Many of the 1.8 million Irish who emigrated to Canada and the U.S. between 1845 and 1855 found employment in the dangerous but lucrative mines that played a vital role in building American industry. A documentary, Butte, America, shows how over the following decades, the American Industrial Revolution swallowed entire families who lived in mining communities, as the often deadly work caught immigrants between the power of the wealthy companies and the pull of unions.

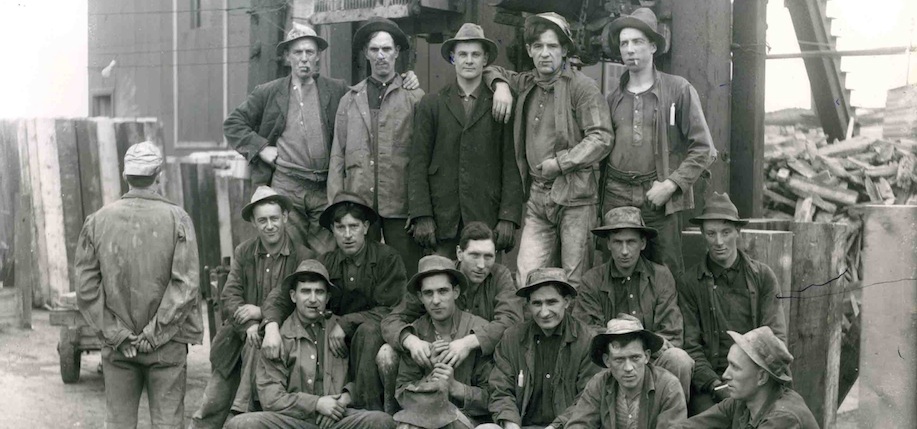

Narrated by Gabriel Byrne, Butte, America is a documentary that tells the story of the most profitable hard rock mining town in American history. Through historical narrative and interviews with mine survivors and their families, the film captures the pioneering spirit that drew men to work in the mines, the emotional ties that formed in mining communities, and the powerful hold that the mining companies had over every aspect of their lives.

“I never said goodbye in the morning, going to work. I’d say see ya, so long. Never goodbye,” says John T. Shea, an Irish ironworker, in the opening moments of Butte, America. This cheerful spirit belies the underlying knowledge all the miners must have had that their work could mean an early death for them. Butte’s mines were statistically the most dangerous in the world, and required immense manpower to operate. In the early 1870s, Butte was a mining town on the verge of becoming a city full of immigrants in search of employment and the American Dream. When the advent of electricity demanded more copper, the “Copper Kings,” industrialists Clark, Daly and Heinze, called for more manpower, pushing Butte’s population near 90,000. Immigrants flowed in from Ireland, England, Lebanon, Canada, Finland Austria, Italy, China, Montenegro, Mexico, and more: the “no smoking” signs in mines were written in sixteen languages.

The Irish, however, felt a special connection to Butte. Beginning their immigration during Famine times, many came from the Beara Peninsula where they had mined before leaving for America. They arrived in Butte by way of Nevada’s Comstock Lode, Pennsylvania’s coalfields, and Michigan’s copper mines. They arrived from Cork, Mayo, and Donegal. According to David Emmons’s book The Butte Irish, 12,000 of Irish descent were living in Butte by 1900, where the population was then 47,635. At a quarter of the population, Irish made up a higher percentage in Butte than they did in any other American city at the turn of the last century. Seventy-seven various families of Sullivans left Castletownbere, Cork and came to Butte. By 1908 Butte hosted 1,200 Sullivans.

The land in Butte was owned by the mining companies, and mining families paid ground rent to live there. As the companies fought for control of the fruitful mines, the larger companies expanded into railroads, logging and other industries, pushing their smaller competitors out of business. Monopolies meant that corporations held greater and greater power over the families that lived in mining towns, and unions could do little to change the occupation’s hazards. Butte was awash with widows raising large families alone, left with no insurance or income. The women held several jobs, and children contributed to the workforce as soon as they were able, ushering in the age of newsboys. Some 16,000 miners worked in the connected honeycomb of mines that lay underneath Butte, all with beautiful names that belied what went on underground: Anselma, Alice, Lexington, Bell Diamond, Mountain View, Moonlight, Silverbowl, and on and on.

