It’s early morning in the upscale café in the Four Seasons Hotel in Manhattan. Not my usual hangout, but having spent two days immersed in Brian Keenan’s book An Evil Cradling, the story of his almost five years as a hostage in Beirut, it seems fitting, since it’s my treat, that we breakfast in nice surroundings.

Seated opposite me, barely touching his pancakes, Keenan, 58, speaks in a soft Belfast accent. He is in good spirits, but a little abashed at the reaction to a talk he gave at a conference the day before.

Many of the audience members had been moved to tears by his stories, and his vision of a united Ireland, which he said “must be a place of imagination, intellectual not political.” He received a standing ovation.

Asked why he got such a reaction from the 700 plus audience, gathered for a Unite Ireland Conference hosted by Sinn Féin, Keenan explains: “When I was asked to do it I said yes instinctively. When I sat down to prepare for it I realized, holy God, how can you take five centuries of trouble, despair and a bloodbath and bring it to a place in fifteen minutes? And so I had to go back to my stories. I knew it had to be a very personal thing because we’re all engaged with this personally whatever our politics might be.”

The stories that Keenan told – about the taunting of the only Catholic boy who lived on his street; about an old Protestant woman crying on learning of Bloody Sunday; about a Catholic barman breaking in a pair of shoes for Keenan’s father so he could walk more easily in a July 12th Orange Parade – were very effective in putting a human face on the Troubles. Pete Hamill, the American writer who moderated the conference, and talked about people like his own Belfast-born parents “being hurt out of Ireland,” was among those visibly moved by Keenan’s stories, which are now included with other stories in a newly released memoir of Keenan’s childhood, I’ll Tell Me Ma.

Much has been made of the fact that Keenan was born into an Ulster Protestant family and brought up in a strict sectarianism culture. He explains why he escaped contamination.

“My dad was an Orangeman but he was a socialist in his own way, he had very strong views on it. He was the most unusual Irishman, I can tell you. Well, he was a Mason. My mother had a kind of Mother Earth thing going. She was always doing things for the neighbors. You know the way working class women do.” She also sent the minister “the hell away” from the door when he called to complain that the young Keenan was asking too many “awkward questions” at Sunday school. “I didn’t have all that church contamination. My father and mother whenever [questionable] things came up weren’t too taken aback, and neither was I, consequently.”

Asked about his story of stopping his buddies from taunting a Catholic boy, he said: “It was this kind of intuitive thing that kids have about what’s just and what’s fair. And [the boy’s] sense of alienation mirrored something that was articulating back to me in an unspoken way. There were lines of psychological and emotional connection. One was about justice and one was about being different. And he mirrored me and I mirrored him and it couldn’t have been a reason thing at that age.” Brian explained further: “I suppose I always was a reflective child. I wasn’t like the other kids. I had what’s called buck teeth, very prominent teeth. So I got called names like Bugs Bunny, which didn’t seem to bother me. Your mates are still your mates (‘Listen, Bugsy’). It really only bothered me once girls came onto the scene ‘because who’s gonna kiss you, man?’ And I didn’t play football and if I was picked I was the last person picked to play. So I read books.”

The first book he read was Jack London’s Call of the Wild. And half a century later he says he can remember it. “I was about nine when I read it. While my mates were out kicking a football or robbing orchards I was reading Jack London and running with a pack of wolves. So I suppose I was quiet, reflective in that sense. I got a lot of compensation out of taking myself other places or going other places imaginatively. Imagination was always a buoyant lifebelt I wore.”

Keenan left school at fourteen to become a heating engineer. Later he decided to become a teacher and enrolled at university. In 1986, at age 30, he found himself at loose ends; his friends were all getting married, and he decided that he needed a change of scene. “I was tired of the intransigence, the backward mess, the terrible sense of stoppage, politically and socially. I’m saying that about myself on a personal level too. I wasn’t married. I didn’t have a job.”

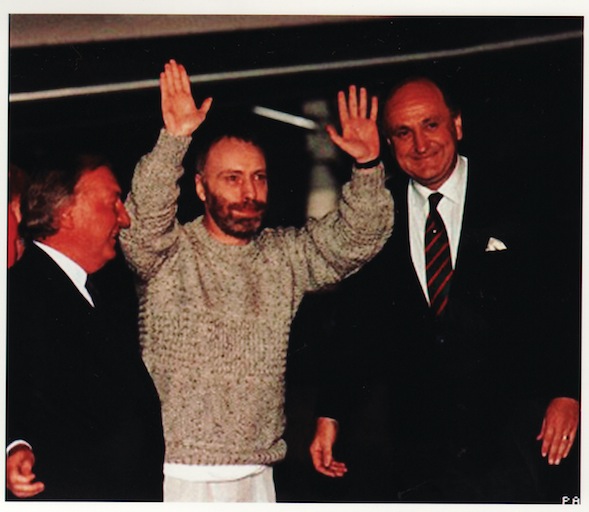

He applied for a position to teach English at the American University in Beirut and was accepted. Four months into his contract, in April 1986, he was kidnapped by fundamentalist Shi’ite militiamen and held hostage, apparently because they believed he was British. Despite pleas from the Irish Embassy in Beirut (he was traveling on an Irish passport) and an active campaign put together by his two sisters back in Belfast, he remained hostage for almost five years until he was finally released into Syrian custody in August, 1990.

