Back in July, Bronx Irish Catholic Edwin F. O’Brien, after a 40-year career as a priest, military chaplain and aide to two cardinals, was named the new Archbishop of Baltimore.

The archdiocese O’Brien will lead numbers more than a half-million Catholics, with 200 priests, five Catholic hospitals, two seminaries and 151 parishes, including two cathedrals, The Baltimore Sun noted.

O’Brien said he will focus on getting to know the priests of his new archdiocese, which covers nine Maryland counties and the city of Baltimore.

As O’Brien becomes more familiar with his new home, he will inevitably make one important discovery. Though it is rarely mentioned in the same breath as New York, Boston or Chicago, Baltimore is historically one of the most important Irish-American cities in the U.S.

To begin with, Baltimore is named after a village in Ireland. It is also the oldest Catholic archdiocese in America, and was long seen as a place of refuge for Irish immigrants who felt the sting of discrimination.

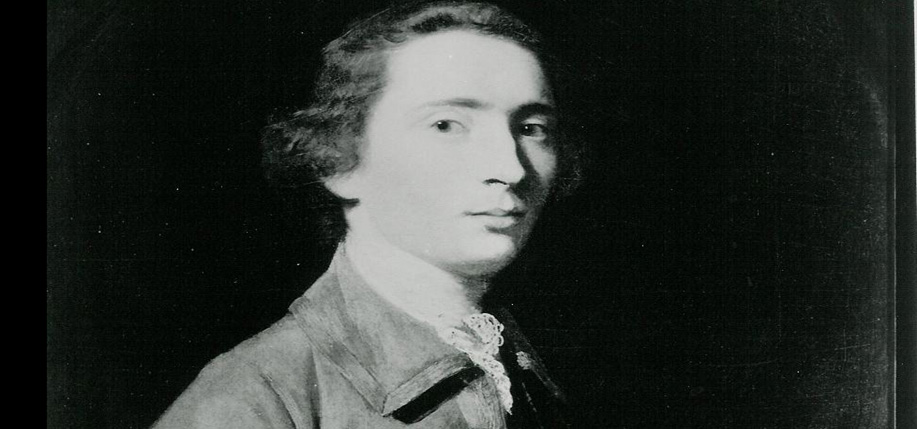

Most importantly, Baltimore has long been associated with America’s first great Irish-American family. Long before the Kennedys built their powerful dynasty from the slums of Boston, the Carrolls of Maryland amassed great influence inside the church and in society at large. By 1776, when America’s Declaration of Independence was announced, just one Catholic signed the famous document: Charles Carroll. When the Archdiocese of Baltimore was established in 1789, it was another member of the sprawling family, John Carroll, who was selected to lead it as Archbishop.

This year marks the 300th anniversary of the birth of Daniel Carroll, a land baron whose holdings stretched into what is today’s Washington, D.C.

These days, with a spiritual leader named O’Brien and an ex-mayor (now Maryland governor) named O’Malley, Baltimore retains its heavily Irish flavor. Thousands descended upon Canton Waterfront Park on September 14 and 15 for the annual Baltimore Irish festival which celebrated Irish music and culture.

But it is in Baltimore’s past that a fascinating, often forgotten slice of Irish-American history resides. Some people have argued that you can use the Kennedy family to understand the history of the Irish in post-Famine America.

It is not an exaggeration to say that you can look at the Carrolls and their experiences in Baltimore to understand Irish Catholic history in America prior to the Famine.

So who were the Carrolls? Where in Ireland did they come from? Why did they settle in Maryland? And why was Baltimore so important to Irish Catholics in general?

Roots in Cork

Baltimore, Maryland was established as a city in 1729, and (according to The Encyclopedia of the Irish in America) was named after a port town in West Cork. The name Baltimore is derived from the Gaelic baile an tigh mór, meaning “the village near the big house.” By that time the Carrolls had already established themselves as an influential family with extensive landholdings in the Maryland area.

