Bill Flynn’s commitment to the community is rooted in his Irish Catholic childhood.

℘℘℘

“No pessimist ever set foot on Ellis Island, no pessimist ever crossed the prairies, and no pessimist ever built cities from one end of the continent to another. These things were done by people with vision and hope.”

Thus does Bill Flynn wonderfully describe the country he grew up in and the people who made it what it is. Flynn himself embodies that vision. He is a chronic optimist, even when it comes to the most intractable problems. He says it springs from his father and mother, who, despite raising a family through the Depression, never lost their hopes and dreams for their young family and their ambitions to do better every day of their lives.

The Irish poet Eavan Boland wonderfully summarizes what the generations of immigrants went through in order to give their kids the opportunity of America. Bill Flynn can relate to it in the stories of his parents.

“What they survived we could not even live.

By their lights now it is time to imagine how they stood there,

what they stood with,

that their possessions may become our power:

Cardboard. Iron.

Their hardships parceled in them.

Patience. Fortitude. Long-suffering

in the bruise-coloured dusk of the New World.

And all the old songs.

And nothing to lose.”

While Bill was growing up, the topic of Ireland often got debated across the kitchen table in the Flynn household. Though he describes his father as mild-mannered, other relatives who came over from Northern Ireland were not as forgiving of the harsh world from which Catholics had come. Essentially corralled into a state they felt no allegiance to and had never voted to join, they were strangers in their own land, second-class citizens and heavily discriminated against.

Flynn remembers some firsthand experiences. “We had relatives that would come in. They would tell the most awful stories. They were intensely interrogated by us as kids, but it led my own general disposition to question the British, and to be aware of the problems faced by Catholics in the North, to hate bigotry, and to hate sectarianism, really. Later on, those meetings had their impact, and suddenly I began to read about and study what was going on. There were other Irish influences, a lot of music, reels, dancing. Dad was, I think, more romantic about Ireland than was Mom. I think the women had it much harder. Peggy’s mother felt that way too.

“My father went back only once. He stayed with his only surviving sister, Rosena. As it turned out, he almost died over there. Struck with pneumonia, he came back early. For years he wanted to make the journey once again, but there was never really the opportunity for him financially or otherwise.”

Bill Flynn made his first trip back to Ireland in 1971. “I took my mother over to visit her old home in Co. Mayo and to visit with my father’s only surviving sister, Rosena, in County Down, Northern Ireland,” he remembers. It was to be his introduction to the North. It also spurred renewed interest in his roots.

“It’s a mysterious force, it’s like gravity; you can’t see it, but you can feel the pull of it. It’s a feeling of being home and being at one with people—a coming together.”

But it was other world trouble spots that interested him at first. One of his favorite comments is that if you believe in something, “sending a check is not enough. If you believe in something, you simply have to support it in every way.”

Bill Flynn believed he could make a difference. Despite leading a major insurance firm that was experiencing rapid growth and consumed all his working hours, Bill Flynn was curious about giving back, about getting involved in issues greater than himself.

His deep religious faith also spurred him. Unusual for a corporate chief executive, he combined a significant spirituality with a can-do business attitude. He appointed several Jewish leaders to his board and became very friendly with Elie Wiesel, the Nobel Peace Prize winner, writer and Holocaust survivor.

“Elie is a great teacher; he helps you understand the darkness in the soul of men, but also the greatness that can reside there, as it surely does in him. There are some men who have earned the right to preach, to tell the world what they must do. Even if he had never won the Nobel Prize, Elie is one of those men.”

Flynn became a board member of the Elie Wiesel Foundation for Humanity after Wiesel won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1986. In 1990 Mutual sponsored the “Anatomy of Hate” conferences in Paris, in Oslo, and later, other major cities around the world, hosted by Wiesel’s organization. At these meetings, world leaders, including many Nobel Prize winners, gathered to examine the lethal effects of hatred on people and society with a view to discussing how to get beyond hatred. Flynn was deeply impacted by the clear efforts to bring about peace in conflicts such as the Middle East and South Africa. Inevitably his thoughts turned to his father’s native land. Two years earlier, Mutual had sponsored the Williamsburgh Charter, which addressed the issue of religious liberty in a pluralistic society. Clearly Northern Ireland was a case study for such an issue. In 1992, Flynn took the plunge into his own ethnic history urged on by a Sister of Mercy, Sr. Carol Rittner. He sponsored a Beyond Hatred Conference in Derry, Northern Ireland entitled “Living with Our Deepest Differences”, meeting for the first time with Sinn Fein, SDLP and Unionist leaders of Northern Ireland.

