Joyce’s Legacy

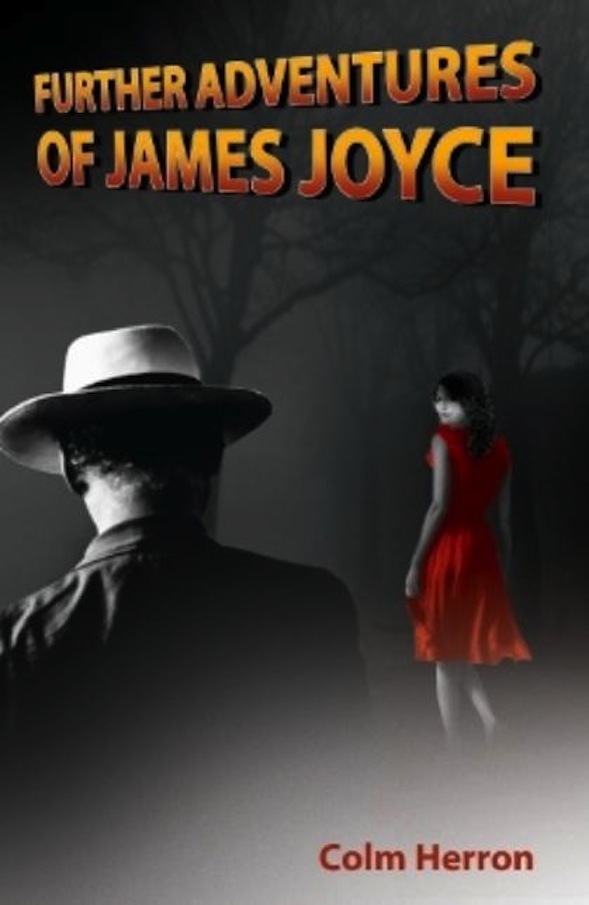

Colm Herron’s second novel, Further Adventures of James Joyce, is an extremely ambitious work. Herron, who lives in Derry, takes his readers back to the tense and volatile Derry of the late 1980s, where Myles Corrigan and Conn Doherty spend much of their time drinking and talking in a local haunt, The Drunken Dog. In the midst of the palpable grief, depression, violence, and political and religious unrest (which Herron powerfully yet subtly conveys) the book takes many meta-fictional turns. Myles often interrupts Herron’s narration as the author and his character bicker about narrative decisions. Three-quarters of the way through the book, James Joyce talks with Myles from beyond the grave and enlists his help in transcribing his last masterpiece. But in order for their plan to succeed, Myles must take over the writing of Further Adventures since Herron is suffering from incurable writer’s block and is contemplating killing off his protagonist in what Joyce and Myles deem to be all too neat an ending.

Though I thoroughly enjoyed his writing, I was left wishing Herron hadn’t “given up” and let his character – who is a much more pretentious and self-involved writer – take over. Still, Herron’s wit is clear throughout and I am excited to see what he writes next.

– Sheila Langan

(249 pages / Dakota / $10.42)

The ABCs of Joyce

For readers weary of the more tedious notes for and companions to James Joyce’s Ulysses, Julian Rios’ novel The House of Ulysses presents a new and exciting option. Rios, one of Spain’s foremost post-modernist writers, has approached Joyce’s work with insight, elegance and a very necessary sense of humor.

The book takes place in the fictional Ulysses Museum, where the visitors/readers are guided through eighteen rooms that correspond with the eighteen chapters of Ulysses. A cicerone (an old term for guide) is joined by Professor Ludwig Jones, a seasoned Joyce scholar, and three critics called A, B and C, each of whom have differing opinions concerning the text. In a clever reinterpretation of Joyce’s “man in the macintosh,” a mysterious man with a Mac computer lurks in the background and presents the traditional breakdown of each chapter’s title, setting, time, symbol, etc. As they enter each room, the members of the group first discuss and then re-tell the events and meanings of each chapter.

Though the book is not explicitly intended to serve as a guide to Ulysses, it seems unlikely that anyone unacquainted with Dublin on June 16, 1904 would have the patience to follow the meandering tour, which frequently draws from and sometimes parodies the various styles Joyce employed. But for anyone trying to work their way through or revisit Joyce’s work, The House of Ulysses is an engaging resource and a brilliant testament to the wonderful confusion and debate that Ulysses so frequently inspires.

– Sheila Langan

(280 pages / Dalkey Archive Press / $14.95)

The Room

Dublin-born playwright, literary historian and novelist Emma Donoghue has been critically lauded for her latest novel, Room, a finalist for the Man Booker Prize and an international bestseller. The attention she’s received for this unique, disturbing and awe-filled work is well deserved. Five-year-old Jack, who lives in the eleven-by-eleven-foot space that is the title’s namesake with his Ma, narrates Room with a voice that is as compelling as it is convincing. Room contains Jack’s entire world – the stain on the Rug where he was born, the Bed where he and Ma sleep, the Wardrobe where she shuts him in safely every night in preparation for the visits of Old Nick, and the TV that provides a confusing perspective of a world outside where the ten o’clock news is as much a fantasy as SpongeBob. As the story unfolds, it becomes clear that the space of Jack’s whole life and comfort is Ma’s prison, and her desperation to escape will require both of them to stretch the limits of their stifled imaginations. While a literal and thrilling story in its own right, Room also becomes a brilliant allegory for all parent-child relationships: for a small child, his mother can often feel like his entire world, while her child’s love both traps her and gives her very existence meaning. The inevitable opening up of the rest of the world is differently wondrous and traumatic for both of them. The space of Room emphasizes the closed-circuit intimacy of the mother-child connection, as well as the claustrophobia and incredible creativity and love therein. Look for an interview with Emma Donoghue in an upcoming issue of Irish America.