In Ireland, the Carrolls had dominated a region encompassing parts of Counties Laois, Offaly and Tipperary, Timothy J. Meagher writes in The Columbia Guide to Irish American History.

The Carrolls, however, paid dearly for their devout Catholicism in Ireland and the U.S.

“The Carrolls’ position as Catholic outsiders in Protestant Maryland and their conscious memory of their family’s long, bitter, and ultimately futile struggle against conquest and dispossession in Ireland provide more than a different perspective on early American society,” Ronald Hoffman writes in his 2001 study Princes of Ireland, Planters of Maryland: A Carroll Saga, 1500-1782.

“Threatened relentlessly between 1500 and 1782, first by the territorial ambitions of rival clans, then because of their stubborn attachment to their Gaelic heritage, and finally for their defiant adherence to Catholicism — both in Ireland and in Maryland — the Carrolls consistently developed strategies comparable to those used by their ancestors, confronting each peril with compromise, cunning, implacable will, and a tenacious determination to survive.”

Driven from Ireland by conflict with English Protestants, Charles Carroll left Litterluna, in present-day Offaly, and settled in the American colonies.

A Safe Haven

Why did Charles select what today is the state of Maryland?

Maryland had a long tradition of religious tolerance, which was forged by the Catholic Calvert family. It was Sir George Calvert who, in 1635, had successfully petitioned King Charles I to establish a colony called the Province of Maryland where Catholics could live freely.

Throughout the 17th century, as Protestants and Catholics across the British Empire battled for supremacy, Maryland and its fledgling port city of Baltimore was seen as a relatively safe haven for Catholics in the American colonies.

As it turned out, Charles Carroll (known as “The Settler”) picked a bad time to come to Maryland. Initially, he was named the colony’s attorney general (serving under the third Lord Baltimore). However, England’s so-called Glorious Revolution of 1688 ushered in yet another era of Catholic subservience and Protestant ascendancy, which made its way to the colonies as well.

Still, though Catholics were disenfranchised, the Baltimore region remained a relatively good place for Irish Catholics, as evidenced by the landholdings and fortunes established by Charles Carroll and his two sons Charles (born in 1702) and Daniel (born 300 years ago, in 1707).

Indeed, despite the swirling religious acrimony of the era, which pit Catholics against Protestants, Baltimore’s diverse blend of Irish and English Catholics, not to mention Irish and English (and Scottish) Protestants, suggests that some people did manage to get along and establish a certain level of peace in the New World.

Along with the tradition of religious tolerance established by Cecil Calvert (Sir George’s son), Baltimore’s geographical location, a substantial distance from the Northeast and bordering on the American South, presumably helped the city avoid some of the problems of New England, where a more rigid form of puritanism held sway.

After all, 1688, the year Charles the Settler came to the U.S., was the same year a devout Catholic and Gaelic-speaking Irish woman named Goody Glover was hanged as a witch in Boston.

Baltimore’s Irish Foundation

Well into the 1700s, Catholics were forbidden to attain a good education or hold public office.

Still, having attracted prominent families such as the Carrolls (who were educated in Europe), as well as Irish Catholic immigrants of more modest means, Baltimore was transforming into a bustling city by the middle of the 18th century.

St. Peter’s on Charles Street was built in 1770 and became the city’s central Catholic church. Around the same time, future Archbishop John Carroll and his brother Daniel built a chapel in Rock Creek, Maryland to serve Catholics in the area.

It is important to note that Irish Protestants also flocked to Baltimore. Many of the most prominent Irish in early Baltimore were Presbyterian, The Encyclopedia of the Irish in America notes. In 1761 nine or ten Scots-Irish families formed Baltimore’s First Presbyterian Church. Baltimore’s first mayor, the Irish-born John Calhoun, emerged from this church.

By the 1770s, when American independence from Britain dominated public debate, the Carrolls entered the fray. They, along with many other Irish Catholics, argued that freedom from Britain and its Old-World religious conflicts would actually encourage greater religious tolerance in the New World.