In 1899, Copper King Marcus Daly joined with William Rockefeller, Henry Rogers and Thomas Lawson to form the Amalgamated Copper Mining Company, which soon changed its name to Anaconda Copper Mining Company. Marcus Daly was born in 1841 and raised near Ballyjamesduff in Co. Cavan. In Butte, he found a rich and plentiful source of precious metals, and became one of the wealthiest men in the West when demand for copper rose.

Daly was known for his tendency to hire Irish whenever possible. He is credited with paying good wages and was more benevolent than many other mine owners of the era. Unions were allowed to operate in his mines while he was in charge, and there were no major labor disturbances during his leadership. He died on November 12, 1900 at the age of 58 in New York City from complications of heart disease and diabetes.

Known simply as “The Company,” by 1914 Anaconda Company had become the fourth largest corporation in the country and had full control of Butte. They controlled town and state legislatures, and miners were pushed to increase production. Under the stress, the miners’ union splintered into smaller factions, none of which were acknowledged by Anaconda. After 1905, Butte was a hub of organization for the “Wobblies,” or Industrial Workers of the World. As WWI hit, more and more copper was needed, and Irish miners were expected to work longer hours.

The conditions became, unthinkably, even more dangerous, culminating in a fire that exploded in the Granite Mountain Mine on June 8, 1917. Hundreds of miners were trapped inside; 168 bodies were found. The shocked town mourned. Miners demanded safer working conditions, but the mine owners refused. Butte became a violent place, with union halls blown up and miners jailed or even murdered. When a strike at one mine was sustained for seven months, the miners were accused of treason during wartime and marched into the mines at gunpoint when federal troops were called in. In the Anaconda Road Massacre of 1920, Pinkerton Agency guards hired by The Company shot a group of picketing strikers, killing one and injuring 16.

By 1920, industrial unionism was a thing of the past as the “Roaring 20s” ushered in an era of rampant capitalism.

Then 1929 hit America with the biggest bust it had ever seen. A new era for workers arrived in 1932 when FDR ran on his promise of a New Deal and support for labor unions. Newly confident union workers were legally empowered to strike, and many did so in a pattern of every three years: the length of a contract. This led to a striking cycle in which mining families were forced to do without, but mining communities supported them with a created economy of credit, gift and barter. This community support during strike times, which many considered the highest moral achievement, also helped the miners achieve a living wage.

Still, The Company’s hold on Butte was ever-present, as it became more and more entwined in the daily lives of the families who lived there. Company-sponsored picnics, parade floats, and children’s sports teams were common, and miners’ kids grew up playing in the toxic playgrounds near active mines. However, by the 1940s, Anaconda’s profit was largely supplemented by overseas mining in Chile, which gave The Company a significant advantage in negotiating mining contracts with unions.

After a lifetime in the mines, if they survived the day-to-day perils of the machinery and conditions, many miners experienced a buildup of silica dust in their lungs and died painful deaths. After WWII, the prominence of industrial manufacture meant that greater and greater quantities of metal were needed. In the 1950s, Anaconda shifted their operations towards open pit mining, which utilized equipment and machines over manpower and caused greater environmental degradation. Miners were consistently laid off, and those that remained were turned into drivers and machine operators, stripping the work of the pride that men had had in it for generations. Entire neighborhoods were bulldozed to make room for pit mines, and the remaining families were surrounded with gaping holes in the town they called home. When a fire swept across Butte, many believed it was set by The Company to destroy buildings in the way of more open pits. “They owned it, that’s all that mattered,” remembered one Butte citizen. “You can do anything you want when you own it.”

In 1977, Anaconda was purchased by the ARCO company, which started shutting down mines due to lower metal prices. Layoffs continued to wrack Butte economically and emotionally, as men who had given their lives to the mines were rewarded by being cast aside. In 1982, the pit mines began to close and unemployment was rampant. By 1984 the Berkeley Pit was the greatest poisonous lake in North America: thirty-three billion gallons of water laced with a toxic sludge of minerals and chemicals killed snow geese that migrated overhead and came into contact with the water. The environmental, emotional and economic devastation that characterized the rise and fall of Butte, Montana under the hand of the mining business remains evident today.

However, the spirit of community support that characterized Butte through the mining era remains. Since 1882, Butte’s annual St. Patrick’s Day festivities have provided an annual celebration of the city’s Irish heritage. Over 30,000 attend the parade held by the Ancient Order of Hibernians in Butte’s historic Uptown District. The annual An Ri Ra, held on the second weekend in August, is a cultural festival that focuses on the music, dance and language of Ireland. Thousands attend the event. Once called “The Richest Hill on Earth” for its natural resources, which along with hardworking immigrant labor was plundered for profit, Butte is carving out a new identity as a city with a rich cultural history and pride in its Irish heritage.

