Irish Century Series

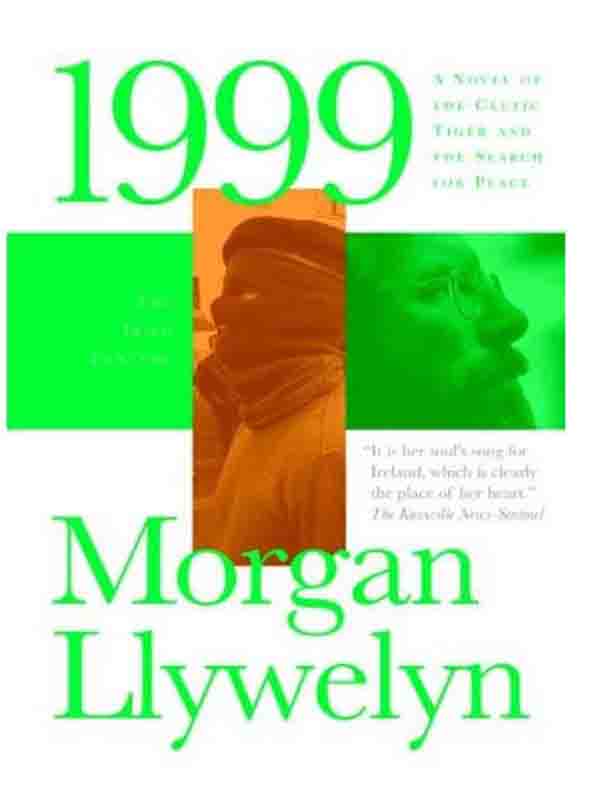

One of the most ambitious projects in recent Irish fiction will be completed when Morgan Llywelyn’s 1999: A Novel of the Celtic Tiger and the Search for Peace is published in February.

($24.95 / 400 pages / Forge).

This is the fifth and final entry in Llywelyn’s Irish Century series, in which the prolific author traces the history of 20th-century Ireland through a single family. Llywelyn’s feat is a remarkable one, which will help countless readers come to terms with the complexities of the Irish century, from the Easter Rising right up to the new millennium.

You’ll just need a little bit of time to take it all in. Llywelyn’s five books weigh in at a total of over 2,500 pages. Llywelyn’s accomplishment is all the more impressive because she continues to publish other books in a variety of genres. Perhaps most famously, her book Grania was the source material for the Broadway musical The Pirate Queen. But the Irish Century series is Llywelyn’s most impressive creation. It is true that these books represent a relatively traditional example of historical fiction. Don’t come to 1999 – or the earlier books, 1916, 1921, 1949 or 1972 – looking for postmodern historical fiction in the vein of Roddy Doyle’s Star Called Henry. Llywelyn dramatizes the well-known events of Irish history through real life figures as well as her own sharply drawn fictional characters. She even provides footnotes and capsule biographies so that readers know a little bit about each character. 1999 revolves around Barry Halloran, a crippled photographer and former IRA member who was in Derry during Bloody Sunday in 1972. By the 1990s, Barry, like so many on the island of Ireland, has renounced violence.

As she has in the series’ four previous novels, Llywelyn spirals back in time, covering the fallout from Bloody Sunday, the Troubles through the 1980s and, finally, the peace process and rise of the Celtic Tiger.

Particularly striking in 1999 is Llywelyn’s handling of the Hunger Strikes, which made Bobby Sands an international icon. Ironically, Llywelyn’s series actually began in 1999 with the publication of 1916. Llywelyn’s main character is Barry’s grandfather, Ned Halloran. Ned’s own parents died on the Titanic. Aimless, Halloran finds a purpose in life when he attends an Irish school with a poet and headmaster by the name of Padraic Pearse. Ned comes of age as a man as well as an Irish patriot, to the point where he is willing to collaborate with those plotting a rebellion in Dublin. Ned’s love life, and life as a soldier, culminate on Easter Monday, 1916.

Next came Llywelyn’s 1921, which catches up with Ned Halloran after the Rising. He has married Sile, but she has caught they eye of Ned’s best friend, a journalist named Henry Mooney. Henry is a study in political and personal moderation. He supports Republican aims but not in extreme forms. Similarly, he does not want to hurt Ned but he can’t deny his feelings for Sile. One of Llywelyn’s great strengths throughout this series is her ability to balance the love affairs of her fictional characters with the broader events of history. Henry eventually finds a beautiful woman of his own, but she is a Protestant, further complicating his feelings about Ireland, religion and revolution, as the creation of the Irish Free State and the Irish Civil War loom.

Ned Halloran’s daughter Ursula is a key player in Llywelyn’s third book, 1949. The focus here is post Civil War Ireland, which has achieved a level of independence, yet seems to have done very little with this newfound freedom.

Ursula works in the fledgling medium of radio, before moving to the League of Nations prior to the outbreak of World War II (during which Ireland was controversially neutral).

Overall, Ursula is a symbol of the kind of woman 1940s Ireland has trouble fulfilling. When she becomes pregnant without a husband, she must flee the very nation her father helped create. Ultimately, Ursula must choose between two lovers, and, in a sense, choose if she wants to remain in Ireland.

The somewhat sedate air of 1949 is cast aside in Llywelyn’s fourth book, 1972, which explores the events surrounding Bloody Sunday and the reemergence of the Troubles in Northern Ireland.

