, and son Devin. He works full-time in the tourism industry.

Your site is very interesting, many thanks. Have you come across a Civil War artist John Mulvan(e)y who was also an illustrator and photographer who worked for Matthew Brady? Any leads would be most gratefully accepted.

Many thanks, Niamh O’Sullivan

Brilliant piece. One admirers these works in parks and cemeteries in the U.S. but does not often think of the artists who created them. In a museum setting, one’s impulse is to consider the artist but this is not so with public pieces. I never thought of this before reading this article. The only artist I was aware of among the ones listed was Launt Thompson and yet, for some reason, never thought of the many other `Thompsons’ who must have sculpted the statuary I’ve admired across the U.S. Thanks for an excellent article. Much appreciated.

I’m a second year graduate student for the Master’s Degree in American History at the University of North Carolina, Greensboro. My field of specialization in the Civil War/Reconstruction period.

Thank you, thank you, thank you for this article. I’ve just posted it to my Facebook page.