“I was learning, like everyone else who approached this issue. I hope I was humble enough to listen and, I hope, hopeful enough to not let the negativity that was still widespread put me off trying to help.”

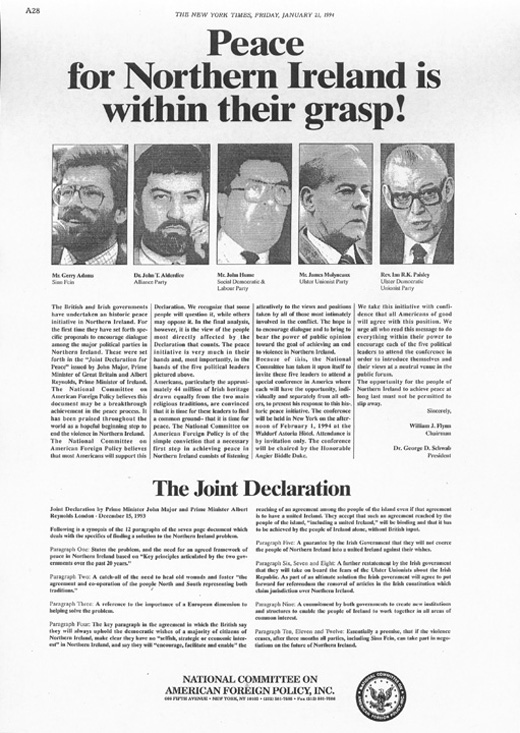

The sprigs of peace were beginning to sprout in the North at that stage. Revelations about SDLP leader John Hume and Sinn Féin leader Gerry Adams meeting with Rev. Alex Reid in secret at Clonard Monastery in West Belfast to hammer out a common attempt at a way forward were raising hopes for the first time in decades. A new Taoiseach (prime minister) in Ireland, Albert Reynolds, was making renewed efforts to crack the twenty-five-year deadlock. Flynn was suddenly hopeful. Since 1987 he had been seeking a way to become involved. Back then he had joined the Irish American Partnership and led an American delegation to Ireland to meet with Paddy Harte, the Donegal member of Parliament who saw the partnership as a powerful vehicle to involve America. The effort petered out, however, and Flynn’s next attempt had been with Nobel Peace Prize Winner Mairead Corrigan and her American coordinator, Sister Dorothy Ann Kelly, president of the College of New Rochelle.

Flynn remembers that early involvement. “Dorothy Ann was head of the Peace People in the States, and she was deeply into this fine organization. I used to go to all their meetings and contribute to it as well. Mairead Corrigan was a powerful speaker. She’d get your blood going about what was going on in the North, so I became a real fan. I said to Dorothy Ann, I wish I knew more about all this. And she said, “How would you like to learn more about the Peace People?” And I said I would, and she said, “I’ll take you to Ireland and I’ll introduce you to all these people.”

“We had a great week meeting all the Protestants and Catholics alike. It was a great learning experience. It also helped me to decide the level at which I wanted to operate.”

Flynn also had contact with Irish Northern Aid, the Republican fundraising group in America. He particularly remembers a conversation with two leading Noraid members in his Fifth Avenue office. Flynn was troubled by the high level of violence in the North and, to a degree, by Noraid’s efforts in support of Sinn Fein. He explained to them he could not support those using force to accomplish their purpose in the North. Then the men asked him what he was prepared to do or was he just content to blame others from the sidelines. “They made me feel like a draft dodger,” said Flynn.

