No Christma-a-as! No Christma-a-as!” Such was the town crier’s chant in the streets of 17th-century Dublin when Ireland felt the hammer blow of Oliver Cromwell’s Puritan iron fist. Garlands of greenery were pulled down and publicly burned. Revelry was forbidden. Priests were imprisoned. But the Irish people found ways to celebrate their most loved holiday despite the hazard.

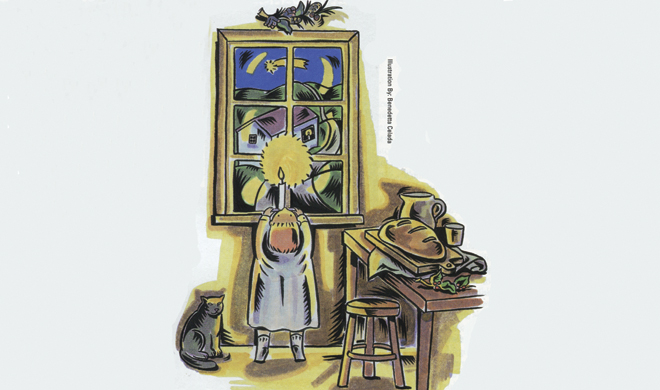

Those troubled times were in fact the origin of the custom of putting a lighted candle in the window on Christmas Eve. The honor of lighting the candle was given to the youngest daughter of the household, even better if she were named Mary. According to one belief, the candle served as a symbol of welcome to Mary and Joseph who desperately sought shelter on the first Christmas night in Bethlehem. It also served as a signal to any priest seeking refuge and protection that he was welcome to say Mass free from danger in that household, albeit in secret. In our own time, the one candle has multiplied to hundreds of colorful electric lights that glitter on the eaves, roofs, and windowsills of homes all through the Christmas season.

Another Christmas Eve tradition based on Mary and Joseph’s fruitless search for shelter was common practice in many Irish homes for more than a millennium. After dishes from the evening meal were cleared, the household’s front door was unlatched and the kitchen table was set with a large pitcher of milk, a loaf of bread filled with raisins and caraway seeds, and a lighted candle. This offering of hospitality to the Holy Family, or any other hapless wayfarer who might be caught traveling on the Night of Nights, provided the origin for another of our modern traditions: the plate of cookies and glass of milk children leave out for Santa Claus.

Baking, always a prime activity in Irish kitchens, reaches its zenith at Christmas and begins in late October with the making of the season’s fruitcakes. Evidence that the time for holiday baking has arrived is apparent when grocery shelves filled with plump sultana raisins and minced candied fruit peels. Redolent with spices and regularly doused with liberal splashes of whiskey, the fruitcakes are left to age until a week before the holidays. Then they are covered with a thin sheet of almond marzipan and iced with snow-white royal frosting. Some creative bakers go a step further and decorate their masterpieces with holly and berry designs cut from bits of candied citron and cherries.

In times past, three fruitcakes were usually prepared. The first cake, cut at midnight on Christmas Eve and passed around with accompanying glasses of whiskey and cups of tea, marked the beginning of the Season’s Twelve Joyous Days. The second cake made its appearance at midnight on New Year’s Eve when it was distributed with similar liquid refreshments and wishes for a prosperous new twelve-month cycle. The third cake was saved for Women’s Christmas. Better known as The Feast of the Epiphany, the day was so named because it marks the Twelfth Day after Christ’s birth when Mary first appeared in public and took her Son to the temple so that He might be seen and blessed by the Elders.

But there was more to Irish Christmas baking than fruitcakes. Kitchens also bloomed with the scent of two other delights: Seed Cakes and Mincemeat Pies. Seed cakes were filled with caraway seeds, a common medieval spice. Mincemeat, which also made its first appearance during the Middle Ages, originally included chopped meat and suet, but today is a mixture of chopped apples and nuts, candied citrus peels, raisins, spices, lemon juice, wine, and brandy. The spices, once thought to represent the gifts of the Magi, were in fact necessary preserving agents along with the brandy and wine.

As with all other Holy Eves, the day before Christmas was an ordained Fast Day and people were forbidden to eat meat. Until this century, going without meat was commonplace for Ireland’s poor, a description that fits most of the population. In the 16th century, Sir Walter Raleigh introduced potato farming on his estate in County Cork, and onions, potatoes, and milk products became mainstays of the workingman’s diet.

Christmas and its Eve were much-anticipated exceptions. For the Night Before Christmas, families usually managed to acquire a bit of fish that was stewed with everyday vegetables in a thick cream sauce. After dinner, small circular Seed Cakes were passed around to each family member, and woe to anyone whose cake crumbled prior to being tasted, for such an ill omen augured bad luck for the coming year. What with Seed Cakes and the season’s first fruitcake playing such important roles on this momentous eve, people often referred to it as The Night of Cakes.

As for Mincemeat Pies, Oliver Cromwell and his minions enforced strict edicts that forbade making the pies for several reasons. In Ireland, as elsewhere in Europe, the pies were baked in an oval crust meant to represent the infant Christ’s cradle. Cromwell’s cohorts considered the form a heretical use of a sacred image. The ban also extended to the pie’s rich ingredients and liquors, sinful indulgences that Puritan dogmas rigidly prohibited. After Restoration, the pastries were made legal again, but during the forbidden years, stalwart Irish women risked imprisonment by continuing to make mincemeat pies for secret Christmas celebrations.

