September, 1930. Age 16, my mother, Kathleen Sloyan, the second of eight children, leaves her home in Ballyhaunis, County Mayo. She will marry, raise three children, and die in Brooklyn, New York, at age 53, without ever returning home. We have no photos of her as a child.

With my first wage as a paper boy, I bought her a 78rpm record that had “Mayo” in the title. Her hug was a full world. Her eyes filled, and for years I bought her anything that had Mayo in the title. I still love the sound of the word Mayo.

March, 1924. Age 20, my father, Patrick Joseph Murphy, the fifth of thirteen children, leaves his home in Cloone, County Leitrim. He will return forty-five years later, a year after the death of my mother, many years after the deaths of his own mother and father.

We have no photos of him as a child.

This is the story of his journey home. I went with him and met myself.

In the Brooklyn world of my childhood, Ireland was always there on my mental horizon – in the rhythms of speech and turns of phrase of Irish people about the house; in the ballads about the old country and a moonlight in Mayo that could bring my mother to tears; in the Friday night card games in which a priest visiting from Ireland might occasionally loosen his collar and mutter a sort of curse when the Lord failed to fill his inside straight.

Ours was a world of aunts, uncles, cousins; the calendar had its comforting rhythm of gatherings for holidays, baptisms, communions, graduations.

And, the funerals. Always uncles, John, Michael, Frank, each death strange in its own way, each one driving my father deeper into himself.

I was eight when Uncle John fell over the banister on his way up to his apartment, dropped three stories, and broke his neck. I didn’t really know him, but I can still see him falling.

Then, I was nine when Uncle Michael fell under the wheels of the IRT subway, the family said it was the heart that gave way, dead before he hit the tracks, others whispered that he had jumped.

My Dad said his brothers had bad luck. Mikey must have had the old heart attack. John, another story, let him be, no point in going on about it, let it be, drop it.

Then, my godfather, Uncle Frank the bachelor, a large man with gruff manners whose hand swallowed mine when he shook it, his breath spoke of cigarettes, whiskey, and anger. I felt bonded to him as my godfather and a bit afraid of him at the same time.

He drank himself to death. I was thirteen when he died, my father was fifty and was burying his third brother in America. Years later, I would begin to understand his loss and the pain that he kept inside as the funerals kept coming. But then, I was young and my father’s losses were distant. I went to my uncles’ wakes and funerals and then came home, tired after a day of play with all the cousins.

I remember a deeper sense of loss about Uncle Frank’s death than about John or Michael. Perhaps because I was older, the idea of death had begun to have meaning, but I also think that, despite my youth, I sensed Uncle Frank was a lonely and unhappy man, moving in a world too far removed from our Christmas dinners for me to understand. He remains very much with me since he is in my parents’ wedding picture, the best man. The picture is on a table in our bedroom, so I see it at some level of my consciousness every day.

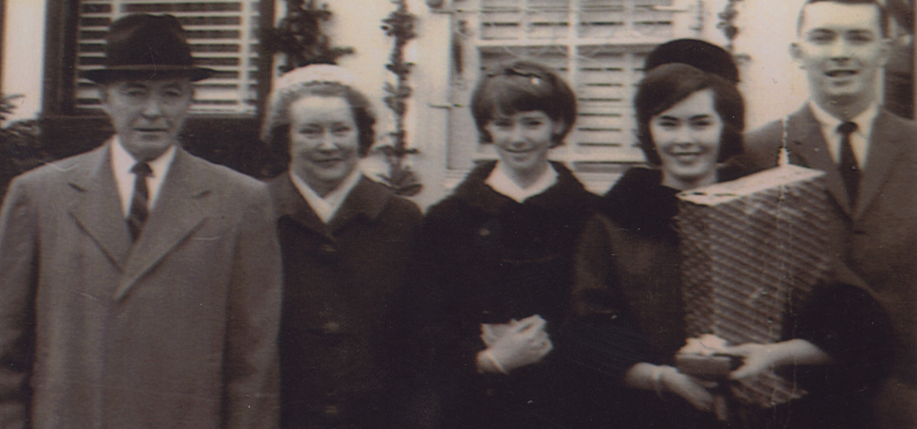

A lovely picture, taken in New York in a studio, light years way from Leitrim and Mayo. The whole picture speaks of Ireland, of emigration, and of change, especially the poses of the four men – my Dad, Uncle Frank, Mark Cummings, and John Foley, my Dad’s best friend and himself off the boat like the rest of them. There they are in their rented tuxedos, probably for the first time in their lives, looking stiff, awkward, proud of themselves.

