“I lost three of my four children. My son is the only thing I have left,” says a mother, her voice choking with emotion.

“In Nigeria, it was all gangs, armed robbers, hired assassins. You were either in or out,” remembers a young man who escaped the violence.

“There was no peace in the Congo. You never knew what would happen. You’d hear bullets – grr, grr – during the night,” says a journalist who fled the conflict.

“The traffickers realized the boy had chicken pox. They didn’t want the rest of us catching it so they threw the boy overboard. Nobody opened their mouths about it,” says a man who is still too frightened to reveal his identity.

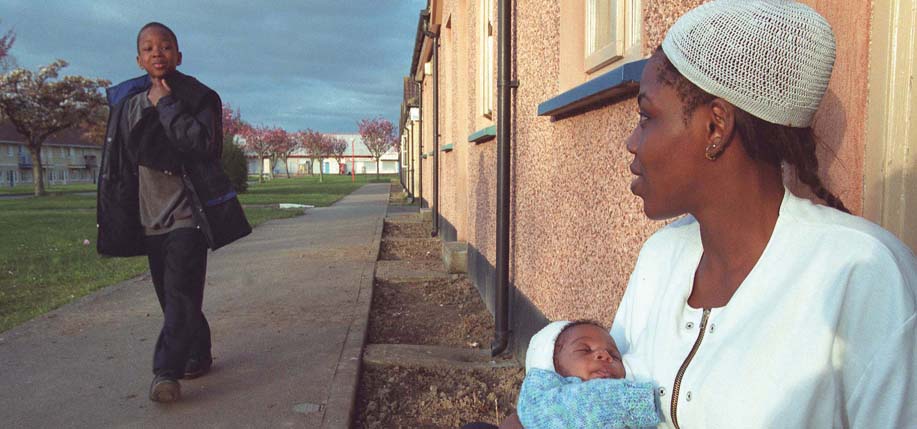

These are the real-life stories of some of the most marginalized people in modern-day Irish society – people who have come to seek asylum.

Nigerians, Somalis, Romanians, Afghans and Sudanese for the most part, these people have been arriving in Ireland in their thousands every year. In 2006 – the latest year for which figures are available – 4,314 people sought asylum in Ireland, down from a high of 11,634 in 2002.

Of the many that arrive, only approximately one in ten are granted the legal right to remain. Who are these people? And what are their lives like?

Seaview, a new documentary by two filmmakers from Dublin, aims to answer these questions.

“Asylum seekers are rarely given an opportunity to speak,” says Nicky Gogan, who collaborated with Paul Rowley in making the film. “This film is a chance for their voices to be heard.”

Seaview is the story of one particular group of asylum seekers, those who currently reside or have resided in Mosney; a one-time holiday camp for Irish families located about 25 miles north of Dublin.

Founded in the 1940s as part of the Butlin’s chain of holiday camps, Mosney was once a place of refuge for Irish families. At its height, it catered for up to 6,000 holidaymakers every day.

The Mosney of today is still a place of sanctuary but in an entirely different way. Its residents are asylum seekers, 800 of whom are housed here at any one time.

These asylum seekers live surrounded by reminders of Mosney’s past. Curtains in bright 1970s patterns, a neon sign advertising “traditional fish and chips,” the ballroom with its parquet floor—all played host to generations of Irish holidaymakers.

Paul Rowley, Nicky’s partner in making Seaview, was struck by these visual contradictions. “It’s an isolated holiday village which is completely kitted out for entertainment,” he explains. “And now it’s being used as a place where people wait in hope and fear for years on end.”

The film highlights these contradictions. Images traditionally associated with recreation and enjoyment, such as the gaily decorated swimming pool, are represented while the residents tell their often traumatizing stories.

These are stories that might never have been told were it not for Paul and Nicky’s decision to deviate from their original plan for a fictional feature film.

Both visual artists and friends from when they met in San Francisco in 1994, the pair had long wanted to work together. Distance (Nicky moved back to Dublin in 1995 and Paul moved to New York) prevented them from doing so.

It wasn’t until the advent of modern communications and cheap flights that they were able to undertake their joint project. In 2004, they started work on a feature film focusing on newcomers to Ireland.

“At the time, the government was talking about housing asylum seekers on ‘floatels,’” recalls Nicky. “These were to be virtual prisons out at sea. We were shocked they could think of treating people like that. After all, we’re a nation of migrants. The Irish have been refugees all over the world.”

Indeed, she and Paul have both been migrant workers themselves, having worked in London, Germany and the U.S.

Having decided on a theme that interested them, they started their research by visiting Mosney, one of the biggest residential units for asylum seekers in Ireland.

“Almost as soon as we got there, we realized the real story was far better than fiction,” says Nicky. “Telling it would be more interesting and more valuable to the asylum seekers themselves.”

One of the reasons for this is that the ‘real story’ differs quite substantially from the common public perception of asylum seekers in Ireland.

Because they are not allowed to work while their asylum application is being processed, asylum seekers are provided with food, accommodation and a weekly 19 euros allowance from the state. Some Irish people resent this because they see it as living at the taxpayer’s expense.

Seaview challenges this misconception. “If people knew what these people are going through, there wouldn’t be the same sense of animosity towards them,” says Nicky. “Instead of seeing them as statistics, people would see them as humans who need help.”

It’s this human element that is captured in Seaview. One woman says at the very beginning of the film: “Imagine leaving everything you know as a human being – your home, your memories, your family, your childhood – to come to a country as a total stranger and to start all over again.”

Viewers don’t have to imagine as the asylum seekers interviewed for this film tell us exactly what this feels like.

