Filmed carefully over a period of twelve years, the documentary Knuckle sheds light on the inner workings and on-going feuds of three Irish Traveller clans. Up next for the film: a New York premiere and an HBO spin-off series.

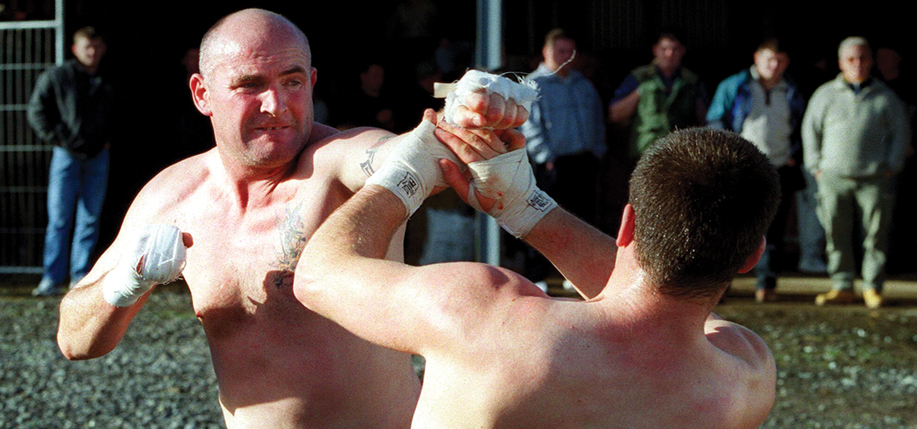

Don’t let the bandaged fist in the photo fool you. Knuckle, Ian Palmer’s documentary about the bare-fisted boxing tradition of the Irish Travellers, might be about blood, but it’s not about gore. The blood Palmer seems most interested in is the stuff that pumps through the veins of the intricately connected Traveller community he visited and filmed over 12 years, a society where cousins marry, work together and, when the occasion arises, beat each other senseless.

“I wanted to make a film from inside their world,” Palmer told indie/WIRE when Knuckle premiered earlier this year at the Sundance Film Festival. “The idea and the approach was simple. I spent as much time as I could with the families with a minimal crew and small camera.”

His approach resonated at HBO, which is adapting the documentary into a new drama series. Industry blogs hint that the HBO treatment will trend toward dark comedy, since it is being developed by writer Irvine Welsh (author of the gritty novel Trainspotting, on which the film of the same name was based), and director Jody Hill of Rough House Pictures, the project’s producer, whose politically incorrect comedy Easthouse & Down also airs on HBO.

Knuckle will have its New York premiere on September 30 at Irish Film New York, which will feature five other recent Irish releases. This new screening series of contemporary Irish films is co-presented by New York University’s Glucksman Ireland House, and runs September 30 through October 2 at NYU’s Cantor Film Center.

Festival founder and curator Niall McKay, who is also the founder and director of the San Francisco Irish Film Festival and co-founder of the LA Irish Film Festival, said he deliberately chose films for the series that depict Ireland as it is today.

“I particularly wanted films that had a real physical effect on me,” he said, “ones that made me cry or laugh or get angry.”

“We’re pleased that Niall McKay has chosen to work with Glucksman Ireland House to present this excellent addition to the city’s arts scene,” said Loretta Brennan Glucksman, Chair of the Glucksman Ireland House NYU Advisory Board. She praised the festival for presenting “works that would not otherwise be seen by a wide audience. It should be an exciting experience for our Irish American community.”

Besides Knuckle, Irish Film New York will also feature the New York premieres of the Galway Film Fleadh-winning Parked with Colm Meany, a study of a friendship between two men who live in their cars, and The Runway, the story of a downed pilot in Cork rescued by a little boy, with Weeds star Demián Bichir. Other films include the bittersweet coming-of-ager, 32A, directed by Marion Quinn, a hilarious peek at Dublin teenagers called Pyjama Girls, and Sensation, about a man who tries to lose his virginity but ends up running a brothel. Directors and stars of the films will appear at Q&A sessions after each screening.

There will also be an industry panel in conjunction with NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts, where filmmakers and producers will discuss the direction of Irish film at home and abroad.

McKay says the mission of Irish Film New York is to expose American audiences to the best in Irish contemporary cinema and to give Irish filmmakers “a fair crack at the U.S. market.” It will join with the San Francisco and Los Angeles Irish Film Festivals to bring the filmmakers of Knuckle, Parked, and The Runway on a tri-city tour in anticipation of each film’s U.S. release. Knuckle will appear in independent U.S. theatres this December, with The Runway and Parked following shortly after.