Needless to say, the Brian Keenan sitting across from me is different from the image of the emaciated hostage that went around the world when he was released. Today, he’s a fit-looking man, a badly healed broken nose the only remaining evidence of his physical torture.

His boyhood imagination became a valuable resource to draw on during his internment. He recalled books that he read and movies he’d seen and rewrote the endings in his head. As a child he had explored Belfast on his own, and as a teenager he’d hopped on trains, and in the darkness (for most of his internment he was blindfolded and chained) he recalled those journeys, which helped but didn’t always keep the insanity at bay. He explains: “You know that famous line from Milton ‘A mind is its own place, and in itself, can make heaven of hell, a hell of heaven’ – that’s what happened. The mind can take you places you really don’t want to go. It was very hard to deal with, and maybe the only way I could find to deal with that was to say, [‘It’s] okay if I’m going insane. So I’m going to go take myself there and I’m going to become more insane than sanity itself.’”

After several months in isolation Keenan was joined by John McCarthy an English journalist, who had been kidnapped shortly after Keenan. McCarthy recalled that first encounter in an 1999 interview with The Independent newspaper. “After a few hours we were laughing a lot. That was certainly a great relief. What surprised me was Brian’s reaction to the guards. He wasn’t going to take any nonsense. I was impressed, but also slightly frightened by it. These are the guys with the guns. We’d heard them beating people up, even killing someone. When he started standing up to the guards, saying ‘No, I’m not going to do this,’ or, ‘You’ve got to bring us food,’ I’d be thinking, let’s back off a bit. But it was very encouraging to me. . . . What Brian taught me was if you don’t address fear and fight it, then you’re lost.”

The two would become each other’s “buoyant lifeline.” Chained and blindfolded much of the time, held in confined spaces and moved 17 times in the dead of night tied up under trucks and in the boots of cars, suffocating from the tight mummy-like bindings, they were always relieved to find that they were still together when they reached their new location.

“He would be aware of when I was getting very frustrated or unfocused. He would use the medium of humor,” he said of McCarthy. And in turn, Keenan would do the same for him. “I knew intuitively when he was going down, he didn’t have to say anything or do anything. I knew when he was entering a dark place.”

The fact that McCarthy was English and Keenan was an ardent Irishman helped. “If I had been with somebody who was like myself, time would’ve passed very slowly, because you need validity of who you are through another person. So I would’ve got less validation because I would’ve had less to give.

“McCarthy’s difference meant he had more to give and I had more to give. The other curious thing is, John said the public school he went to, most of the lads either went to university or else they went into officer training in the British Army. He said at one time, ‘I could’ve been pointing down a gun at you or you at me.’ And we laughed about this. It made me banter with him like hell. And he would banter back, saying, you fucking Irish baboon. We were able to play – you know how important play is to kids, it takes you out of where you are. Well, that’s what happened. Two grown men had to learn to play again. He had just assumed I was an Irish Catholic nationalist, and about a year down the road I said, ‘John, I’m a Protestant’ and he said, ‘What?’”

A review in the English press said of An Evil Cradling, if you ever want to understand the Irish question you should read the story of Brian Keenan and John McCarthy.

“It is about validation,” Keenan said. “You need the other to validate who you are, what you are, or what you might aspire to be. You need another to listen to what you’re saying and you need to do the same with him.

The point he’s making is that a united Ireland “has to be a Republic of the heart, of the mind, of the word. It has to be a united place imaginatively brought together. Whatever might articulate itself in political terms or historical terms or visionary terms, I believe it’s the imagination that will create this [united place] and if you want imaginative Ireland you must go there first. Then begin to articulate it to the others.”

Despite the destruction that the Troubles brought to the North, in the scale of things, it’s not as bad as other places Keenan has seen. “I’ve been to the Middle East, and other troubled places. And when I put them all together, the North doesn’t weigh too heavy, in a comparative sense. We’re not psychically hurt to the degree of some other people. I’ve walked through some places and Jesus, you know, I don’t know if those people can be rescued, if their humanity can be pulled up out of that very, very dark destroyed place that they are in and give them a sense of identity and purpose. At least we didn’t lose that,” he said.