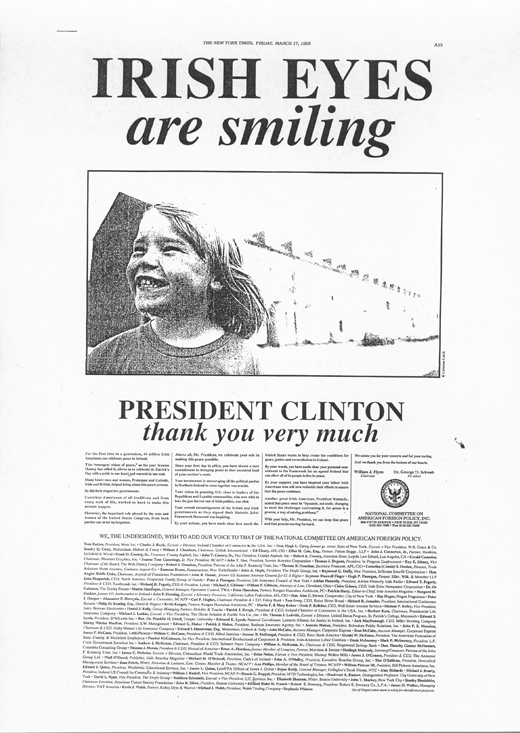

His chance to play a major role came soon after. A small group of Irish Americans in New York was in close contact with the Clinton presidential campaign and had received assurances from them that Clinton would address the issue of Northern Ireland once he was in office. It was the kind of breakthrough that Irish America had always dreamed of: an American president becoming involved in the search for peace in Northern Ireland.

It was a time and a tide. Positive conflict-resolution efforts were taking place in the Middle East and South Africa, the Cold War was over, and the ties between Britain and the United States were not as critical as they once were. The end of the century was coming up, and a generation of Northern Ireland leaders were suddenly asking, why not us? Many of them saw America as the key.

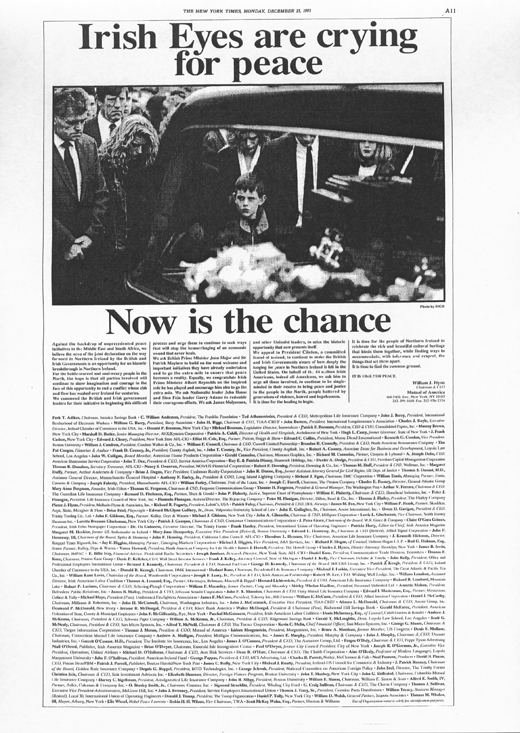

The Irish-American group needed key names in the community to join them. Bill Flynn was already a standout, both in pursuing conflict resolution and as a successful and respected businessman, but would the Mutual of America chief risk his public profile, his business success and his Chairmanship of the National Committee on American Foreign Policy, in seeking to help bring what many believed to be an unsolvable conflict to an end?

Flynn never hesitated when he was asked. In the citation for his selection as one of the 100 Irish Americans of the Century, Irish America stated that “William J. Flynn will always be remembered as the man who dispensed with a great taboo—the notion that American business should not get involved in bringing peace to Ireland. He broke the mold when he set out in tandem with a few others to change the reality that American business had nothing to offer toward peace in Ireland. The historic peace process was the result.”

Bill Clinton was elected in January 1992. By September that year, the Irish-American group, numbering just five people including Bill Flynn, former Congressman Bruce Morrison, businessman Chuck Feeney, and labor leader Joe Jameson, were ready to play their part. The endgame was set to begin. ♦

Leave a Reply