At the dawn of American cinema, when most film companies were already heading west to Hollywood, one company traveled east – to Ireland. The little-known story of the Kalem Company, or “The O’Kalems,” as they were fondly called, is the subject of a new collection from the Irish Film Archive.

A steam engine chugs into a small railway station in Ireland and a handsome, well-dressed man steps onto the platform, looking around him. He confers with a train conductor for directions, and we soon see that he has hitched a ride in a one-horse cart, and is traveling along a country road with a contented expression of home on his face.

As familiar as it sounds, this is not the opening scene of John Ford’s iconic 1952 film The Quiet Man. It is a moment near the end of The Lad From Old Ireland, a silent film in flickering black and white, directed by Sidney Olcott and produced by The Kalem Company in 1910. It was the first transatlantic film, the first-ever fiction movie to be made in Ireland, and it was extraordinarily ahead of its time. Despite these landmark achievements, both the film and the Kalem Company have been largely forgotten.

The early 1910s saw American cinema set off on a course that would define it for the better part of the 20th century. Though the industry initially got going in New York, occupying buildings in Chelsea, shooting on rooftops and in the accessible wilderness of New Jersey, film pioneer D.W. Griffith’s first shoot in California in 1910 helped to spark the industry’s great migration west, to Hollywood. In the years that followed, most of the major production companies, including The Kalem Company, established studios in California.

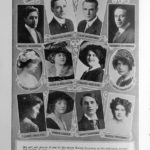

But a few of the Kalem stars were already creating their own, different path, traveling 3,000 miles in the opposite direction – to Ireland. Led by director and actor Sidney Olcott and scenarist and daring leading lady Gene Gauntier, the Kalems first traveled to Ireland in the summer of 1910, and would return almost every summer until 1915, making close to thirty Irish films. Though they also shot in a great variety of other countries, including England, Germany, Egypt and Palestine, their Irish work proved so popular that they were sometimes called “The O’Kalems.” (The company name, derived from the last names of its founders, George Kleine, Samuel Long and Frank Marion, had no official Irish connection.)

Their little-known journey is the subject of Blazing the Trail: The O’Kalems in Ireland, a new feature-length documentary written and directed by Peter Flynn, a scholar at Emerson College and founder of the Boston Irish Film Festival, and produced by Tony Tracy of NUI Galway. Blazing the Trail was recently released as part of The O’Kalem Collection, a two-disc set that contains all eight of the surviving Irish Kalem films, compiled by the Irish Film Institute’s Irish Film Archive.

Speaking with Irish America from Boston, Flynn, who grew up in Dublin, recalled how he first learned about the O’Kalems over the course of his studies in Irish film, and then encountered them again as an intern at the Irish Film Archive in the early ’90s. “They always stuck with me,” he said, “and then many years later I’m here teaching American film history and I see no mention of these guys, and I just keep wondering why, why are they forgotten? That curiosity led to researching, and the more I researched them, the more important and central I realized they were to American film.”

He believes that if the O’Kalems are left out of the picture, we run the risk of forgetting “how important Irish audiences in America were – both as an audience to be courted by early filmmakers, and as an audience that was demanding to be represented in cinema.” We also risk forgetting “the role that Ireland played as a location – as perhaps one of the first really, truly exotic locations to early American audiences.”

Making the documentary, he said, was much like detective work. He gathered all of the surviving evidence and material he could find on the Kalems in hopes of answering three major questions: Who were the Kalems? What made them go to Ireland? Why was their story so forgotten?

As Blazing the Trail tells in beautiful detail, the Kalems first went to Ireland in that summer of 1910 as the first stop on a larger overseas trip. Docking in Cobh, they worked mostly in Cork and a bit in Killarney, Co. Kerry, shooting The Lad from Old Ireland, which they would finish upon returning to New York. That first O’Kalem film, directed by and starring Sidney Olcott and written by and co-starring Gene Gauntier, tells the story of Terry O’Connor (Olcott), a young Irishman who leaves his love, Aileen (Gauntier), to try his luck in America. He works as a laborer in New York for a few years, before finding success in the local political scene. He seems to have mostly forgotten about Aileen, who, back in Ireland, faces eviction from her house following her grandmother’s death. The local priest writes to Terry, who immediately sails back to Ireland to save the day.

The movie was a critical success – and a popular one.

Aside from the “firsts” it holds claim to, what made The Lad from Old Ireland so unique was the way it presented its Irish characters. They weren’t the cartoonish drunkards seen in other films from the same era, but realistic, dignified people with a true-to-life story.

It was particularly well-received by the burgeoning middle-class Irish communities, who until then had not been portrayed in film. As Flynn explained, the O’Kalems were “the first filmmakers to acknowledge the realities of the Irish immigrant experience. You look at those films – particularly The Lad from Old Ireland or His Mother – and you see the pain and the suffering that led people to emigrate, and what they lost in going to America. You get a sense of how important Ireland remained to them.” And, he added, the incredible thing was that the Kalems were bringing “images of Ireland – moving images of Ireland – back to the Irish in America, and that was of almost sacred importance.”

Blazing the Trail speculates that this sensitivity may have come from Olcott, whose mother was born in Howth, Dublin, and had immigrated to Toronto, where Olcott was born. His attachment to Ireland would prove to be the strongest, and would see him make films of an increasingly political and nationalistic nature, returning to Ireland even after the Kalem Film Company was no more.

