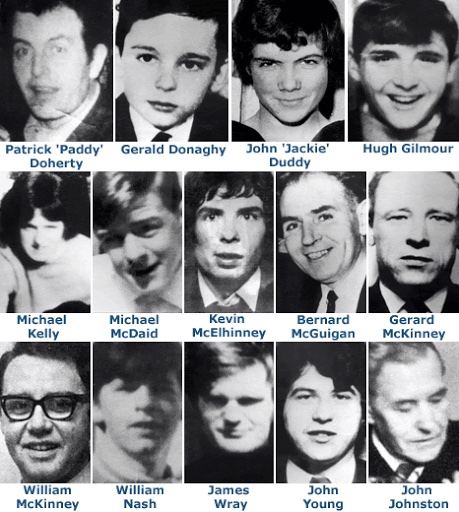

On January 30, 1972 members of the British Army fired upon unarmed civil rights marchers in Derry, killing 14 people, 13 outright, and one who would die later from his wounds. The marchers, about 15,000 strong, had been protesting internment without trial, which was introduced in Northern Ireland in August 1971, and involved mass British army arrests of more than 340 people from Catholic and nationalist backgrounds. Bloody Sunday, would come to be seen as a key event in the history of the Troubles, in that it escalated the conflict. It would take until April 10, 1998, and thousands of lives, before the Good Friday Agreement, brokered with the help of American George Mitchell, helped to bring an end to the conflict.

THE MOVIE

Thirty years after the conflict, on January 20, 2002, Bloody Sunday the movie, starring James Nesbitt, premiered at the Sundance Film Festival, to wide acclaim. In the following interview, Nesbitt, who won a British Independent Film Award for Best Actor for his role in the film, talks about, his decision to play Ivan Cooper, the shirt-factory manager, and local politician who was involved in the civil rights movement, and what he hoped the movie would accomplish.

Nesbitt, like Cooper, is a Protestant, and in accepting the role he knew there was a chance that he would be seen in his own community as “going over to the other side.” Indeed, when we met up in New York following the release of the film, that he had received death threats as well as praise for his performance.

“I think Protestants have walked away from it for years,” he said. “No one wanted to own Bloody Sunday. As [producer] Jim Sheridan said, ‘The Irish don’t forget and the English don’t want to remember it.’”

Nesbitt grew up the son of a schoolteacher in rural County Antrim, near Ballymena, the only boy with three older sisters. His family is very proud of their Protestant culture, but he says that his father is “an egalitarian.” In fact, as a youngster Nesbitt was a boy soprano and his father used to take him to sing at Irish Feiseanna (festivals). He also took piano lessons in the local convent.

Despite his own exposure to Irish “Catholic” culture, he said there was “a great sense of denial about what was going on” in the province.

“The reality of life in Northern Ireland,” said Nesbitt, who was only six years old when Bloody Sunday happened, “is that if you were Protestant you learned British history and if you were Catholic you learned Irish history in school.”

The movie was a rite of passage for him – a growing up.

“I come from a generation in Northern Ireland where we sort of didn’t want to acknowledge the Troubles in our country. I was almost shamed by it when I read the script, and I couldn’t not do the movie.”

And so began what Nesbitt describes as an extraordinary journey, one that became much more than movie-making. “It was a personal odyssey,” he says. “I felt I was making a film about my country, a country that I love and was trying to make sense of. It made me see for the first time why all these terrible things have happened.”

He described the shoot as “an emotionally wrenching experience,” but said his respect for British director Paul Greengrass saw him through.

Greengrass was the first journalist to film inside the Maze Prison while covering the hunger strikes in 1981. He had read Don Mullan’s Eyewitness Bloody Sunday and decided that he, as a British person, had an obligation to explore this side of modern British/Irish history.

Nesbitt felt the obligation too, but he admits that he couldn’t have undertaken the project without the support of his wife and parents, who while wishing he was doing a movie about “some of the terrible atrocities that have been visited on Protestants,” supported his decision to take on the role. “I said, ‘Trust me, I believe in it. It’s an important thing for me to do.’”

On a professional level, Nesbitt says that he came away from the movie with a newfound respect for his craft. “It was thrilling and moving and so hard, but so validating,” he said. “At the end, I walked away from it and thought, ‘I can see where this job [of being an actor] does have some worth.’ I couldn’t pretend that acting was just this thing that I didn’t take too seriously anymore,” he said. “It required constantly living in the moment. We had to be able to put ourselves down in 1972 and be able to cope with everything.”

Greengrass forced Nesbitt to look at the daily rushes to show him when he was in the moment and when he wasn’t.

“We improvised a lot. You know, improvising political dialogue is not easy. For instance, on the back of the civil rights lorry, you didn’t know until the moment what was going to happen. People shouted different things at me, and I had to respond. And I had to do so much research [in order to respond properly.] I read a lot of the evidence that had been amassed on Bloody Sunday.”

Nesbitt also sought out the families of those who had been shot, having first familiarized himself with as much personal information as he could about the victims. He went and met Ivan Cooper, whose spirit was broken after Bloody Sunday, which marked the end of the civil rights movement and a move towards the IRA’s violent opposition to British rule.

Nesbitt’s hope is that the movie will help the healing process in Northern Ireland. “All my adult life, there was the Troubles. That was the backdrop of my life. Bloody Sunday was an opportunity to be involved in something that could be a part of the peace process in Northern Ireland.

“So many great steps have been made now. There’s still a long way to go, but the very thing that Ivan Cooper marched for along with those 20,000 people 30 years ago, is exactly what we’re standing for now – inclusion and civil rights. Paul Greengrass once said to me, ‘If Bloody Sunday can be a pebble in the wall of peace, we’ll feel that we’ve achieved something.’”

Read more about Ivan Cooper who passed away on June 26, 2019 at age 75.

Read Tom Deignan’s article, The Making of Bloody Sunday.

Leave a Reply