The Billionaire Who Wasn’t by Conor O’Clery tells the story of Chuck Feeney, a young Irish-American who became rich beyond his dreams, only to give it all away through his fund Atlantic Philanthropies. The following excerpt opens just after Feeney graduated from Cornell College in 1965 with a degree in hotel administration.

By mid-summer of 1956, Chuck Feeney still had no idea what to do with his diploma. But after Cornell, he felt confident he could go anywhere in the world. He had a bankroll of $2,000 based on his casino winnings, and he still had four months left of the thirty-six months of government money from his GI scholarship. To claim the remainder, however, he had to enroll in a course, either in the United States or abroad. Many hours spent in the Hotel School library reading books on tourism and travel had stimulated his urge to see the world. He had always wanted to go to Europe, and the bankroll was burning a hole in his pocket. He went to the French Consulate on Fifth Avenue and Seventy-fourth Street in Manhattan to inquire about tuition fees in French colleges. To his surprise, he learned that university education in France was free. That was even better. He bought a cheap ticket for a Cunard liner and within a few weeks, he was in Paris. After signing up for a month’s intensive course in French at the Sorbonne, he wrote off to colleges in Grenoble and Strasbourg asking for admission.

In early September 1956, the secretary in the admissions office of Grenoble University in southeast France looked up to find the twenty-five-year-old crew-cut American in her office. “Here I am, I want to register for the school, for the political science department,” said Feeney in heavily accented French. “The dean sees no one,” she replied stiffly. “Well, I’m here,” he said.

“I kept sitting there reading my magazine and this guy kept shuffling in and out of the room,” recalled Feeney. Finally, in some exasperation, the secretary said, “The dean will see you.” “Naturellement,” replied Feeney. In his office, the dean said, “Monsieur Feeney, you are an interesting candidate.”

“Yes, I appreciate that!” “You see, you are the first person to request admission to the political science school of Strasbourg and send the letter to Grenoble!” Feeney had put his application letters in the wrong envelopes. He shot back. “Yes, but it’s evident I’m here and it’s here I want to be. If I wanted to go to Strasbourg I would not be in Grenoble.” The dean threw up his hands. “Why not!” he said. He admitted Feeney for a master’s course in political science at the fourteenth-century university. The Cornell graduate was the only American in the department, something of which he was always proud.

Life was cheap in Grenoble, spectacularly sited in a broad valley surrounded by the snow-capped French Alps. Feeney’s basic living costs came to about $15 a month. His French, tennis, and skiing improved considerably. The U.S. government inexplicably sent him $110 scholarship checks for six months rather than four. Someone up there likes me, thought Feeney.

At the end of his eight-month course, Feeney hitchhiked south with his kit and tennis racquet, looking for money-making opportunities. Getting rides was difficult as there were so many people on the roads holding up handwritten signs to show their destination. Outside Antibes, he displayed a notice in large letters on his tennis racket saying, “English conversations offered.” He had no trouble getting a lift after that. On the Mediterranean Coast, Feeney met an American who was teaching children of naval officers from the U.S. fleet based at Villefranche-sur-Mer, a picturesque port of eighteenth-century houses and steep cobblestone alleyways. Villefranche was the home port of the USS Salem, a heavy cruiser serving as the flagship of the U.S. Sixth Fleet with a complement of nearly 2,000 officers and enlisted personnel. “I started to realize there were these naval dependents around,” said Feeney. “I asked him [the American teacher] what they did in the summertime and he said they were at a loose end, so I decided to start up a program like a summer camp for the navy kids.” Feeney had seen a business opening and a way of being helpful. He rented a room in a pension in Villefranche and organized a summer camp on the beach. Almost seventy American kids were delivered into his care by grateful Navy parents, and Feeney had to hire four other Americans as staff.

In Villefranche, Feeney made a deal with the tennis club manager to sweep the courts in return for playing for free. On the courts, he met André Morali-Daninos, a French Algerian psychiatrist on vacation who was intrigued by the young, educated American doing a job young French students would disdain. Morali-Daninos was a highly decorated war veteran who had joined the French Resistance during World War II and had brought his family to Paris in 1945. They came to Villefranche for their summer holidays, and in those days before mass tourism, the family usually had the beach to themselves.