Director Palmer admitted to Irish Independent Weekend that he did not approach the filming of Knuckle like an investigative journalist.

“It was more about observing the [Traveller] families and trying to let the life reveal itself. The reasons behind the fighting were difficult to get at. The feuds stretched back over generations. It was always about defending your name and family pride.”

The three rival families that he studied, the Quinn McDonaghs, the Nevins and the Joyces, are all related, often sharing the same grandparents. As one of the women remarks, “We’re all one in the end.” Even if a Nevin married a Quinn, or a Quinn has a mother who is a Joyce, the rationale for fighting rests on defending just one family’s name.

While Palmer is able to ferret out the powerful origin of one particular feud, the sources of the disputes don’t seem as important as the disputes themselves. “Would it not be possible for you guys to get together to talk about it and make up?” the director asks Michael Quinn McDonagh, on his way to a fight in England. “You’re crazy,” Michael laughs, dumfounded at Palmer’s naiveté.

The matches are called “fair fights” and are organized with unexpected formality: when a challenge is issued, it is promptly accepted, a date and location are set, and the fighters hit the gym to train weeks before the match. Fair fights take place in secret locations with few onlookers. There are referees from neutral families and lots of rules. And everybody obeys the rules. Anyone who doesn’t is disqualified, and his family takes the loss.

Technology and money play crucial roles in this tradition-bound ritual: Families exchange videotaped challenges and fight results are reported by cell phones. Bets are negotiated for astonishing amounts of cash; winner (and family) takes all.

The fighters accept Palmer’s presence with the nonchalance of a generation bred on reality TV. But despite his desire to let the story emerge from the people themselves, they never forget the camera is there. Dodging it, challenging it, playing with it, they turn the camera – with narrator Palmer – into another character in the film.

Palmer said it was only during editing that he realized that the narrative would work better if he allowed himself to be an obvious part of his film. “The film is more honest for accepting that Knuckle is my experience of this world,” he said, “and my relationship to the people in the film and how that affected me.”

His “shaky cam” character dances around the fair fight scenes with a perilous immediacy. At any moment, you expect a fist to fly into the lens. Because he interviews both families involved in a fight, Palmer never appears to be taking sides. Even though he follows one fighter’s story more closely than others, he is not making a fight movie. There is no Big Match to decide it all, no good guys or bad.

James Quinn McDonagh, the soft-spoken man whose winning battles form the core of the film, says over and over again he doesn’t want to fight, but is provoked into it by the other families, claiming he’d like “to be known for something more positive.”

James doesn’t like to train either. “I’d rather be socializing,” he quips. But when a challenge comes from the Joyces or the Nevins, he comes out with fists blaring. “It’s the best way to sort things out,” he explains. Even after he swears off fighting, he is seen anxiously prepping his brother by cell phone before a fight, exclaiming as he waits for the results, “Grandfathers in Heaven, send Michael the power!”

Why do the fights continue? Palmer sees “fair fighting as still mainly about family and individual honor and pride,” a deeply felt emotion expressed here in macho posturing: “We will fight because we are men, we’re Joyce men.”

Then there’s the fast cash from the betting. The suggestion of inconsistent employment implies that fighting is a needed source of income, and might also be a way to establish self-respect when the outside world offers too little.

But within a closed community, the flip side of self-respect can be a cult of personality. Joe Joyce, an older man who nevertheless continues to fight, boasts, “I’m still King of the Travellers!” One of James’ opponents, the dewy-faced youngster, Davy Nevins, says the fights are not about revenge.

“James thinks he’s better than us,” he explains calmly. “People think he’s a god. I don’t want to defeat the Quinns, I just want to defeat James.”

Some Nevins relatives suggest a possible link between being a Traveller and the need to keep fighting. When an old man muses, “There’s always been wars,” the younger Spike Nevin replies, “But we’re Travellers. At least wars are about something. Something right.”

Conspicuously absent from the film are Traveller women, who are reluctant to appear on camera. Yet, the only strong voices condemning the fighting come from a sofa full of older women gathered for an after-fight party. “I think it should end,” one woman states firmly. “All this fighting over names. It’s an awful life to have. It should be finished.”

“I don’t know what they’re fighting for,” James’ mother adds.

“When my sons grow up, they aren’t doing it,” a much younger woman declares with convincing resolution. But she quickly adds a caveat, “If I can help it.”

Leave a Reply