On November 2, 1759, a veritable riot broke out along several blocks of lower Manhattan. The target of the torch-bearing crowds was a man deemed to be a “rogue” and informer named George Spencer. Spencer survived the crowds’ wrath, though he was banged up with bruises and cuts. What Spencer – or the mob – did not know was that they would be swept up into events which would have ramifications across the British Empire, which, in 1759, included New York and all of the colonies up and down the eastern seaboard of what is now the United States.

Within 15 years, those colonies would, of course, revolt, an event marked for the 239th year this past July 4.

The heroes of that American Revolution are well known, as are many of the events in the 1770s which led to the colonists’ famous Declaration of Independence.

What is less well known is that events stretching as far back as the 1750s had planted the seeds of American Revolution. At the center of one key conflict was a small but influential group of Irish merchants and traders who had settled in New York. They were there – as most people in 18th-century New York were – to make a buck.

But if, along the way, they also hurt the British Empire, well, that probably didn’t bother them too much.

The French, The British, The Irish

How did these Irish merchants hurt the British? They continued to trade with the French in the 1750s, even as tensions between Great Britain and France eventually led to the full-blown conflict Europeans call The Seven Years’ War and Americans know as the French and Indian War.

British colonial forces had tried to stop the commercial activity of the Irish merchants by passing numerous laws. The British hoped to keep key goods out of the hands of their enemy, the French. And yet, many merchants in New York continued the clandestine practice of trading with the French. They skirted laws by using faked records, by making stopovers on neutral islands or even routing goods through Ireland.

The Irish – many of whom viewed France as a sympathetic Catholic ally going back to the Protestant Reformation – continued to trade with the French, thus undermining the British war effort, as the French and Indian War raged in the 1760s.

True, the war ended in 1763 favorably for the British. “The British Army had routed the French from Canada and the American colonies,” Don Cook writes in his book The Long Fuse: How England Lost the American Colonies, 1760– 1785.

However, the war had far-reaching, unforeseen consequences for the British. “America was also imbued with a heightened sense of independent political and economic strength and a vision of expansion and destiny. The colonies simply wanted to be left alone to run their own affairs and to grow and expand on their own…. Thus the Seven Years’ War laid the long fuse that would eventually splutter into revolution.”

So, perhaps every July 4, we should not only remember Ben Franklin and George Washington, but also Waddell Cunningham, William Kelly and Thomas Lynch. These were some of the merchants who – whether they knew it or not, whether they did it for independence or simply to make a buck – laid the groundwork for the American Revolution in New York in the 1760s.

Planning a Riot

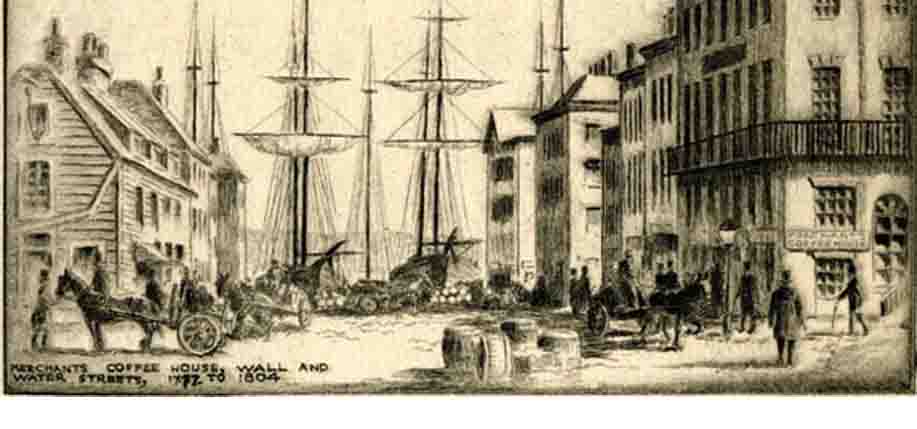

The aforementioned riot of November 2, 1759 was actually planned the evening before by a group of Irish businessmen who met in the Merchants Coffee House, located not far from the East River docks in Manhattan.

