Tom Deignan reflects on a time when many of the Boys of Summer had a touch of the Irish brogue.

A recent New York Times article about the consistent success of the Minnesota Twins baseball organization made numerous important points about how teams in smaller cities can compete with financial giants such as the New York Yankees, Boston Red Sox and Los Angeles Dodgers.

But two of the key architects of the Twins organization, General Manager Terry Ryan and former manager Tom Kelly, illustrate an oft-forgotten fact: Irish-Americans continue to play an important role in major league baseball.

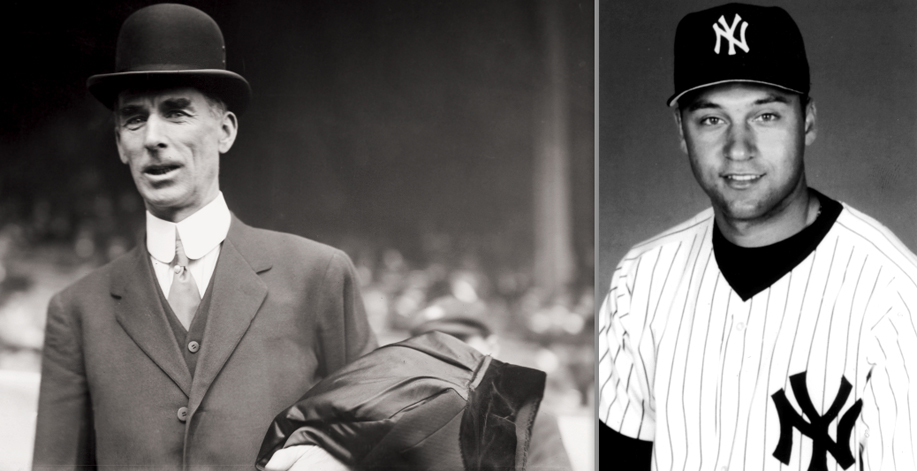

Recent stars such as Sean Casey (first baseman for the Detroit Tigers) and Adam Dunn (left-fielder for the Cincinnati Reds), not to mention the New York Yankees all-star shortstop Derek Jeter (Irish on his mother’s side) indicate that there is no shortage of Irish talent in baseball today.

However, what can’t be denied is that immigrant talent these days comes largely from nations such as the Dominican Republic, Venezuela, Mexico and Japan.

In 2006, according to Stats Inc., nearly 30 percent of major league ball players were born abroad. Dominicans account for roughly 12 percent of current major leaguers.

That, of course, sounds like a recent change in the so-called National Pastime and a reflection of how it has become a globalized sport. However, 100 years earlier, in 1906, Irish-born and second-generation Irish-Americans were the game’s dominant ethnic group, representing as many as one in five ball players. Go back a decade or two earlier and the numbers swell even more.

“Throughout the last two decades of the nineteenth century, more than 40 percent of the professional ball players were of Irish descent,” Irish-American baseball scholar Jerrold Casway notes in his fascinating recent book Ed Delahanty in the Emerald Age of Baseball (Notre Dame University). Right now, the 2007 baseball season is halfway over, meaning it’s time for the All Star game, the midsummer classic. The mid-season break is also a time to take a brief break from the daily grind of the baseball schedule. So, perhaps it’s also a good time to pause and look back at the “Emerald Age of Baseball.”

The Famine and Baseball

Why were the Irish so attracted to baseball? How did they change the game? Who were the top Irish stars of the national pastime?

First and foremost, it must be noted that baseball’s evolution in the U.S. coincided with the spread of the Irish across America, following the horrors of the Famine in the 1840s. Many immigrants and their children had been exposed to the game in big cities by the 1870s, when the baseball league structure we know today was forming. By the 1880s and 1890s, baseball was filled with Irish stars.

“From King Kelly, the flamboyant and self destructive hero of Chicago’s White Stockings and Boston’s Beaneaters in the 1880s, to John McGraw, the hard-bitten, tactical genius of the original Baltimore Orioles in the 1890s and the New York Giants in the 1920s, the Irish certainly seemed prominent wherever baseball was played,” Timothy Meagher writes in the Columbia Guide to Irish American History.

“They included owners, Charles Comiskey of the Chicago White Sox; owner-manager Connie Mack of the Philadelphia Athletics, and managers such as Bill Carrigan of the Red Sox; as well as scores of players and hundreds of thousands of fans.”

Meagher goes on to note that it is no accident that the famous character in the poem “Casey at the Bat” has an Irish name. In an essay published in The New York Irish, Lawrence J. McCaffrey noted that New York teams were particularly Irish during this era. “With Bill McGunnigle as manager and players named Collins, Burns, O’Brien, Corkhill, Daly and Terry, the Brooklyn Dodgers won the National League pennant in 1890. In 1899 and 1900 they again were champions when McGann, Daly, Casey, Keeler (Wee Willie), Kelley, Farrell, Jennings, McGuire, Dunn, Hughes, Kennedy, McJames, and McGinnity played for manager Ned Hanlon.”