There’s a pivotal moment in Keenan’s captivity that he writes about in An Evil Cradling when he realizes that Said his tormentor is himself tormented. Brian explains: “Said is praying and he’s annoying me with his prayers because he’s right on the other side of the sheet [dividing McCarthy and Keenan from their captors]. And he would do this because he knew it was like putting a hot poker inside me. Now, I would have cut Said’s throat and smile while doing it because he was not a pleasant man, he got off on torturing you. But [this one night when he was praying] he started sobbing and I realized, this man is genuinely disturbed. I knew that place because I’d been there. My instinctual reaction was that I would reach out and hold him, but I couldn’t because he was on the other side of the wall. In some strange way, Said knew that I knew. It changed things. No words were ex-changed, but Said knew that there wasn’t anything more he could do [to me].”

Asked if he truly believes, as he had said, that the only way out is love – it’s like a stepladder out, he said: “But that’s very hard. It’s really hard for people to climb out of their own sense of dislocation or dispossession or to fight their way out of it. For me the true revolutionary is really a lover and not a fighter. Because the object of his concern is all of the people — not all of the idea. There’s nothing in our DNA that marks you as terrorist. So people become that for some reason, and you’ve got to find out the reason.”

Given all that happened to him, Keenan seems remarkably normal. How had he managed to go on with his life while others did not? Hostage Frank Reid, taken at the same time, never recovered and died a broken man.

“There’s a term for coming back to earth, a kind of reentry. That’s the way I thought of it. Or like coming up from a deep dive, when you’re taken to a decompression chamber for a while and then another one, and that’s the way I kind of unconsciously chose to work this through. I refused to talk to a psychiatrist. I don’t need anyone to tell me what’s wrong with me.”

He signed himself out of hospital after 10 days and headed to the West of Ireland by himself. It was something he had promised himself he would do.

“I found an old cottage, and as much as I could do with my own hands and labor I rebuilt it. I wrote a book – it wasn’t supposed to be An Evil Cradling. But it’s what I wrote. And the other thing [I wanted to do] was to paint because for five years I looked at a concrete wall but I hung pictures on that wall which I created out of my head. I haven’t done that yet [painted]. I have the colors and the brushes but there’s part of me that says the pictures in my head are more perfect than if I was to try to put them on canvas,” he said.

The image of Keenan as a loner who left Belfast – because all his friends were getting married and he was not in a relationship (and in An Evil Cradling he wonders if he will ever have children) – began a fast fade on a day soon after his release. Keenan was still in hospital when a physiotherapist named Audrey Doyle brought him down to the gym, had him sit on the floor and tied a cord on his ankle and the other end to a bar on the wall. It was for resistance training because he had lost so much muscle tone during his confinement, she explained. Shackled thusly, he looked up wide-eyed at her and the incongruity of the situation hit her. She burst out laughing. “She’s inclined to do that whenever she’s nervous” he said.

He had been worried about affection – giving it and receiving it. For so long the touching had been aggressive beatings – but he found himself drawn to Audrey, perhaps because she was the first one to touch him in a physical way after his release. They dated for a couple of years before marrying and now have two young sons, Cal and Jack, 9 and 11.

He admits that he had to work up the courage to ask her out. But the one thing he had learned during his confinement was to push through his fear. “I have this absolutely firm belief, which I discovered the importance of when I was locked up, that choice is the crown of life. If you don’t activate choice, you’re not living. You’re just breathing in the antithesis of what life is,” he said.

Keenan followed up An Evil Cradling with a book called Four Quarters of Life in which he explores Alaska, object of his fascination which began as a small boy when he chose Call of the Wild from the school library. It’s a soulful book, beautifully written. He also co-wrote Between Extremes with John McCarthy, about a trip they took together to Patagonia and Chile where they crossed the Andes on horseback.

The reasons Keenan made those journeys was not only to pit himself against the wilderness while he “physically still could” and “find that part of himself that was still unknown,” but because he wanted his sons to know that their dad was not just an ex-hostage, that they had lived in Alaska when they were young where Cal learned to walk.

It’s why he takes them on trips to the west of Ireland “to show them a place of magic when they are young that will always be with them.” And it’s why he took them on a recent trip to Lebanon where he was kidnapped, to show them that it is not a place of evil.

It occurs to me that had Keenan not been a hostage he would not have written these wonderful books.

“Well, that’s true,” he said. “[My captors] didn’t give me any books until halfway through the third year. Then they gave me a copy of the Koran, which I read. There’s a part of the Koran where the words ‘an evil cradling’ come from where the prophet is talking about the taking of captives. And the prophet says to his followers, give the Koran to the captives so that they take with them when they go more than was ever taken from them. I’m not religious – I don’t believe in that hocus – but that’s what happened. I came back with more than they ever took from me. I came back with a wealth of riches.”

What a lovely story. I must now read “An Evil Cradling.” It’s wonderful what some people can do with a terrible experience that benefits the rest of us by deepening understanding and empathy. Thank you, Brian Keenan. And Patricia Harty for writing about him.