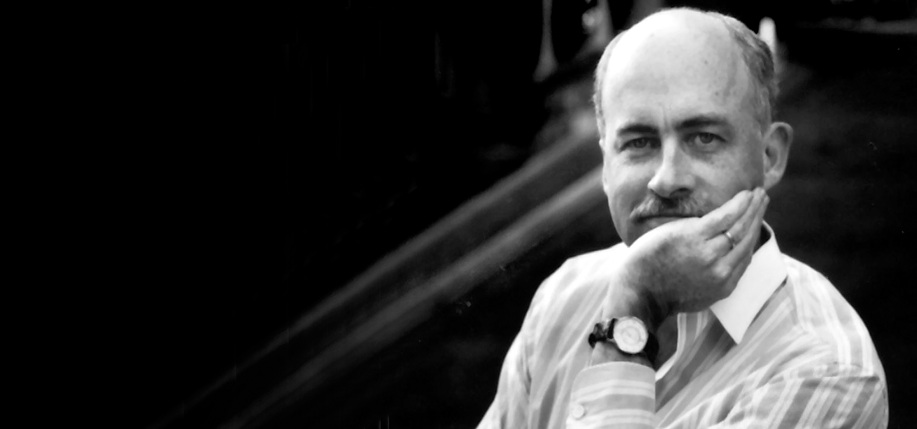

A crowd of admirers awaited Peter Quinn when he came to Glucksman Ireland House, NYU on October 16th to launch Overlook Press’s new edition of his award winning novel, Banished Children of Eve, the tale of Irish-Americans in New York during the Civil War. Many had read the much praised novel that celebrated writer William Kennedy called “terrific … an ebullient mingling of fiction and history,” and the esteemed author Thomas Flanagan judged “one of the very very best of modern historical novels.”

Professor Joe Lee, Director of Ireland House, said Banished Children of Eve showed how a historical novel could be significant in both literature and history. “It’s a landmark book,” he said. “Peter Quinn was able to blend history and literature, to transcend them into something beyond them both.”

In his talk that followed, Peter Quinn blended humor and erudition to elicit both laughter and thoughtful attention from his audience. He will be speaking in various venues, so readers can consult the schedule on the Overlook Press website for the chance to hear him.

In this interview, Peter Quinn went behind-the-book to explore the process of writing Banished Children of Eve and his non-fiction exploration of Irish-American life, Looking for Jimmy.

“I grew up in an Irish-American family in the Bronx, but we really didn’t know that much about Ireland, and we didn’t know that much about ourselves. My first ancestors came over in 1847. I had this general story of our family beginning on the Lower East Side, but I never thought of it as anything very epic. Ireland was way in the background. We were more Catholic than anything else. That’s what it meant to be Irish in the Bronx: identification with your parish, your school, knowing you were Irish but not knowing much about it.

“In the sixties I was a Vista volunteer in Kansas City, an education teacher, thinking I would go live in California. It was the first time I ever turned around and said, ‘I’m leaving all of this – but I don’t know what it is.’

“Everything was going down in the Bronx in the ’60s. People were moving, the buildings were burning down, the church was changing. And I thought, I’ve got to go back and find out something about it.

“So I studied history at Fordham – got a doctorate eventually – with Morris O’Connell, who was Daniel O’Connell’s great-grandson. I learned a lot of Irish history, and then went over to spend a semester in Ireland at University College Galway.

“I was about to finish my dissertation, but was on this demographic curve and all the jobs had gone away. So I was writing articles for America, the Jesuit magazine. Kevin Cahill, Director of the American Irish Historical Society, saw one and gave it to Governor Hugh Carey. He hired me as a speechwriter.

“Working in Albany, I started to think about writing a history, not of Ireland but of the Irish coming here during the Famine – what it was like, a social history like the book Irving Howe wrote, World of Our Fathers, about the Jewish experience.

“I began to research that, looking at housing reports, police reports, and came upon the Draft Riots, this great explosion, which I immediately connected with the Famine immigration. Then at one point I realized that I didn’t want to talk about the great social forces – I wanted to talk about individuals. So then it was on to try to write fiction.”

Was there any individual or story that moved you to write this book?

“I discovered that Stephen Foster, the progenitor of the American song industry, committed suicide, I’m sure, on the Bowery in January of 1864. And I realized the man who wrote ‘Oh Susanna,’ ‘Gentle Annie,’ ‘Hard Times’ – some really great first American songs — was down there during the Draft Riots.

“I stood outside the hotel on Broadway and Bayard, where he had died. I thought, ‘I know who he is and I can hear his voice.’ I had the idea for the book in 1982, then I researched until 1988. I started writing on Columbus Day, 1988 – twenty years ago today. I remember because I finished three and a half years later on the Feast of the Epiphany.”

