An exhibition at the Morgan Library attracts Oscar Wilde enthusiasts.

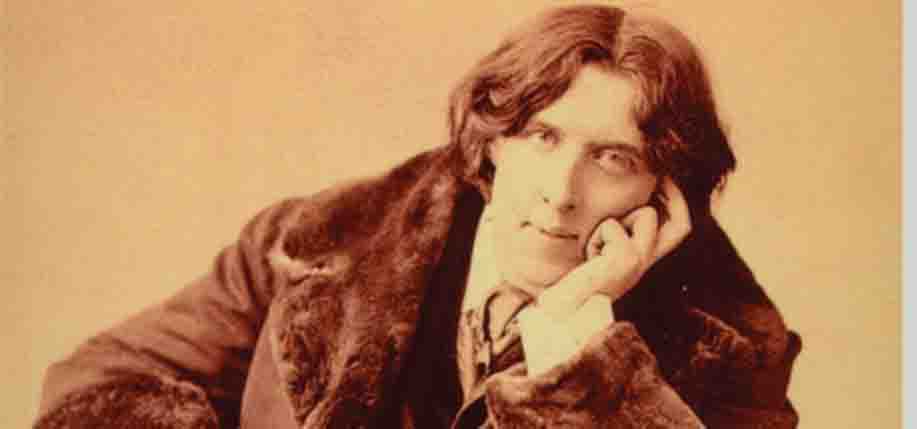

Expensively dressed, impeccably mannered and gifted with a voice so beguiling his contemporaries marveled at him, Oscar (Fingal O’Flaherty Wills) Wilde was also one of the wittiest men of his age. Even today, just to hear his name is to anticipate delight. That’s why his cult, which began in his own lifetime, shows no signs of ever diminishing.

This month, in an exhibition that seems calculated to attract every Oscar Wilde enthusiast in America, the Morgan Library and Museum in Manhattan will exhibit a selection of the Irish writer’s most important manuscripts and letters. But this isn’t just another stuffy museum piece featuring a more than usually compelling Irish writer. This time the Morgan can boast of a dramatic first: the whereabouts of this beautifully bound collection was unknown to scholars for over half a century.

Bequeathed to the library in December 2008, the current collection comprises nine manuscripts of Wilde’s poems and prose pieces and featuring four important letters that illuminate the life and work of the dramatist, aesthete, wit, and self-proclaimed “lord of language,” making the exhibition one of the most important illustrations of the breath and scope of Wilde’s artistic achievements to be seen in America this decade.

The Morgan Library, one of the most beautiful private libraries in the world, is the perfect venue to appreciate Wilde’s art and life. Totaling at just over fifty handwritten pages, the expertly crafted red-leather-bound volume of some of Wilde’s most important manuscripts and letters went on public exhibition on April 17, 2009 and can be seen until to August 9, 2009, as part of the Morgan’s exhibition Recent Acquisitions, which will highlight important additions to the institution’s holdings in the last five years.

Why does Wilde still matter? Because the sheer force of Wilde’s all-electric personality jolted Victorian society out of its complacency, a remarkable achievement, and each time they thought they had the measure of him he increased the voltage. Wilde was a depth charge, a modernist dressed like a romantic in a faux romantic age. The Morgan’s exhibition will demonstrate that there’s much more to Wilde’s legacy than fancy knee-britches and verbal pyrotechnics.

Of special note in the new exhibition is the earliest surviving letter from Wilde to his aristocratic lover Lord Alfred Douglas, known as “Bosie.” Written in Wilde’s distinctive rounded lettering, it shows how smitten he really was with the whey-faced, flaxen haired youth. “I should awfully like to go with you somewhere where it is hot and colored,” Wilde writes, in a blatant attempt to arouse Douglas, but for a modern reader it produces a burst of knowing laughter. The overheated prose demonstrates Wilde’s growing obsession; it is also a kind of unknowing dress rehearsal for what was to follow – Wilde set out to conquer but was himself harpooned.

It’s harder from our own standpoint in time to remember this, but Wilde’s improbable affair with the English upper crust was once thoroughly requited. Physically exotic to look at (one observer once compared him an Aztec), hailing from an unfashionable colonial backwater and yet somehow a better speaker than all of his contemporaries, Wilde had an emigrant’s skill of beating the locals at their own game. An outsider who became the ultimate insider, he dined with royalty and male prostitutes in the same evening, until Victorian society asked him to choose, and when he refused to, they pounced.