Immigrants to a new world, just starting out, so far from their homes. Why this formal studio photo session? I now realize that it was to send their word home that all was well, that they were prospering in the new world. The photo sent home says, “Not to worry, all’s well.”

In Aughakiltubred, parish of Cloone, County Leitrim, what could my grandparents, John Murphy and Bridget Maguire, possibly have thought when this picture arrived in the mail? There they are – two of their sons, Patrick and Francis, long gone from home and not likely to return; dressed in tuxedos for a marriage, one of their sons marrying a woman they would never meet, a formal occasion at which parents should be honored and basking in the glow of the moment, but there are no parents in these wedding photos. These parents are an ocean away from this wedding and will not be seen again by their children, and will know many of their grandchildren only in the stream of photographs that will try to shrink the distance.

I now know that such photos were regularly sent home to Ireland from the States – a steady chronicle of marriages and births. How many of these photos came in the mail over the years? And then, the stream of photos of grandchildren, an expanding family in America and Canada known to them only in these photos. Hard to imagine their sense of separation.

The distance between these two worlds of our family came to me one day when I came home from school and my Dad was there, home earlier from work than was normal. My intuition said that something wasn’t quite right. News from Ireland – my grandmother had died. Naive, I don’t think I had ever thought of my parents having parents. I really couldn’t grasp the whole idea of it – my father had a mother but she lived far away in this mysterious place we talked and sang about. I had a grandmother, she had died, my Dad would never see her again.

He sits there, silence fills the room, and I try to understand this mystery.

My Dad went home for the first and only time in 1969. My Mom had died the year before, and my sisters and I were especially aware that she had never managed a trip back home, so we gave the trip home as a Christmas present. Since he wouldn’t risk such a journey on his own, I was more than willing to be his partner. A very exciting prospect for me, a chance to close the distance between the Ireland of my imagination and the reality.

But, while I was excited, I can’t say that Daddy, as we called him, was at first thrilled at the prospect. I think, in fact, that he may have been a bit intimidated by the whole idea. Since he hadn’t been a letter writer, the links to Ireland had been maintained more by and between our aunts who passed the news on to us. After the deaths of his brothers, all his links to Ireland had closed down. Aunt Catherine called it a hopeless place. Aunt Rose had gone home once, come back, and said it was beyond hopeless.

My Dad was a warm, loving man, full of sharp humor, always humming tunes he composed as he went along, but at the same time he was a man of few words, at least in terms of his personal feelings and experiences. I suspect that is, at least in part, an Irish trait, especially on the male side of the fence, but planning this trip energized him in a special way. He began to speak more about Ireland as the trip approached, he had lots of questions. He wanted to look good, so off we went to Sears and Roebuck on Bedford Avenue, our idea of high fashion. He was clearly nervous about the whole thing.

I don’t think I fully understood his emotions at the time. Ours was to be a five-week trip, visiting Ireland and England. In each place, he had both his own and my mother’s family to visit. Only as we talked on the plane did I realize that much of his nervousness came from worry that he might not like all these people. There he would be, for five long weeks, “at home,” but in a world of strangers. So again, the distance that was so much a part of the lives of all the Murphys in America came to the fore, now a very real emotional reality. What would he have to say to his brother Eddie and to his sister Ellen? After all, they wouldn’t be interested in baseball, one of his passions that was a sure indicator he had become a Yank. Would he like the world of in-laws he was about to meet for the first time?

As it turned out, there was no need to worry. Ireland fit him like a glove. He settled immediately into its rhythm, his brogue increasing ever so slightly.

After a few days visiting with my mother’s brothers and sisters in Mayo, it was off to Leitrim, the real goal of the whole trip. As we neared his home turf, he began to recognize landmarks, houses, churches. Now we didn’t need the maps I had been studying so carefully since Shannon Airport. He became the guide.

We were closing distances.

