My friend Michael says he has a charming mother. He hastens to add: “I know you think we all do, but my mother has charms other than the ones on her gold bracelet. She has the ability to stop bleeding and cure burns and headaches and sprains and styes in the eyes just by laying on her gentle hands and reciting words handed down through the centuries.”

The concept doesn’t surprise me at all. Folk remedies are not exclusive to the Irish. When I was a child and came down with a fever or sore throat my Italian grandmother used to place her hand lightly on my forehead and murmur a string of singsong syllables. Almost immediately my temperature would drop and my discomfort would diminish.

Neither my mother nor her siblings knew how their mother achieved her cures, replying when questioned only, “It’s a secret.” Since my grandmother didn’t speak English and none of her grandchildren were taught Italian, I couldn’t ask her to teach me her folk remedy, but I listened carefully and memorized the sounds. Years later when my own daughter experienced an occasional fever, I mimicked Nana’s ritual and found it to be as effective as ever, even though to this day I have no idea what I was saying.

Michael is more fortunate than I. His mother Patricia, born and bred in Belfast, still has the yellowed slip of paper inscribed with words that were passed on to her more than fifty years ago. Her charms can only be revealed to a family member of the opposite sex, but she did share how it was that she came to learn them. While watching a boxing match on television with her father-in-law, who was a devoted fisticuffs fan, his sparring favorite received a blow that bled profusely. When the elder gent whispered a few words and the bleeding stopped, his son chuckled, “Ah, Da’s charmed another one.”

Stopping bleeding, a most useful charm, is mentioned in the Tain Bo Cuilange, or Cattle Raid of Cooley, when Cúchulainn and Ferdia are so badly wounded that they are beyond the help of herbs and plants and “nothing could be done but lay magic amulets on them and say spells and incantations to stop the spurts and spouts of blood.” After the boxing match ended, with an eye to safeguarding his future grandchildren from cuts and other potential maladies, Patricia’s father-in-law wrote down his charms, cautioning her to mind the confidentiality caveats or their potency would be lost forever. His admonition to secrecy reeks of Irish faerie lore.

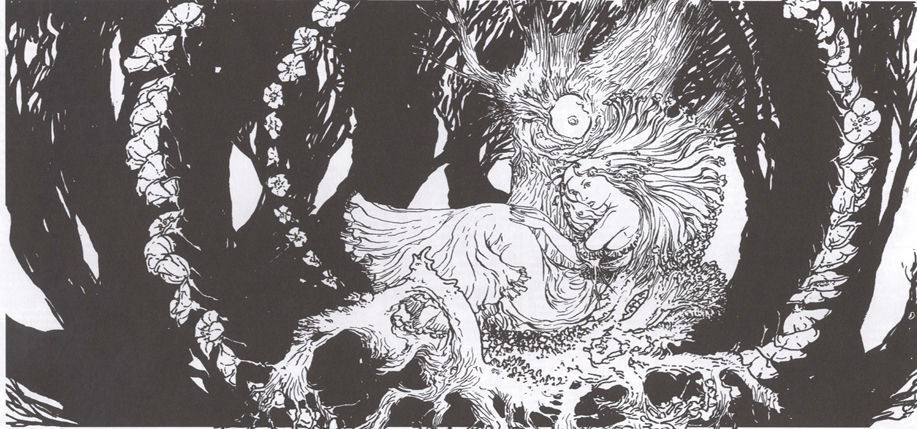

Illnesses and injuries were thought to result if one of the faerie folk was treated with unkindness or disrespect, or if their activities were disturbed in any way, such as building a house atop one of their favorite pathways. Conversely, it was also believed that physicians and healers received their curative skills directly from the faeries. A tale told around the hearth fire speaks of three women from Dingle who needed to cross a river and encountered a beautiful lady on its bank. When she asked for their assistance in fording the water, two of the women said they were already carrying too heavy a burden but the third generously put aside her own parcels and carried the lady to the opposite side. On reaching dry land, the stranger told her: “When you wake tomorrow morning you will know fully every plant and herb that grows in Ireland.” Next morning on awakening the woman knew all plants and herbs by name, where they grew, and the power of each, and from that moment she was a great doctor.

Admittedly, belief in the faerie folk was stronger before computer technology and workstations in space, but it lingers even now – especially midway between the vernal equinox and summer solstice at the full moon known for millennia as Bealtaine.

Like its autumnal counterpart Samhain (Halloween), Bealtaine, which means ‘bright fire’ and is now celebrated as May Day, marks a time when folk believe the veil between worlds is the thinnest and fairies roam at large. Formerly fields, herds and people were blessed in fire rituals that they might be free from disease, be fertile and produce abundantly through the agricultural season. Though the practice of walking through flames or over glowing embers has all but vanished, certain Bealtaine customs remain.