But Wilde was modern in a way that London society had never seen. He made the Prince of Wales laugh, he delighted rent boys; he knew every palace and quite a few of the back alleys of Victorian London and he saw no distinction between them. “It is absurd to divide people into good and bad,” he once wrote. “People are either charming or tedious.” That was precisely the sort of crack calculated to enrage the moral scolds who had disapproved of him going all the way back to his college days in Oxford. But it also betrayed Wilde’s democratic spirit, because for all his social climbing, he was never a snob.

In a marvelous letter on display in the current exhibition Wilde writes to one admiring reader, a Mr. Bernulf Clegg, who has asked him to outline his philosophy of art. Wilde’s answer is so indulgent and delightful you can almost hear him responding in his own voice:

“My Dear Sir, art is useless because its aim is only to create a mood. It is not meant to instruct or to influence action in any way. A work of art is useless as a flower is useless. A flower blooms for its own joy. We gain a moment of joy by looking at it. That is all that there is to be said about our relation to flowers.”

Like James Joyce, who understood Wilde’s challenge to his contemporaries much better than most, Wilde held his own (brightly polished) mirror up to the cruelty lurking behind the throne of the British Empire, frequently enraging the people he most wanted to court. And the greatest tragedy of his all too short life is that Wilde was not given time to reconcile his own warring impulses in his art.

For proof of his conflicted attitude toward the Victorians you just have to look at the larger-than-life names he gave most of his characters: Algernon Moncrieff, Gwendolyn Fairfax, Miss Laetitia Prism, Lady Augusta Bracknell, Lord Henry Wotton, Basil Hallward, Dorian Gray. This is the writer-as-costume-maker, because for Wilde the lords and ladies of English society were as unreal and exotic as the caliphs of Baghdad. His gently mocking stage names are part of a consistent pattern in his art, a satirical undermusic, a Celtic note that is rarely remarked upon, because like so many of his best jokes they only register with those who can actually hear them.

All his life Wilde’s suspicion of authority, and his half playful half serious desire to unmask hypocrisy, particularly when it came wrapped in the garb of English imperialism, keeps breaking out, even when he knows it would be wiser to say nothing. It’s a distinctly Irish reflex, that satirical feint and jab, and Wilde couldn’t help himself; his own divided nature was overwhelming, he genuinely wanted to trounce the thing he loved.

As he had already powerfully demonstrated in plays like A Woman of No Importance and the poem The Ballad of Reading Gaol, the man who achieved lasting fame as a sort of high brow humorist was also was on his way to becoming a tragedian of real stature, but his trailblazing path was cut short when Edward Carson’s shadow fell across it.

There’s a terrible clanging irony in the fact that it was Edward Carson, of all people, who sealed Wilde’s fate. At Trinity College Dublin, where they were exact contemporaries, Carson was continually runner up to Wilde’s first prize in every academic contest the two entered. Wilde was the son of the fiery Irish nationalist poet Speranza (Lady Jane Wilde). Carson was raised in a staunch Presbyterian home and would later sign the famous so-called blood covenant that would divide Ireland as it moved toward Home Rule. Wilde was an artistic genius, Carson was a shrewd prosecutor.

Wilde died penniless and alone in a third rate Paris hotel in 1900, and in May of that same year Carson was appointed Solicitor-General for England and received a knighthood. England has always rewarded its gate keepers: Carson is one of the few non-royals to have been given a state funeral by the United Kingdom, the funeral taking place at St. Anne’s Cathedral in Belfast in 1935.

In America, where another version of the same Puritan legacy that Wilde pushed back against in his art and life still rules, he has been continually misprized by writers and academics who should know better. But to this day there many here who are still tempted to see his reputation as a wit as a sort of proof of his light weight achievements. That’s why Declan Kiely, the curator of the current exhibition at the Morgan, and an Irish Studies scholar, should be thanked for his sensitivity and insight in programming this unmissable show. The business of rescuing Wilde from the short sighted and clumsy hands he fell into (including Bosie’s, who destroyed most of his letters) is still ongoing.

The Morgan Library and Museum is located at 225 Madison Avenue in New York City.

Leave a Reply