“America may come to exhibit a proof to the world, by general and equal toleration, by giving a free circulation to fair argument, is the most effectual method to bring all denominations of Christians to a unity of faith,” John Carroll wrote in his much-discussed book An Address to the Roman Catholics of the United States of America. (John was motivated to write the book not by some anti-Irish nativism but by another relative named Charles, who had left the church and become anti-Catholic.)

John and yet another cousin named Charles (this one was the Settler’s grandson, born in 1737) played central diplomatic roles in the buildup to the U.S. war for independence. Both accompanied Benjamin Franklin on an official visit to Canada in 1776.

Charles risked his life and fortune by signing the Declaration of Independence, the only Catholic to do so.

America’s First Catholic Diocese

By 1789, John Carroll was the logical choice to lead Baltimore’s growing Catholic community.

Carroll, who served as Archbishop until his death in 1815, gave future American Catholic leaders a blueprint when it came to establishing a Catholic diocese. A fierce proponent of education, he pushed for the creation of what would later become Georgetown University. In 1809, he also encouraged Elizabeth Seton to establish the American Sisters of Charity for the education of girls.

Charles Carroll, meanwhile, was elected to serve in the U.S. Senate as well as the Maryland state senate.

The Carrolls, however, were just the most prominent of many Irish contributors to the area.

County Down native Robert Garrett came to Baltimore in 1801, and would preside over a family that played key roles in the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O).

The Hibernian Society of Baltimore was founded in 1803. The group’s president was John Campbell, a veteran of the 1798 uprising in Ireland.

Nativist Action

All in all, the first several decades of the 1800s seemed to bear out Cecil Calvert’s vision of religious tolerance from nearly two centuries earlier. Of course, things were not so simple. In the 1830s, there were bursts of anti-Irish and anti-Catholic prejudice in Baltimore, as there were across the country. One particularly ugly episode was the so-called Carmelite Riots of 1839, when a great mob attacked the Carmelite convent for three days. These followed a familiar pattern of anti-Catholic violence in America, when Protestants came to believe Catholics coerced women into becoming nuns.

The infamous Know Nothing movement of the 1850s also hit home in Baltimore.

Worse, a distant member of the Carroll clan, Anna Ella Carroll (who had left the Catholic church), publicly supported the Know Nothings.

But the Irish kept coming, especially once the Famine struck. In the 1850s and 1860s, before the American Civil War, nearly 70,000 new Catholics entered Baltimore, the majority of whom were Irish.

The B&O railroad was a steady source of employment for the Baltimore Irish. Not surprisingly, Charles Carroll was a key investor in the venture.

Honoring the Irish

Five years ago, Baltimore’s Irish Shrine and Railroad Workers Museum at Lemmon Street opened. The site honors the laborers who flocked to southwest Baltimore in the 1840s. Around this time, a new St. Peter’s Church was also built to serve the rapidly growing Irish Catholic population in the city’s western neighborhoods. A young Irish priest named Edward McColgan led the flock.

The Sisters of Mercy (originally formed in Dublin) also established numerous local missions and schools to teach and tend to the needs of these newly arrived Irish.

Church, labor, education – as in many other big U.S. cities, this was the Baltimore Irish recipe for advancement.

One of the most important advocates for Irish Catholic education throughout the mid-19th century was Emily Harper MacTavish, who donated land and funds to many projects. Then again, MacTavish came from a long line of strivers. Her grandfather was a prominent Baltimore citizen, a senator and signer of the U.S. Declaration of Independence named Charles Carroll. ♦

Thank you……….

I read that the Charles Carroll estate is now on the campus of John Hopkins University.

John Carroll Begley- you are correct. The Homewood Estate (home of Charles Carroll) is the present campus of John Hopkins University.

Thank you My father names is willian kalanta and he change to colan ….?

Great to have all this information of our ancestors. Anyone have info on the Carrolls of Chicago and stockmarkets?