Then there were the New York Giants. “In 1904, John J. McGraw managed the National League champion New York Giants. A year later they won the World Series, defeating Connie Mack’s Philadelphia Athletics. McGraw had McGann, Devlin, Donlin, Shannon, Browne, Bresnahan, McCormick, Donlin, and McGinnity in the starting line up. The McGraw-led Giants won National League pennants in 1911, 1912, and 1913, with the assistance of players Doyle, Devlin, Murray, and Burns.” Most scholars agree that aside from the excitement of playing pro ball, many Irish were attracted to the game as a way to escape impoverished Irish enclaves.

Negative Stereotypes

But while this apparent Irish penchant for baseball sped their assimilation, it also fed negative stereotypes. As McCaffrey writes: “Because baseball was the country’s most popular sport, closely linked to the mythical image of a rural Protestant nation, Irish players came to represent American adaptability and their skills in this arena gave them a more acceptable persona than boxing prowess. But athleticism also reinforced nativist opinion that the Irish were strong of back but weak of mind.”

Indeed, in his acclaimed novel The Banished Children of Eve, Peter Quinn has a baseball-loving, anti-Irish character say: “He’s a Paddy, I know, and, it’s not my habit to cheer the likes of ‘em, but there’s no denyin’ the way they take to baseball, like it was in their blood, the same as drinkin’ and thievin’ are.”

In an interview with Irish America, Quinn commented: “I was having a little fun at the nativists’ expense, trying to imagine their response to the fact that this newly born ‘American’ game was so rife with Irishmen. Baseball, of course, was dominated by farm boys and immigrants, ruffians and roustabouts from the urban and agricultural working class, the same as boxing was. In fact, baseball was so physical and rough in those days that it wasn’t far from boxing. As a professional sport, it offered a short cut for outsiders to grab some of the fame and wealth gathered under the rubric of the American Dream — thus the large Irish presence.”

Origins in Hurling?

Cait Murphy is the author of the recent book Crazy ’08: How a Cast of Cranks, Rogues, Boneheads, and Magnates Created the Greatest Year in Baseball History. Among other things, 1908 was the last year the Chicago Cubs won the World Series. Of the era covered in her book, Murphy told Irish America that some of the outstanding Irish players of the day included World Champion Cub Johnny Evers “the heart of the team, of Tinker to Evers to Chance fame. He grew up in Troy, New York, the son of immigrants.” She added: “In the 1900-10 decade, there was still a strong Irish flavor, something like 15-20 percent of the players were Irish, and also a large number of managers.” She then adds: “The Irish presence was actually stronger in the 1890s, an era sometimes referred to as the ‘emerald age’ of baseball.”

It is that phrase that Jerrold Casway, an Irish as well as baseball historian who teaches at Howard Community College, uses in the title of his book. Casway tells the story of Ed Delahanty, the best of six baseball playing brothers from an immigrant Cleveland family. More broadly, Casway explores the heavily Irish flavor of baseball during the late 19th and early 20th century.

“The ‘Emerald Age of Baseball’ and the career of Ed Delahanty were marked by a strong ethnic flavor,” he writes, later adding, “In 1902, an article in the Gael magazine lauded the number of dominant Irish-American baseball players. The author wrote that ‘all outdoor games played with a stick and ball have their origin in the ancient [Irish] game of hurling.’”

Big Changes

Did the Irish change the way baseball is played? It is true they had a reputation for toughness and brought an element of “pep” to the game. “It’s hard to separate the blue from the sky, to know what baseball would have been like without the Irish,” Cait Murphy says.

Casway, however, does convincingly argue that Irish players, with their tradition of union organizing, were instrumental in battling back against greedy owners who raked in money from fans, yet paid players meager wages.

Walter O’Malley, of course, was among the Irish American innovators who made baseball truly America’s pastime by expanding the game to the West Coast.

O’Malley is reviled by those who claim he took the Dodgers out of Brooklyn in 1957. But that tide of opinion is changing. A recent book noted that New York power broker Robert Moses more or less blocked O’Malley’s efforts to keep the Dodgers in Brooklyn, while a June 2007, New York Times article suggests that it was actually the owner of the New York Giants, Horace Stoneham, who was the “real villain of New York baseball.”

These days when you hear the phrase Irish baseball you might be more apt to think about the way the game is expanding in Ireland itself, as noted in the recent documentary The Emerald Diamond. Peter O’Malley Jr. of the L.A. Dodgers has been instrumental in building fields in Ireland, which has attracted second and third-generation Irish-American talent to Irish leagues.

In a sense, this makes perfect sense. One hundred years ago, baseball talent came from Ireland. It is only fitting that the children and grandchildren of those who cheered the likes of Ed Delahanty return the favor. ♦

Leave a Reply