Llywelyn’s main character this time around is Ursula’s son, Ned’s grandson, Barry Halloran, who joins the IRA in an effort to liberate what he sees as Ireland’s last slice of colonized land, the six counties of the North.

Aside from the political turmoil, once again there is romantic entanglement. Barry falls in with a volatile Irish American singer, before ending up in Derry on that fateful Sunday in 1972.

Finally, of course, we learn what comes of Barry, his lover, and Ireland as a whole in 1999. Llywelyn’s Irish series is far from perfect. It is very long and her prose can seem quite breathless at times. There is also a Forrest Gump-ish quality to some of the cameos of historical figures. But make no mistake about it, Llywelyn’s books stand as one of the more important works of recent Irish fiction.

Fiction

Frank Delaney had a best seller a few years back with the not-so-creatively entitled Ireland. Now he’s back with another blandly named but engrossing read, Tipperary. Delaney explores the life of a 19th-century memoirist named Charles O’Brien who may (or may not) have rubbed elbows with the likes of Oscar Wilde, James Joyce and Charles Stewart Parnell.

Just as interesting is the time O’Brien spends with more common folk as he wanders the countryside, claiming he has healing powers and listening to the locals, who were brimming with rage and revolutionary energy.

At the age of 40, O’Brien also falls for an eighteen-year-old British girl. All of this is told by a present-day narrator, who we eventually learn has as much at stake in this story as O’Brien does.

“Be careful about me. Be careful about my country and my people and how we tell our history. We Irish prefer embroideries to plain cloth,” O’Brien says at one point, later adding, “To us Irish…memory is a canvas—stretched, primed, and ready for painting on.” Tipperary is an impressive work of art indeed.

($26.95 / 464 pages / Random House)

Dubliner Niall Williams burst upon the literary scene with Four Letters of Love, and followed with As It Is in Heaven, The Fall of Light, and Only Say the Word.

All were epic in nature, dealing with families, God and other powers beyond our control. Williams has now written a fictional life of John the Apostle. Entitled John, the novel explores the final years of John’s life, which were spent on an island in exile. This is a departure from Williams’ earlier works, but not as much as it might seem. In the end, John the Apostle must hold on tight to his faith in the face of many conflicts, from his failing body to rebels within his own group of disciples. Williams’ work has always been about themes such as endurance in the face of adversity.

($24.95 / 256 pages / Bloomsbury)

Peter Tremayne’s latest ancient Ireland mystery (following Master of Souls) starring Sister Fidelma is entitled A Prayer for the Damned. This time around, Sister Fidelma is about to get married, much to the chagrin of those who feel celibacy is the only acceptable state for a woman of God. In fact, it may have been one of Fidelma’s opponents who murdered a wedding guest, leading to the postponement of the marriage ceremony, and putting Tremayne’s endearing protagonist on yet another case.

Needless to say, though Tremayne’s eye for historical detail remains sharp, A Prayer for the Damned also touches upon many contemporary issues, including celibacy, gender and church leadership. Tremayne (the pseudonym for scholar Peter Berresford Ellis) has produced another winner.

($24.95 / 320 pages / St. Martin’s Minotaur)

Patrick Taylor gained prominence with An Irish Country Doctor, and he returns to a colorful Northern Ireland locale for his latest An Irish Country Village. In this novel, a doctor named Barry works for the famously quirky Dr. Fingal O’Reilly. Despite some of the difficulties, Barry feels right at home in Ballybucklebo – that is, until the sudden death of a patient sullies Barry’s reputation.

Once again, Taylor masterfully charts the small victories and defeats of Irish village life. He is also the latest author (see the latest books by Maeve Binchy and Tana French) to explore modernization and its ill effects on Ireland, by way of the proposed destruction of Ballybucklebo’s beloved Black Swan pub.

($25.95 / 432 pages / Tor-Forge)

NonFiction

5For the Republican perspective on the recent historical events in Northern Ireland, pick up An Irish Eye, the latest chronicle of current events and behind-the-scenes politicking from Sinn Féin leader Gerry Adams.

In 2005, the IRA ended its armed campaign and, two years later, threw its support behind a new policing system for Ulster. Adams has been a major player in these events which, a decade earlier, would have seemed unthinkable. Adams also weighs in on conflicts which endure across the globe. He tells this story with clarity, and with much more sly wit than one normally expects from politicians.

($22.95 / 320 pages /Brandon-Dufour)

In fact, for some perspective about just how bad the North was not so long ago, flip through the pages of Hunger Strike: Reflections on the 1981 Hunger Strike, featuring a wide range of writing from the likes of Edna O’Brien, Christy Moore, Tom Hayden, Ken Loach and over two dozen other contributors

($23.95 / 267 pages / Brandon-Dufour)

Dan Barry has worn numerous hats at The New York Times. Until late in 2006, he wrote the About New York column, bringing the heart, soul and eye of a poet to some of the city’s grittiest corners. It was a bit odd, then, to see Barry take on the new challenge of a weekend column called This Land, which sends him out to a very different landscape – the 50 U.S. states. Barry responded gamely, filing brilliant columns about farmers and addicts, police officers and criminals. Still, for those who miss Barry’s New York stuff, a new book called City Lights collects his columns on street peddlers, Buddhist monks, the bygone Fulton Fish Market, McSorley’s Old Ale House and the Plaza Hotel. Barry’s 9/11 columns, meanwhile, serve as an alternative, small scale history of those dark days.

($25.95 / 320 pages / St. Martins)

Leave a Reply