The young man who fled the violent streets of Nigeria couldn’t believe his eyes when he traveled by train to Mosney.

“Seeing cows, the countryside, small houses, I thought,‘Oh man! What’s this?’” he now recounts in a strong Dublin accent.

He’s one of the lucky ones. His application was accepted and he now lives in Dublin City where he makes his living as a musician.

He is grateful for the opportunities Ireland has given him. “It’s a lucky thing I’m here today,” he says earnestly. “It’s a blessing.”

The young mother from Nigeria, who is still waiting for a decision on her case, has not had such a positive experience.

“In Nigeria, the only Irish people you met were missionaries,” she says. “We thought of the Irish as gods. So, when we arrived here and the Irish called us names – liars and thieves . . .” She breaks off crying.

The journalist from the Congo knew a lot about Ireland before he arrived. “The fight for independence, Michael Collins, your long history; it made Ireland feel like a natural destination for me,” he says.

Unfortunately, this did not mean it was a welcoming one. He is still awaiting an answer to his application for asylum and is disillusioned with the system.

“The process is a shame,” he says. “What do the interviewers know about us? What do they know about our countries?”

This is a recurring theme in the film. The asylum process is notoriously slow, sometimes taking up to six years.

During this time, people are not allowed to work. They are not allowed to cook. Their basic needs are looked after by the state and they themselves begin to stagnate.

“The system is inefficient and inhuman,” says Paul. “I’m not talking about Mosney. The staff and facilities at Mosney are very good and the residents are well taken care of. However, staying for such a long time – three, four, five or six years – in a camp for asylum seekers has a huge impact. No matter how luxurious your surroundings, being held in a state of limbo and constant fear for your future has detrimental effects.”

Paul and Nicky met writers, doctors, engineers, lawyers, farmers and artists in Mosney, none of whom were allowed to work. “They lose their skills and their confidence and they remain isolated from Irish society,” says Paul. “It’s a very difficult life to have to live.”

The asylum seekers themselves testify to this. There’s the teenager who, over the course of eight years, saw all of his friends move out of the camp. Some were deported; others were granted leave to remain.

“I smile on the outside but on the inside it’s hard,” he says. “I’m still a refugee in Mosney. Even when I see some of them at school, I can’t talk to them. They’ve moved on and I don’t know what they’re talking about.”

A Kurdish man can’t understand the rule which prevents him from working. “We don’t want anything from the government,” he insists. “We don’t need a house. We don’t need 19 euros. We don’t need a health service. If we work, we can pay everything from our own pockets.”

Having spent four years getting to know these people, Paul and Nicky understand this feeling. “It’s unnatural for them not to work,” says Nicky. “In their countries, if they don’t work, they don’t eat. They work to live.”

She is scathing of the public’s perception of asylum seekers living in luxury at the expense of the state. “They get 19 euros a week,” she says. “They can buy some credit for their phones and make a call home. That’s about it.”

Many of the adults in the film are depressed. Their lives are on permanent pause, indefinitely suspended. “It’s tough for them,” says Nicky. “They are alienated on so many different levels.”

Their children, however, are a source of hope. They attend school and are much more accepting of their situation. “I like reading and spelling,” says one. “I like Ireland because you can do whatever you want,” says another.

However, some of the parents fear for the future. “Children see their parents here, sitting down for years on end,” says a worried mother. “They go for years without eating a meal their mother has cooked for them. What kind of mothering will that mother do when she leaves?”

It’s a question one of the former residents has had to ask herself. After three years in Mosney, Vida, who is from Ghana, had her application accepted. She still laughs at the memory of receiving the news. However, venturing out into the wider world wasn’t as easy as expected. Having lived in Mosney for so long, she had become virtually institutionalized.

“It’s a big difference,” she says. “You are not spoon fed anymore. My son and I almost ended up homeless and we often had no food to eat.”

Now that she has a job, that struggle is behind her. She feels settled. “I feel part of Ireland now,” she says. “I’m glad I’ve been able to make it.”

However, she acknowledges the impact the process had on her. “Everybody who goes through it, their mental condition deteriorates,” she says.

And what for? Only one in ten asylum seekers can expect to start a new life in Ireland. The others are sent back home. In light of such discouraging statistics, it’s no wonder so many asylum seekers suffer psychologically.

As Nicky says, “This film is really about waiting, people going through a long, arduous process of waiting and in the meantime, they are in no man’s land, in limbo.” Life for them is literally on hold.

Both Paul and Nicky hope that their film will have an impact on people and perhaps change some attitudes – both in official circles and among the public at large.

“The asylum seekers themselves told us that,” says Nicky. “They knew that participating wasn’t going to help their cases but it might help people coming after them.”

In order to maximize its chances of doing so, Paul and Nicky are keen to get Seaview widely distributed. It’s been shown at film festivals in Ireland and Berlin. It was in competition at Toronto’s Hot Docs. It’s currently on theatrical release in Germany. Paul and Nicky are both hopeful that it will be shown on Irish national television.

“It’s important that people see it,” says Paul. “We want as many people as possible to see it.”

For Paul and Nicky, life is moving on. They are planning a new film – a fictional story based on what Nicky describes as “colonialism and post colonialism and how Ireland is impacting on the world following its economic success.”

But she is finding it hard to leave Seaview behind. Especially as she knows that so many people are still stranded in Mosney and in other camps all over Ireland.

As the film ends, the scene fades on a long corridor with a locked door in the distance. Such is life for asylum seekers in Ireland today – a long and uncertain wait that may well meet with refusal at the end.

Leave a Reply