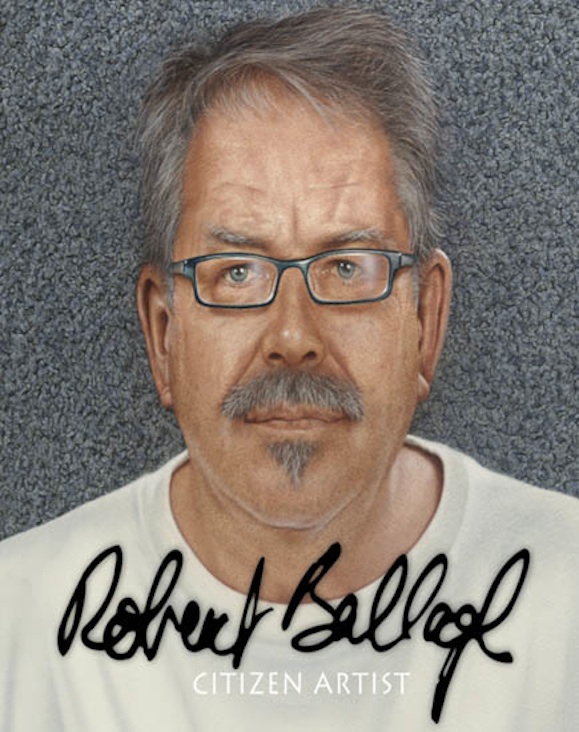

The extraordinary life and work of Robert Ballagh is celebrated in a new book, “Citizen Artist” by Ciaran Carty

I’ve often called Robert Ballagh the perfect Dubliner. He married the city, walked it, photographed it, painted it, and Dublin in turn – no mean city – has embraced him. He’s just done a portrait of James Joyce for U.C.D. If Joyce were around, he would have a lot of respect for another Dublin, Ballagh’s Dublin. For Bobby has populated the city. What do I mean by that? He has painted everybody – politicians, artists, poets, musicians (Dublin is a great music town), architects, sportsmen, scientists. To be painted by Ballagh is an event. He negotiates the marriages of two minds – sitter and artist – with revelatory tact. He has left a record of Dublin at a certain era that is and will be an extraordinary window into the life of this city. Ballagh’s Dublin.

Just down the road here is the Frick Collection. You can go in and see the Holbeins. Holbein tells you about every character in the court of Henry the Eighth. Anne Boleyn looks as if she just sat down yesterday. The great Ambassadors in the painting of that name are to me often more alive than the people looking at them. Holbein gives you eyes that see microscopically. Such intensity of perception makes the subject almost unreal. It’s as if an hallucination had been materialized.

Why do I mention Holbein? Because – I’m not fooling – Ballagh’s technical gifts are just as perfect. With that hyper-vision, the unceasing appetite for perfection, every feature, every smooth cheek, every furrow and the light in every eye is posed and re-made. Vision become visionary, his sitter held in an intense, intimate grip.

Robert is one of the few people of major visual arts gifts who didn’t leave. He showed it was possible to make a living as an artist in Dublin. His reputation has gone far beyond city limits. He’s known and respected all over Europe.

I respect Bobby for many things. Not just his art, his theater designs, his posters, book covers, his gifts as a designer. I marked him long ago, in 1970, when I saw his free translation of Delacroix’s Liberty on the Barricades. Liberty. There’s no greater social conscience in Dublin, in Irish art and letters, than Bobby Ballagh. I call him Citizen Ballagh. Because he is a full citizen. He is not a political artist, but an artist who is intensely political. He is an active figure in his society, he has a voice, and he uses it. It is a voice that is respected in the troubled North, now precariously pacified. He has been vocal when government cowardice is on display. Those government officials seeking the ease and comfort of forgetfulness have been called to remembrance by Mr. Ballagh. He has been a leader for civil rights in the North. And for artists’ rights. He is an ethical man, whose values are often a rebuke to those without them. His art and mine are very different. But we admire each other’s work. We offer each other that deepest of courtesies.

Is Bobby admired by other artists? It’s always surprised me that this extraordinary artificer does not receive the praise from colleagues that he should. In the power Dublin literary community, Bobby is held in the highest regard. Why not in segments of the artistic and critical establishment? I’ve thought about that. Is there a kind of genteel holdover from our colonial days in parts of the Irish visual arts establishment? Bobby seeks no favors. His art speaks as frankly as he does. His art is seen as Pop. It’s not. It’s a kind of hyper realism secreted brushstroke by brushstroke by his temperament and character.

Speaking of character. We know that the arts attract their quota of poseurs and esthetes. Bobby – and this was shared by his wonderful late wife, Betty – detests pretentiousness and artistic snobbery. His realism is a rebuke to all kinds of fakery social and otherwise. That doesn’t make you popular with the pretentious. He has lived a simple life as husband and father. If you want to know how a Dublin life – Ballagh’s life – was/is lived, look at the marvelous paintings of his domestic life.

He is a realist in life and art. And when he turns his own eye on himself, the results – in a great series of, in my view, historical self-portraits – are uncompromising to the point of brutality. He gave himself no quarter. The self-portraits remind me of Messerschmidt’s great sculptures on human expression in Vienna. They are a confessional autobiography in paint. You can see them in the extraordinary book that is our reason for being here – a story of art and the life of Ballagh – that tells you more about this extraordinary man and artist I am proud to call, friend.

I agree, wonderful and inspiring artist!