As Thomas M. Truxes notes in his fascinating new book Defying Empire: Trading with the Enemy in Colonial New York (Yale University Press), the Irish merchants had identified Spencer as a rat who had told British colonial authorities about lucrative trading the Irishmen were engaged in with France. Tensions between France and Britain had already exploded into full-blown war.

Thus, the Irishmen were not merely violating some commercial laws. In the eyes of British colonial authorities, this trade was treason.

Yet, it was also very lucrative. That’s why men such as William Kelly, Jonathan Lawrence, Thomas Lynch, James Thomspon, Thomas White and (as Truxes calls him in his book “the de facto leader of the city’s Irish merchants”) Waddell Cunningham met in the Merchants Coffee House. They knew that Spencer had informed.

“Rum and punch flowed,” Truxes writes, “as the group concocted an elaborate plan that would ‘render [Spencer] infamous and invalidate his testimony, and at the same time be a warning to others not to dare to make farther discovery for the fear of like treatment,’” writes Truxes, who teaches in the Irish Studies Department at New York University.

Cunningham and the Irish merchants confronted Spencer. He would not recant his testimony, so they persuaded one of Spencer’s debtors to call in his loan. Spencer was arrested.

As he was being walked to jail, the Irish merchants got the word out that a rat was being paraded through the streets. Swarms of people came out to hurl objects and insults at Spencer.

If anyone doubted the influence of Cunningham and the Irish merchants in colonial New York, they no longer did.

Tied to the Elite

These expatriate Irish merchants “benefited from their close ties to New York’s political, social, and economic elite,” Truxes writes. “George Folliot, for example, a Derry native who emigrated to the city in 1752, married the daughter of…a high-ranking customs officials and the brother-in-law of Alexander Colden, son of Caldwallader Colden, president of the Governor’s Council and later lieutenant governor.”

But this position of prominence was now being threatened, as British authorities aimed to crack down on Irish-American trade with the French.

Things only got worse for the British when it became clear that Spain – another Catholic nation – would be entering the Seven Years’ War on the side of France. The British soon began making mass arrests in New York. They picked up alleged French spies, as well as nearly 20 men accused of “illegal correspondence with His Majesty’s enemies.” Among them were Irish merchants Waddell Cunningham and Thomas White, who were eventually found guilty and ordered to pay what Truxes calls a “staggering” fine. The verdict “had an unsettling effect on the trading community in New York. In the weeks that followed, a long shadow fell over the city.”

Test Run for Revolution

Cunningham, who had a plantation in the West Indies called Belfast, and numbered among those who benefited from slavery, eventually left the colonies. He returned to Belfast where he tried but failed to establish a slave trading company. One reason was because the abolitionist movement was strong, and groups such as the United Irishmen, who supported Irish independence from Britain, opposed all forms of subservience. He became a prominent member of the Irish business community and was even elected to the Irish House of Commons in 1784, before dying in Kockbreda, Co. Down in 1797.

It seemed, in the short run, that the British had effectively solved the problem of the Irish merchants. But Cunningham and his colleagues had exposed a crucial weakness in British supervision of the colonies. Yes, the British emerged from the Seven Years’ War strong. But, in doing so, they also were forced to use a heavy hand on colonial merchants. This became an increasingly common gripe among colonists, particularly as they were forced to pay more and more of the debt incurred by the British while fighting the war.

There eventually came a point where the colonists wondered why they needed to maintain their relationship with the British. That is what led to the American Revolution. Of course, this likely would have happened whether or not Waddell Cunningham and his cronies defied the British and traded with the enemy. Still, their actions served as a kind of test run for the American colonists. Whether they did it out of bravery or greed, Cunningham and his fellow Irish merchants wrote one of the earliest chapters of Irish-American history on the crowded streets of New York in the 1760s.

The cornerstone of your respective trading approach is a breeze

to see. We appreciate you for conveying this with me

today.