To purchase Butte, America: http://butteamericafilm.org/contact/purchase-home-dvd/

I want to work in the mine

Butte was the Copper kings fund the mother load

greetings from the other town the Irish built!!!

heres a review of ‘Shamrock City’ you’ll hopefully find of interest.

http://londoncelticpunks.wordpress.com/2013/10/07/album-review-solas-shamrock-city-2013/

Butte America was an interesting documentary. I give the Irish credit, they weren’t miners back home so had to learn on the job unlike their local rivals the Cornish who already had several thousand years of hard rock mining experience. Centerville was half Irish and half Cornish, the town had two of everything to cater to the two groups.

A lot of the Irish in Butte were actually ex miners from West Cork in Allihies where the Cornish Family the Puxleys operated a mine employing 1600 people from 1812 on. As the mine was down graded and during the famine many miners moved to Butte.

Also many Irish miners came from the Copper Coast of Waterford, Kingscourt Cavan (Marcus Dalys area), Avoca ,Wicklow. Many seemed to have come from Newcastle Co Down from fishing and farming backgrounds, the reason I cant tell.

My Great Grandad died in the fire in 1917.

Dad calls his dog Butte in memory of it.

My great grand uncle took part in the rescue there. He was on another shift that night but drafted in for his knowledge of the shafts and exits below ground.

My Great Grandfather Peet Kelly also died in the mine “accident” as my grandmother Catherine used to call it. My Grate Grandmother moved to Sacramento, with her two younger childern (Billy and Theresa) and left my gradmother with some nuns (seh was only 12 years oldat the time of her fathers death). My grandmother had to help with all the other children that were then fatherless and to care them after school (cooking, cleaning etc. to earn her keep with the nuns). My grandmother, at 14 years old, moved to Sacramento California to join her mother Rose Kelly and her younger silblings. I would like to come to Butte to do some more digging and do a little filming about the history of this side of the family… super interersted in seeing the documntary. I produce at local TV Show here in San Jose CA. Thanks for the read! Heathe Durham

thats great grandmother… typo

Did the cornish and irish get along well with each orher down in the mines?

Good question. Not one I have an answer for. I believe the Cornish preferred to work with fellow Cousin Jacks, but probably because they knew most were experienced hard rock miners. The Cornish also worked for tribute rather than pay. I don’t thing the Irish did, so I suspect the Cornish primarily used other Cornish miners to make up a team of tributers.

In the mines, yes. Above ground not so much. That’s as I recall it growing up in Butte in the 40s and

50’s. My Dad worked as a contract miner in his younger days and various above ground jobs as he aged. Never did get hurt mining. Lot’s of my relatives did (a couple died in the mines). The whole mining thing scared the crap out of me (went down once). Brave men all! I wound up a college professor…lots safer.

Butte is a model for Vermissa, in Conan Doyle’s The Valley of Fear.. Identifiable by the coal mining, iron works and the bare crown mountains. Fenian leader, John O’Connor Power, visited in 1875. In the novel, he is Birdie Edwards/John McMurdo/Jack Douglas. And Moriarty.

My uncle, Mick Mc Ginn, emigrated to Montana in the 1920s. His uncle, name unknown, was already working there and took Mick out to USA.

My great uncle Edmond Thomas emigrated from Cornwall and worked there after ww1 until the late 50’s. On my bucket list to go and see where he worked and lived. Interesting site you got here.

I had 10 Grand Uncle’s and 2 Grand Aunts – all from th same Murphy Family , Castletown Bere – emigrate to the Butte mines. One of the Aunties was the seamstress for the Puxley Family. One of my G Uncles invented a special mining hammer the helped improve productivity., I’m sure he did not get paid any extra foe it though.

My dad’s uncle Dan Kelly moved from Iowa with a law degree before 1910 and worked his way up, starting with Jefferson County Attorney, then Attorney General for Montana, then joined Anaconda and retired as a vice-president. I’m sure the political scene was a constant factor in his life, although I have yet to uncover anything more specific.