Morali-Daninos’s twenty-three-year-old daughter, Danielle, a student at the Sorbonne in Paris, was somewhat disconcerted therefore at the invasion of the beach by dozens of screaming and whistling children with their American counselors. She was particularly struck, however, by the kindness and firmness with which the good-looking group leader treated the children. The vivacious French Algerian and the twenty-six-year-old Irish American got to talking, and a romance started up.

In Villefranche, Feeney came into contact with people making a living from the U.S. Sixth Fleet. Groups of pretty women and salesmen waylaid the sailors and hustled for orders to supply the ship’s exchange store. He got to know a money changer named Sy Podolin who had bought up a row of old lockers and rented them to naval personnel so they could dump their uniforms and change into civvies when on shore leave. For a couple of weeks in August, Feeney made some extra money by managing the “navy locker club” for Podolin in the evenings, opening up the lockers for sailors coming and going to the bars.

As the summer ended, Feeney planned to head north again. He loved the student life and “had enough money squirreled away that I could have gone to a German university.” However, one night in a Villefranche bar he met an Englishman, Bob Edmonds, who was trying to start a business selling duty-free liquor to American sailors at ports around the Mediterranean. He asked Feeney to help him.

The U.S. Navy did not allow the consumption of alcohol on board, but Edmonds had established that sailors could buy up to five bottles of spirits duty free and have them shipped as unaccompanied baggage to their home port. It could be a big market: There were fifty ships in the U.S. Sixth Fleet in the Mediterranean and the crews were rotated three times a year. The savings for the military personnel were huge, and almost every seaman on board could afford to buy a five-pack for collection back in the United States. A five-pack bought duty free in Europe cost $10, including delivery, while the same five bottles in the United States would cost over $30. Edmonds had failed to convince a British military supplier, Saccone & Speed, to work with him and had gone out on his own. He desperately needed an American to help him.

“There’s a big fleet movement, forty ships are coming in,” he told Feeney. “I can only see twenty. I’m looking for a guy that can see the other twenty.” “What do you mean?” asked Feeney. “Go and talk to them about buying booze.”

Feeney and Edmonds started going on board ships to take orders from the crew members, mainly for Canadian Club whiskey and Seagram’s VO. They then arranged for the liquor to be shipped to U.S. ports from warehouses in Antwerp and Rotterdam. There was no need for capital, as they did not have to pay for the merchandise in advance. For a period they had the market to themselves, but competitors were quick to arrive. Edmonds went to check out new opportunities in the Caribbean while Feeney went to Edmonds’ home in Hythe in the south of England to process orders. Feeney returned to Villefranche in October and was told the U.S. Sixth Fleet was heading for Barcelona. He took the train to the Spanish port, only to discover that the ships had been delayed.

Feeney had read in a Cornell alumni bulletin that Robert Warren Miller, another graduate of the Hotel School, had started work at the Ritz Hotel in Barcelona. With time to kill, he made his way to the Ritz on the tree-lined Gran Via de les Cortes Catalanes. Entering the lobby, he saw the familiar figure of Miller, with a shock of brown hair and a cheeky grin, behind the reception desk. They hadn’t been friends at Cornell – Miller was a year ahead of Feeney – but Miller recognized the wiry blue-eyed American immediately.

“Feeney,” he said. “What are you doing here?” Replied Chuck, “What are you doing here?”

That casual exchange marked the start of one of the most profitable partnerships in international business history. ♦

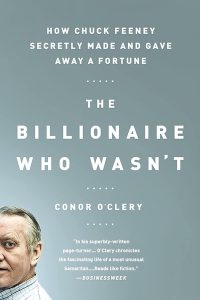

The December/January 2004 issue of Irish America featured Chuck Feeney on the cover with an article by Conor O’Clery “One Life To Give.”

Leave a Reply