– Kara Rota

(336 pages / Little, Brown andCompany / $24.99)

The Sleepwalker

John Toomey’s debut novel, Sleepwalker, is a fable of spiritual decay and its emotional toll, a send-up of those coming into adulthood at a particular generational and socioeconomic point that offered them the life of their dreams, and their crushing disappointment when they come face-to-face with the lack of imagination that keeps them from doing so.

Sleepwalker is told by a bland yet unforgivingly observant narrator, documenting the downward spiral of antihero Stuart Byrne. Paralyzed with apathy, Stuart handles his successful if mind-numbing career and a series of events in his love life – ranging from an unexpected pregnancy to confronting his “platonic” relationship with his best friend, Rachel – with exponential ineptitude and helplessness. It is a feat of Toomey’s spot-on black humor and emotional generosity that the superficial and selfish Stuart is neither despicable or pitiable, but deeply familiar.

– Kara Rota

(272 p. / Dalkey Archive Press / 10.99 euros)

Going Blind

Mara Faulkner’s Going Blind is a memoir with many layers. Faulkner (no relation to William) uses her writing as a testing ground for figuring out her experience of her father’s blindness due to retinitis pigmentosa. This genetic form of gradual blindness, which her paternal great-grandparents took with them when they emigrated from Ireland, becomes an interesting vantage point from which Faulkner approaches other kinds of blindness, both physical and mental. Each chapter revolves around a different manifestation of being unable to see, from “blind spot[s]” to “blinders” to “turning a blind eye.” Under these over-arching topics, Faulkner covers a surprisingly wide range of issues, including moments in her personal history and historical events in which blindness (sometimes unintentional, sometimes willful) played a role. She moves seamlessly from the difficulties and prejudices faced by the blind, to the blind eyes that refused to acknowledge the Great Hunger, to the tragic saga of Native American displacement in the Midwest, to connotations of blindness in scripture and society.

Faulkner has clearly done extensive research and she expertly unfolds her findings and her confusions. She doesn’t just tell readers about her experience, but invites them to share in making sense of her contemplations and discoveries. While this is not a light read, it is an extremely rewarding one.

– Sheila Langan

(227 pages / Excelsior Editions / $19.95)

The Obama Family

In his book Pioneers: The Frontier Family of Barack Obama, Stephen MacDonogh writes a hypnotic account which pulls readers directly into the tales of wigmakers and pioneers, creating a historical arc of personal and national struggle and the triumph that leads to President Barack Obama.

The early chapters read like a novel, chronicling the journey of a post-Famine immigrant family, the Kearneys. Sections of Irish history are kept somewhat skeletal, giving the general outline of the conditions of Ireland in the discussed periods, mainly the Famine and immediate post-Famine decades. The focus is sharply kept on the Kearneys and later the Dunhams when marriage in the States begins the cross-cultural journey that would lead to the first African-American president of the United States.

More personal and character details are presented as the book moves to more recent times, painting an engaging picture of Stanley Ann Dunham, Barack Obama’s mother, who succumbed to cancer in 1995.

MacDonogh’s book is a fascinating trip into the genealogical past of a president. He gives life to people centuries gone, making it easy to forget, as one reads, that this is a story leading up to a political milestone. The pictures throughout the book are the perfect visual component for readers to latch onto as the generations proceed from Offaly to Ohio, from Hawaii to Washington.

– Tara Dougherty

(288 pages / Brandon Books / $34.95)

In Search of Craic

“Just what the world needs: another bloody book about Ireland.” Maybe not the best way to start off a book about Irish music, but Colin Irwin seems to make it work. In his book In Search of the Craic: One Man’s Pub Crawl Through Irish Music, well-respected British music journalist Irwin sets out on a trip to discover Irish music in the present day and through his travels finds etchings of the past in all modern playing. Iriwin makes the point that other than the few exceptions of The Chieftains and Clancy Brothers, traditional Irish music remains absent from the charts. The true soul of Irish music is to be found in seisiún, and Irwin takes it upon himself to embark on a thirsty, rambunctious pub crawl.

Touching on the legacy of Irish music giants like Seán Ó’Riada, who built classical Western music sounds around traditional Irish songs, all the way to the worldwide sensations of U2 and Enya, Irwin also gives a solid history of the more modern musical journey of Ireland. His troubles finding certain artists or pinpointing origins of certain traditions bring the reader into the trip with his tension-and-release style of storytelling. It is an impossible feat to understand the evolution of Irish style or the X-factor that makes it so captivating, but as Irwin recognizes, the magic is often in the mystery.

– Tara Dougherty

(320 pages / Carlton Publishing Group / $15.95)

Leave a Reply