The ad man knew what he was doing. Hired to write copy about a road that didn’t yet exist, he had an idea: create something out of whole cloth. He had as his subject an about-to-be-named Chicago-to-Los Angeles highway, the ramshackle one that would be quilted together from dozens of variously named and sometimes unconnected roads. He would dress that baby up. He’d call it “America’s Main Street.”

Sheer genius, because in one fell swoop, the ad man made an alternate reality for a road that would take ten more years to be completely paved, an alternate reality that Americans bought and have never, as a culture, given up.

For all the things that Route 66 is, it is also a repository of the baggage that one culture can foist upon an inanimate thing. The story of Route 66 is the story of two roads. The first is the asphalt one that existed, the one that brought many Americans west, for whatever reasons, the one that lived and breathed the era it was in.

Then there is the emblematic road, the one we have experienced through an important novel (John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath), a ditty of a song (“Get Your Kicks on Route 66”), a beat poet (Jack Kerouac), a TV show, good press, well-meaning cultural historians and

endless nostalgia.

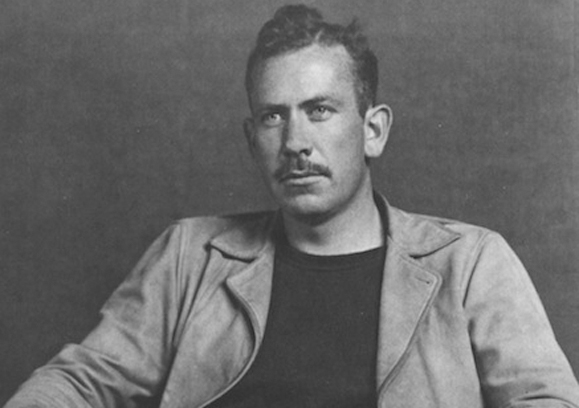

Steinbeck

A California-born novelist who once opined, “I’m half Irish, the rest of my blood being watered down with German and Massachusetts English, but Irish blood doesn’t water down very well; the strain must be very strong,” first referred to Route 66 as “The Mother Road.” John Steinbeck framed the road’s capacity for pathos and redemption; he was also the first to set Route 66 apart as a cultural icon.

John Ernst Steinbeck was born in Salinas, California in 1902. His father, a miller of German extraction, served as Monterey County Treasurer for many years. His Scot-Irish mother, Olive Hamilton, was a schoolteacher who developed in Steinbeck an early love of literature.

In 1919, Steinbeck graduated from Salinas High School as president of his class and entered Stanford University, majoring in English. Stanford did not claim his undivided attention. Steinbeck left the school in 1925 to pursue a writing career in New York City. He was unsuccessful and returned, disappointed, to California the following year.

After moving to the Monterey Peninsula in 1930, Steinbeck and his new wife, Carol Henning, made their home in Pacific Grove. Here, not far from famed Cannery Row, heart of California’s sardine industry, Steinbeck found material he would later use for two of his novels, Tortilla Flat and Cannery Row. Moved to anger by the brutality of the Great Depression, Steinbeck’s characters and stories drew on actual historical conditions and events in the first half of the 20th century.

The Grapes of Wrath

The drought came to western Oklahoma and surrounding states. Then came the wind; before long, the term “Dust Bowl” was coined. Dust covered the crops, choked the livestock, and blew so black that it tricked chickens into roosting at midday. The migrants from whom Steinbeck drew his fiction came out of the South and Great Plains — a great tide of more than a million people that flowed westward through the 1930s in search of work and shelter.

The seeds of the novel were sown some time before the writing of it. One myth has it that Steinbeck joined the migrants on their long trek from Oklahoma City to California. He did not. Returning from a trip to Europe in September 1937, Steinbeck and his wife bought a car in Chicago and headed south to pick up Route 66. He traveled enough of the route to provide geographical details, but his firsthand experience with migrants occurred in the agricultural fields and labor camps of California.

Route 66 is simply a character in The Grapes of Wrath story. It is the journey that imbued the road with its power, not the other way around. And it was the journey that would yield, for Steinbeck, a Pulitzer and later, in 1962, the Nobel Prize for Literature.

The route had a respectable history before it witnessed the flight of the dispossessed. Parts of its northern leg from Chicago to the mouth of the Missouri River followed the 1673 portage route of Marquette and Joliet in their exploration of the upper Mississippi River. In 1926 the road received the official title of U.S. Route 66. It began at the corner of Jackson Boulevard and Michigan Avenue in Chicago and ran 2,248 miles through three time zones and eight states before dead-ending at the corner of Santa Monica Boulevard and Ocean Avenue in Santa Monica. It was called the Main Street of America. Funneled down farm roads of the Dakotas, Nebraska, Kansas, Missouri, Oklahoma, Mississippi, Texas, New Mexico and Arkansas, many refugees could only say that their destination was “West.”

The highway they traveled was Route 66, the road of desperation described by Steinbeck as “the path of a people in flight, refugees from dust and shrinking land, from the Dust Bowl’s slow northward migration, from twisting winds that howl up out of Texas, from floods that bring no richness to the land and steal what little richness there is. People come onto 66 from tributary wagon tracks and rutted country roads. 66 is the mother road, the road of flight.”

Yet, despite the grimness, what many readers of The Grapes of Wrath most remember is its portrayal of the road being a setting for moments of miraculous humanity. Wrote Steinbeck: “There was a family of 12, and they were forced off the land. They had no car. They built a trailer out of junk and loaded it with their possessions. They then pulled it to the side of 66 and waited. Pretty soon, a sedan picked them up. Five of them rode in the sedan and seven on the trailer. They got to California in two jumps. The man who pulled them, fed them. That’s true. But how can such courage be, and such faith in their own species? Very few things would teach such faith.” The road became emblematic of the path to the American Dream, the one that came out of despair.