Except for the oppressive Cromwell years, church bells have always rung throughout Ireland on Christmas Eve. For centuries the bells began tolling at eleven o’clock and ended with the twelve strokes of midnight. Known as ‘the devil’s funeral knell,’ the practice grew out of the folk belief that the devil died when Christ was born, and people believed that the sound of the bells would keep evil away from their parish for the next twelve months. Today, bells still ring, but only to call the faithful to Midnight Mass and announce the start of the joyous holiday season.

The weeks leading up to Christmas Eve have always been filled with traditional holiday preparations. In rural areas, people flocked to nearby towns to “bring home Christmas” from the year’s biggest market gathering. Called Margadh Mor, or Big Market, it was an occasion to exchange the products from their farms – butter, eggs, hens, geese, turkeys and vegetables – for luxuries like dried fruits, spice, sugar and tea. Though tea is now Ireland’s favorite beverage, it was once a rare commodity and was often only served on Christmas Day. Whiskey, wine, and beer were also purchased, as were trinkets and sweets for the children.

In An Irish Country Christmas (St. Martin’s Press), author Alice Taylor recounts her holiday memories of growing up on a farm in County Cork. Plucking the Christmas geese and peeking through slats of the barn where they hung frozen stiff until they were brought in and stuffed for Christmas roasting. Trooping into the forest armed with a rusty saw and bits of twine to gather holly and ivy with her brothers and sisters. The meatless Christmas Eve dinner, eaten while a savory ham boiled in a bastable pot on the turf fire. Hauling in Blockeen na Nollag, the Christmas Log, and watching it crackle on the hearth. Lighting the Christmas candle, “the key that opened the door into the holy night.”

My childhood memories growing up in Philadelphia are somewhat different but equally unforgettable. Weeks of cookie baking. Placing electric candles in each and every window. Hanging greenery, mistletoe, and the cards we’d received from friends far and near. Setting up the precious Lionel trains my mother gave my father on their first Christmas. Trudging through the snow to bring back a prize tree. Placing every ornament with precise care. Fish for Christmas Eve dinner. Milk and cookies for Santa. Roast turkey and mincemeat pie on Christmas Day.

And when my daughter was a child, we created a host of special traditions of our very own. As you most surely have done for yours. May the joy of the season linger in your hearts all year long.

Sláinte!

RECIPES:

Seedcake

(The Art of Irish Cooking – Monica Sheridan)

1 cup soft butter

1 cup sugar

4 eggs

11⁄2 teaspoons caraway seeds

2 tablespoons Irish whiskey

21⁄2 cups sifted cake flour

1⁄2 teaspoon baking powder

Line an 8-inch square cake pan with waxed paper. Preheat oven to 350 degrees. In a large bowl, cream the butter and sugar together until light and fluffy. Add the eggs, one at a time and beat well. Stir in the whiskey and caraway seeds. In another bowl, sift the flour and baking powder. Gently fold the flour mixture into the egg mixture. Pour the batter into the cake pan. Scatter extra caraway seeds on top. Bake for one hour, or until a cake tester can be withdrawn clean. Remove the seedcake from the oven and let sit for ten minutes. Extract the cake and place it on a wire rack to finish cooling. Remove paper and cut into squares before serving. Makes 8 servings.

Seafood with Cheese Sauce

(In An Irish Country Kitchen – Clare Connery)

1 pound cod fillets, cut into finger-size strips (salmon can be substituted)

1⁄4 pound mushrooms, sliced and minced

1⁄4 pound cooked bay shrimp

2 cups milk

1⁄4 medium onion

6 black peppercorns

1 blade of mace

(or 1⁄4 teaspoon freshly grated nutmeg)

1 bay leaf

2 tablespoons butter

2 tablespoons flour

salt and pepper

1 tablespoon fresh lemon juice

1⁄4 pound grated cheddar cheese

Preheat oven to 350 degrees. Butter a baking dish large enough to hold the fish. Pour the milk into a saucepan. Add the onion, peppercorns, mace, and bay leaf. Bring to a boil, then remove from the heat and steep for 15 minutes. Place the fish in the baking dish, and scatter the mushrooms and shrimp on top. In another saucepan, melt the butter and stir in the flour to make a paste. Cook for a few minutes, stirring all the time. Strain the hot milk into the saucepan, stirring constantly to prevent lumps. Season with salt and pepper, and cook over low heat to thicken. Add 2/3 of the cheddar cheese. Stir until the cheese is completely melted. Add lemon juice. Pour the cheese sauce over the fish and sprinkle with the remaining cheese. Bake for approximately 20 minutes until golden. Serves 4. (Note: Recipe can be doubled without problem to serve more.)

[…] of Halloween was one of our most-read articles of the year . In the current issue she writes about Irish Christmas traditions. Tom Deignan, our Irish Eye on Hollywood, keeps us up-to-date on the silver screen and also […]