“Turn here,” “Make the next right,” “If you turn here, you’ll see Reynolds’ place,” “The next house should be John Lee’s,” etc. Much had surely changed in forty years, but he knew this place; its houses and turns of the road had histories that he was remembering; this world of rough, marginal farmland, clearly not prosperous, was the place of their beginnings – all the Murphy boys and girls who wound up in Brooklyn, Manhattan, Canada, Rhode Island, California, England, in jobs and worlds far removed from their parents who worked this stubborn Leitrim land to feed them.

When we came to the turn for Aughkiltubred, Daddy said we should keep going a bit further, make a few turns. He said there would be a place a bit up the road where we could buy some beer and stout to take up with us. Partly, he was testing his memory; partly, he was stalling.

His memory was good. There was indeed a place that was not really a pub in today’s terms; rather, it was a sort of general store that also served as the post office and pub. Brady’s, rough cement floor, and a few make-shift seats.

Only a few people in the place, and they watch us like hawks as soon as we come in. Daddy doesn’t introduce himself, there is a deep quiet, we order two pints, tourists passing through.

I still feel his tension. He has gotten the place right in his memory; he has found it after all those years, but will this place know him? Then, some small talk about the weather — “grand day,” “lovely,” “oh, it was bad this day a week.”

We order twelve bottles to go, itself an insurance policy against disappointment.

And then a moment that closes all distances.

One of the men looks up and says, “Is it Packy Murphy?” There he is, Patrick Joseph Murphy, looking all too American in his Sears and Roebuck best, but he is surely close to home.

“Packy?”

No hesitation, “John Francis?”

Obviously, Daddy had recognized John Francis Mulvey or at least suspected that he did. No dramatic hugs — a quiet handshake, and Mulvey, “We knew you were coming home. Eddie’s expecting you above.”

A remembered conversation, hopefully close.

Perhaps this moment is more in my own memory than in reality. Nonetheless, I remember it as a great release for Daddy. If he was okay with John Francis, surely he would be okay with his brother and sister. A few pints and some memory-lifted laughter helped to loosen his mood. Then, off up the hill to home.

When Uncle Eddie came out to greet us, I realized that this was surely an uncle. He and Daddy were so clearly brothers, their features so similar that they were as one, much more so than I remember any similarities between Uncle Frank and Daddy. Even before any words were said, their facial resemblance alone shocked me into memories of long dead uncles in America.

Great distances were closed in that meeting of two brothers who hadn’t seen each other in forty years. Their greeting itself was not dramatic in any gesture or outward emotional demonstration. Brothers in more than looks, they deflected emotions, keeping their inner worlds to themselves. For all anyone could tell, they might have seen each other last week.

A handshake, no hugs. “You’re welcome home . . . a fine day . . . Here, sit by the fire . . .” Whiskey all around — the only public acknowledgment of a special occasion.

I count myself lucky to have been with my Dad when he finally went home. Little did I know on that special day, but in two years he would be dead. Eddie is now gone as well.

I like to remember the two of them, slowly and a bit awkwardly coming to know each other again. Aunt Maggie giving us a bit of tea, Daddy gradually settling into a rhythm of memory and laughter as old friends came by and nostalgia filled this small, warm, secure place. He was home, a circle had been closed.

He had lived his life far removed from this starting place, and now he was back — forty years after his starting out on the road to America. He had married and buried a wife, seen his three children grow up and do well in a world of baseball and rock ‘n’ roll; he had coaxed whatever he could out of a backyard Brooklyn garden, and he saw himself as quite the barbecue chef; he had labored on a bread van, tried his hand as a union organizer and, once, he had received a safe driver award that we all knew must have been a mistake.

That was his world as I thought I knew it.

But, as the days passed in Ireland, listening to him talk and remember with his friends, hearing the laughter about some forgotten wildness when they were all young bucks, watching him walk the fields with his brother, seeing the easy way he had with cattle, I realized that I had always known instinctively about this other world. Without my realizing it, Ireland had been one of my parents’ gifts to me; perhaps without their even intending it as a gift, but here it was.

A white-washed cottage in Leitrim, no running water, three rooms, a central fire — in this place, my Dad and the aunts and uncles of my growing up were all born.

All along on that trip, I had thought I was taking my Dad home. Now, I know he was showing me my own starting place. He took me home.

What a wonderful, tender and heartfelt memory. It awakened thoughts of my own Da, brought up on a farm in Derry and living in urban Glasgow and taking any opportunity to ‘work the land’ albeit a small plot, may they all R I P they are home now