My grandfather James Woods worked in Butte and Alaconda mines from around 1908 returning to Ireland every few years to his family and returning to Butte after approx. 2-3 years for another spell there. This continued up to his last return to Butte which was in 1925. When he returned to Ireland and his family finally he spent the rest of his life on his small holding raising fat cattle for sale. I do have some photos of his time spent there.

Butte partly inspired Vermissa in Conan Doyle’s The Valley of Fear, 1914. Doyle spent several months in the US researching the Molly Maguires, who terrorised the communities of Pennsylvania. See ‘Moriarty Unmasked: Conan Doyle and an Anglo-Irish Quarrel’. pps. 49-57.

Professor Moriarty frames the novel, in prologue and epilogue.

Irish and Cornish miners would have been hard to understand they would have spoke in a pirate like accent.

I am of both descent my great great grand father was cornish and my great great grandmother was born in south australia with irish decent.

I’m looking for great-grandfather Daniel O’Shea. He was born in 1852 or 1853, and was from Castletownbere.. he and his family left for America via Cork. He became a miner in Butte, and when passed away of natural causes. There was a trunk of his that had his import paperwork, such as birth certificate. The family did not have the means to pay for shipment of his trunk to Seattle where the family settled. Our hope is that someone kept the trunk and perhaps we can retrieve his belongings.

I have found a few newspaper articles whilst researching my Cornish grandfather, James Penberthy Martin, who was a miner in Butte. He worked as a miner in the day, and then as a porter in the Klondyke Saloon in the evening. At the time he slept in a room at the back of the saloon. Two masked men broke in one night and entered his room (detectives suspected a hit). My grandfather grabbed his gun from uder his pillow and stood up but was shot several times, one bullet lodged in his forehead and the others hit him in the shoulder and back. He returned fire but missed the men who fled the scene. My grandfather went next door to the saloon of Mr. Odgers (another Cornish name) who called for the deputy sheriff.

A few years later the same saloon was attacked by a group of Irish miners.

It seems that this saloon was very pro-British and the Irish weren’t particularly fond of the place.

I have no idea about the men who shot my grandfather. I did ask him about the bullet wounds when he showed me the scars but he didn’t talk much. The detectives also said that he wasn’t cooperative.

Yeah, there were a lot of Irish, The Harringtons, for example, who ran an ice cream parlor in the Flats and a restaurant uptown. But there were Finns, too, even a neighborhood cn the east side called Finntown. And there were Magyars and Germans and Jews and Slavs. You name had to end in “ovich” to play quarterback in the 1950s on the gravel playing field. Butte was a cornucopia of different people, hard city, good people. I wish I could have reared my children there in days like those. Now Butte is a monument to what corporations can do to destroy a community.

I recently discovered I am related to the Mathew Penhale family. I was told son Russell Penhale was President of the Miner’s Union I’m guessing sometime in the 20’s. I would love to hear from you if you know anything about the family. My grandmother would have been Evelyn Penhale who died in 1920 before reaching her 19th birthday. I’m going to Butte 5/22 to seek on site information.

Robert Brodersen

I received my geology degree in 1964 from Tufts University. In 1966, I completed my stint as a junior officer, left the Navy and was offered a job as an ore sampler underground in Butte by Anaconda. I chose to start graduate school at the University of Michigan instead and eventually became a professor for the University of Missouri in Kansas City for fiur decades. Finally, we got to Butte in 2019. By then, the copper mines were largely closed and Butte had seen better days even though the School of Mines still existed and you could purchase a pasty. At that time the Anaconda was defunct and had lost its extensive properties in the Butte area. The town was dismal but the Irish heritage, that I personally share, was still evident.

I often wonder what would have happened to me and my family if I had taken the job sampling copper ores in the greatest hill on earth for Anaconda. Although I have no regrets about my life in Kansas City, working undergound for Anaconda for a couple of years, would have been quite an experience for a young man (provided that my life and health were spared).

You must have Cork ancestry judging by your surname?

Yes. Cork is where my Coveney relatives came from. They settled in the Boston area when they came to America.

My life to now at age 80 yrs

rmc

18 Nov 2022

My great great gran uncle paddy Mcguinness or Patrick who ran a pub in butte montana, its not there anymore but the house in lived in with miss neven is still there,he died around 1914 in roschester Minnesota but can’t find anything about him or his grave his land lady died the year before he did.

My great grandad George Tuckett work there as a miner also a mining sheriff he sent his two daughters home in ww1 to be nurses originally from Devon but left on a ship from Liverpool after working in skinnigrove near Middlesbrough