After their success with The Lad from Old Ireland, Olcott and Gauntier returned to Ireland in the summer of 1911, with more time and a bigger, better organized cast and crew. They set up base in a small Killarney town called Beaufort, staying in the Beaufort Bar & Inn, which remains there today and is still operated by the same family that welcomed and befriended the O’Kalems – the documentary includes an interview with its current owner.

Over the course of that summer, the O’Kalems made eighteen films, four of which have survived and are included in the DVD. They drew inspiration from classic Irish texts such as Dion Boucicault’s The Colleen Bawn and the Thomas Moore song “You Remember Ellen,” and from the landscape of the Killarney Lakes that surrounded them. Another film from that summer, Rory O’Moore, was based on the Irish rebellions of 1798 and 1803, and featured Beaufort locals dressed up as both Irish rebels and British soldiers, giving them a rare chance to, as Flynn phrased it, “act out their own history.”

Their last trip to Ireland as the O’Kalems took place in the summer of 1912. That autumn, Olcott parted ways with the Kalem Film Company, and Gauntier went with him. Together they formed the Gene Gauntier Feature Players, and spent a last summer working together in Ireland. By 1914, Gauntier and Olcott’s working relationship had deteriorated. Olcott made his final Irish films in Beaufort in the summer of 1914. His last one, Bold Emmett, Ireland’s Martyr, was based on nationalist rebel Robert Emmet (one “t”) and pointed to Olcott’s own nationalistic sympathies, as well as the rising tensions in Ireland in the years leading up to the 1916 Rising. It enjoyed a short release in Ireland before being banned by the British government.

Olcott, who married Valentine Grant, an actress from the Kalem Company, went on to have some success working with Paramount as a writer. Gauntier married and then divorced Jack Clarke, another Kalem leading actor, and spent the rest of her days in Barbados and with her sister in Sweden, unable to find acting work. In 1928, she published her autobiography, Blazing the Trail, from which the documentary draws its name. By the time The Jazz Singer, the first talking picture, came out in 1927, no one was making films like the O’Kalems. They had occupied a strange space – light-years ahead in terms of their on-location shooting and subject matter, but also practitioners of a dying art.

An astonishing 90% of all films made during the silent era have not survived. As Kasandra O’Connell, the director of the Irish Film Archive, recounted, tracking down the Kalem films has been no easy task. As silent films, they were easily distributed in other countries since the inter-titles between the scenes were easily translatable. As a result, “we come across Irish films in international archives rather frequently, but – especially with silent films – they can be hard to identify since you really have to know what you’re looking for.” Case in point, the only surviving copy of The Lad from Old Ireland had German inter-titles, which the IFA translated for the DVD. Both For Ireland’s Sake and His Mother were found in the Netherlands, in the Dutch Filmmuseum. Come Back to Old Erin was only found in 2010, at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Both O’Connell and Flynn hope that the collection might result in other Kalem films being located and repatriated. “What’s really interesting for us now,” Flynn said, “is that chances are there is more to be discovered out there. Hopefully we might come across another film or another article or interview, something hidden that will help to answer these questions. So, in a sense, although the film is done and completed, the process of trying to figure out who the Kalems were – that goes on.”

Obscure as they became, one has to wonder about their legacy. Could there be, for example, a direct connection between The Lad from Old Ireland and The Quiet Man? Or are the similarities just a product of emigration and return being so central to the Irish story? Subliminal or not, Flynn sees a definite impact. “They’ve had a tremendous influence, one that’s never really been acknowledged,” he said. “But if you look at the way in which the Irish landscape is framed by Sidney Olcott in those films, and then you compare it to the way in which John Ford represents Ireland, there’s a very strong connection. Now, I don’t know if John Ford ever saw those films,” he added. “But in terms of style and the way of representing and visualizing Ireland, there’s a connection there. I don’t think we can really understand what Irish cinema and Irish-American cinema is without going back to the roots, and those roots are to be found in the Kalem films.”

Click HERE to purchase The O’Kalem Collection (1910-1915).

See more O’Kalem images from the Irish Film Archive:

Saoirse Ronan takes viewers through the Irish Film Archive’s highlights:

Wonderful article! Gene Gauntier was true movie pioneer and deserves more recognition.

My great-grandfather, J.P. (Jack) McGowan, appeared in “The Lad from Old Ireland” (1910) for which Gene Gauntier wrote the screenplay. When the O’Kalems returned to Ireland in 1911 for more filming, Jack had feature roles in “His Mother” and “The Colleen Bawn.” His skill as a horseman was displayed in “The Special Messenger.”

In late 1911/early 1912, Jack, Gene, and other Kalem employees began a long journey ending in Egypt, where they made the five-reel movie “From the Manger to the Cross.” This was the first feature-length film ever made. The troupe became known as the “El Kalems.”

(A delightful description can be found in John McGowan’s “Hollywood’s First Australian, the Adventurous life of J. P. McGowan.”) Jack was with the troupe for the 1912 trip to Ireland for more filming. He stayed with Kalem after Gene left, becoming a director with a focus on railroad movies.

That led him to creating “The Hazards of Helen,” featuring Helen Holmes, my great-grandmother. (I’ve written a short biography of her at http://www.necessarystorms.com)