What was that process of writing the novel like?

“I never start with an outline. Banished Children, Hour of the Cat, and the book I’m working on now all started out in my mind with two people having a conversation. I have the setting, I know what year it is, and they start talking. The plot comes out of that. There were moments I had to wait. I would write and realize I don’t know what they’re going to do next, but two novels later they’ve never let me down. They’ll tell you what they’re going to do.

“My experience of writing is that there is no one way. What I think you have to do is make the time, a time when you show up. You don’t know if you’re going to get one page or two or nothing, but you’re there for them. The rest is mystery.”

How did this mystery affect you?

“The deeper I got into Banished Children of Eve, the more I saw that the Irish Famine immigration was an epic story of the movement of agrarian people who moved into cities — which is still going on all around the world. My family had been part of this. And I said if I get everything wrong, but people come away with a sense of this epic dimension to Irish-American history, then I’ll feel I have succeeded.

“We take so much for granted: Our ancestors came over and built all these schools, churches, hospitals, the unions, the Democratic party – a whole world. But they had to build it all from nothing. There were a lot of reasons why they should have fallen apart or just disappeared. You know, if it were just a matter of skin complexion they could have become Protestants, but something deeper and more complex was going on.”

Could you talk about the complexity?

“Once the immigrants stepped off the boat in America, they were no longer just Irish. They had to deal with a whole different society. The culture of the diaspora is not the same as the culture in Ireland. It’s rooted in that but it becomes something else when it comes here. An urban culture is created.

Looking for Jimmy is the non-fiction handbook to go along with Banished Children. In the book, I say one of the reasons the Irish were able to have such an impact on the urban experience was because they had to make it up. They didn’t come over with useable habits or customs. Everything they’d come to know in Ireland was useless in New York and Chicago. So the whole thesis of Looking for Jimmy is that they’re making up an urban personality because they don’t have anything else to fall back on.

“The Irish felt safe in cities. My ancestors never wanted to see the land again. They came out of the worst agricultural trauma in 19th century Europe. A million die and two million leave? Get me to the city. Yet they found a deeply ingrained prejudice in Anglo-American society towards the Irish. They weren’t taken seriously. There’s a line by Samuel Eliot Morison in the Oxford History of the United States, published in 1961, I believe, that I read in high school. It said, ‘The Famine Irish made surprisingly little contribution to the economics or culture.’ Yet look at popular entertainment: They made a tremendous contribution, beginning with the minstrels theater and traveling shows. And the economic contribution — who does Morison think dug the canals, the reservoir; who dug the Erie Canal? Yet a leading American historian could write that the Irish almost didn’t exist.

“The Irish were looking for survival. They built political machines and out of those machines came the first social welfare system – the use of public funds to support citizens. “Little or no effect” – how wrong that was. Yet I was going to a Catholic high school in the Bronx in the 1960s and I’m told to read this book and it goes unchallenged.”

Why was that view not challenged?

“I think so much of Irish-American experience is getting on with it, not stepping back to take an honest look at it. Until very recently the main concern of the Irish-American was just taking the next step. The Irish peasant society dissolved when the people came over here. All those institutions that we take for granted — the Catholic parishes, the labor unions — are all embodiments of efforts to survive that trauma. So we didn’t look back. We created parallel social institutions.

“The Irish responded to the ferocious anti-Catholicism they found in America by saying, ‘We’re forming our own schools. We’re not letting you form our children. We’ll form them in their own culture, then they’ll go into America.’

“My parish in the Bronx, St. Raymond’s, had a church, a boys’ grammar school, a girls’ grammar school, a rectory, a brothers’ house, a convent. The amount of money that people poured into those institutions, as well as womanpower and manpower –- so much volunteer labor. This tremendous outpouring to create their own hospitals, their own schools is a pretty amazing story.

“My mother went to Holy Angels Academy in Fort Lee, New Jersey and the nuns there got their master’s degrees at Columbia — women, in 1920. Think of it.”

Then the numbers that went into the religious orders were stunning. Certainly there’s been a lot of scandal and abuse and all sorts of

problems with the system, but there were so many good people in it. I think it’d be a tragedy if they were totally forgotten. Where are we now?

“The diaspora experience that formed in the Famine lasted really from the 1840s until, I think, John F. Kennedy’s election. And then the breakthrough began. The Irish were no longer threatened. Their religion wasn’t threatening anymore.

“So those very strict schools, the solidity of party loyalties weren’t necessary for Irish survival anymore. We’re at the tail end of the post-Famine Irish-American experience. I’m not saying it’s over, but it’s not going to be the same.”

Leave a Reply