It is, for instance, the night of nights to pass on family charms, for the charms shared then will be more effective than any told on other days of the year. Herbs cut on that day will hold their curative powers longer and stronger. Washing with dew gathered before Bealtaine dawn will insure that beauty’s rose will fade more slowly. And it is the best time to draw water from a Holy Well to use for healing purposes throughout the year.

Like most other celebrations, Bealtaine has certain traditional foods. Cattle being the significator of Celtic wealth and spring being the time when calves are born, May is the time when cows produce a copious amount of milk. Ireland’s ‘white foods’ therefore are one of the headliners on the May Day menu.

At the top of the milk products list is butter. Until fairly recently every farmhouse churned its own, and since butter was both beloved and nutritionally necessary, superstitions surrounded it. Every good butter-maker had an arsenal of prayers and charms to prevent mischievous or malevolent sprites from jinxing the process. Second only to butter, cheeses of all types, plain and flavored with herbs or honey, also occupied a place of prominence on the Bealtaine table.

Spring’s newly sprouted herbs and flowers are important Bealtaine elements as well. In the mythological tale Cath Maige Tuired, wounded Tuatha De Danaan are healed by being immersed in the Well of Slaine into which had been placed “every herb that grew in Ireland.” All healers, then and now, prize their apothecaries of herbal remedies. Some faerie herbs that were widely used for healing include dandelion (heart disease), eyebright (eye infections), vervain and rowan (general health and prosperity), elder twigs (pain), calendula (fever), and St. John’s Wort (dementia and depression).

Last, but certainly not least, are eggs, with their yolks symbolizing the life-giving sun and the miracle of stones seeming to crack open of their own volition to reveal newborn chicks. With spring’s warmer temperatures, birds once again begin to lay eggs so regularly that there is no want of them for the Bealtaine meal, a fact best expressed by the Celtic proverb “The cocks crow, but the hens deliver the goods.”

While numerous feasts and celebrations pepper the Irish year, Bealtaine is one of the most cherished, and the charm for the time rings with promise of plenty. May the blessed sunlight shine on you and warm your heart till it glows like a great peat fire. Sláinte!

Herbed Butter

2 sticks unsalted butter, softened to

room temperature

4-6 tablespoons minced fresh herbs or edible flowers

juice and grated zest of 1 lemon

salt and pepper to taste

Cream the butter until light and fluffy. Stir in remaining ingredients. Spoon butter mixture onto a sheet of waxed paper and roll into a log approximately 1-inch in diameter. Chill until firm. Slice into rounds for serving. For meats, fowl and fish: any combination of garlic, parsley, chives, tarragon, thyme or basil. For toasted bread: omit lemon, salt and pepper and use 1-2 tablespoons honey plus minced rose petals or lavender buds, minced orange zest and cinnamon, or a combination of cinnamon and nutmeg to taste. NOTE: Never use herbs or flowers that have been exposed to insecticides!

Fresh Farm Cheese

1⁄2 gallon whole milk

1 quart half & half cream

1⁄4 cup lemon juice

Combine the milk and half & half cream in a large stainless steel or enamel soup pot and heat almost to boiling until tiny bubbles appear around the edges. Stir in lemon juice until the milk mixture separates into curds and whey. Remove from heat and pour through a sieve lined with a double thickness of cheesecloth that’s placed over a large bowl. Tie up the curds filled cheesecloth into a ball and suspend over the bowl for approximately 30 minutes or until it stops dripping. Unmold the cheese onto a low-sided bowl and refrigerate until ready to serve. Chilled whey is a refreshing drink.

NOTE: To make an herbed cheese, mix 4-6 tablespoons of minced chives and/or fresh herbs to the curds after they have been unmolded from the cheesecloth, then reform and refrigerate. To make a sweet cheese, substitute 2-3 tablespoons of honey for the herbs; serve plain or sprinkled with finely chopped toasted unsalted nuts.

Baked Milk Custard

2 cups whole milk

1⁄4 cup sugar

1⁄8 teaspoon salt

3 eggs, well beaten

1⁄2 teaspoon vanilla

grated nutmeg

Heat oven to 300F. Blend the ingredients together, then pour into individual custard cups and dust with nutmeg. Place the molds in a pan of water that reaches halfway up the sides of the cups. Bake 45-60 minutes or until a knife inserted into the custard can be removed clean. Chill. Serve plain or with sliced fruit. Makes 4 servings.

Recipes by Edythe Preet

Leave a Reply