A Yellow Brick Road to the Emerald City

After World War II, the golden age of the automobile dawned, and Airstream trailers made their way down the route. Merchants and café owners made 66 colorful enough and diverting enough to change the notion that the route was a road to someplace else; rather, it was a destination in itself.

The modern gas station was born here. Phillips 66 gasoline was so dubbed because a company official was testing the gas in a car in Oklahoma. Someone remarked that the car “goes like 60.” The official looked at the speedometer and said: “We’re doing 66.” The car was doing 66 mph on Route 66 near Tulsa. The company took the hint at its next board meeting and the Phillips 66 company was born.

The End

President Dwight Eisenhower, who had seen the efficiency of Germany’s roads during World War II, decided in 1956 that this country needed a quick way to get troops, materiel and people to where they were going. If you were a former general, the destination became the point again. If you were busy, ditto. Passage of the Interstate Highway Act of 1956 sounded the death knell for Route 66, replaced by something called Interstate 40.

The small town of Williams, Arizona tried to say no to the interstate, but in 1985, the last official Route 66 signs came down. That is, federal highway officials said it wasn’t their road anymore and they weren’t going to maintain it. Nevertheless, much of the pavement remains, and a great deal of Route 66 is still navigable, if you can find it.

What to See and Do

The Mother Road lies in scattered fragments, here and there. Sometimes it’s a trendy thoroughfare through urban centers and storefronts appealing to nostalgia:

66 Antique Mall. Salon 66. Saloon 66. Route 66 Roadhouse. In some little towns, it’s an abandoned main street.

Off a dusty farm road near Lamont, California, John Steinbeck found a haven amid fields of toil. The Arvin Federal Camp, or Weedpatch Camp as it was known, still stands on the edge of town. Here, Steinbeck described a place where migrants could find shelter, sanitary facilities and, above all, dignity.

It still offers all that. The camp, now called the Sunset Labor Camp, is home to migrant workers and their families. Most are the children of Mexican immigrants.

If the Mother Road is known historically for anything special besides seemingly endless desert, reptile farms and funky motels, it is food. Not the homogenous fast-food outlets of today, but the individual mom-and-pop restaurants of mid-20th-century highway lore. Many of these special Route 66 eateries — some dating to the 1920s — are alive and well, still serving their specialties, which provide motorists with a taste of local color, life and fare.

Just west of Oklahoma City in downtown El Reno, Robert’s Grill has been serving tasty onion burgers since 1926. There are no booths or tables inside the small white building, only a dozen stools around an L-shaped counter. Even the prices seem from an earlier era: seven hamburgers for $5. In Santa Rosa, New Mexico, the Club Cafe, dating from 1935, has a mini-museum on its walls featuring Route 66 memorabilia.

Many of the visitors at the Route 66 cafes, museums, and roadside cottages are from Western Europe, Japan and Asia. Some Route 66 books are printed only in foreign languages. Web sites are multilingual. There’s even a Route 66 bar in Ireland.

Speaking of which, there is a certain fascination that foreigners, particularly the Irish, have with Route 66. In August of 2006, I encountered a group of Irish bikers in Tulsa. As a news reporter observed, you might have heard the roar of many Harleys, but if you got close, you would have heard Irish accents too.

Some 93 Irish bikers roared into Tulsa, looking for a taste of America. They also had a serious goal: raising money for a children’s hospital in Dublin. The enthusiasts rode through eight states in eight days on old Route 66. And since they raised more than a million dollars, the saddle sores didn’t matter.

The flags were Irish but the bikes were American. The motorcyclists rented their machines in Chicago and dropped them off in Los Angeles. For Jenny Huston, an Irish radio announcer, and Tony Toner, the road captain, the welcome the group received was a little too warm. “We’re melting,” said Toner. “I stood 6 foot 6 when I left Chicago and now I’m 6 foot 2 and shrinking rapidly. We’re not used to this kind of heat in Ireland. But we’re bearing it for a good cause and to find out about the Route 66 most of us have only read about and seen on television. The Irish have always been explorers and adventurers. We love motorcycles back home and it’s easy to understand why Route 66 is considered by many to be the most iconic road on the planet.”

“If I could do this book properly, it would be one of the really fine books and a truly American book,” John Steinbeck wrote in his journal. “But I am assailed by my own ignorance and inability.”

He was 36, an Irish-German Californian, a college dropout who had been a laborer, then a journalist documenting the plight of the migrants. He was also an established author who had written a half-dozen novels, including Of Mice and Men.

When The Grapes of Wrath was published in April 1939, schools and libraries banned it, preachers railed against it and Oklahoma Congressman Lyle Boren denounced it as “a lie, a black, infernal creation of a twisted, distorted mind.”

The book did win Steinbeck worldwide acclaim and spurred congressional investigations into California labor practices. It created a stir that lasted long after the wartime buildup brought migrants jobs and World War II sent those migrants into battle.

Steinbeck wrote a dozen more novels before his death in 1968, but nothing compared with his Dust Bowl epic.

As recently as 1990, a Broadway stage version of The Grapes of Wrath won a Tony for best play.

After completing The Grapes of Wrath, Steinbeck recorded in his journal that he should someday write a book depicting his own people. Fourteen years later, he began Salinas Valley, the story of his mother’s Scot-Irish family, the Hamiltons. After he introduced the fictitious Trasks, whose story consumed the novel, Steinbeck changed the title to East of Eden. The theme inherent in East of Eden was the dream of all settlers in the Salinas Valley, both migrant and native, that there they would realize an earthly paradise.

Somewhere along the way, Route 66 became our collective highway experience. And in the 20th century, we were looking for one. We were about to become a culture that would discover not just the automobile but with it the knowledge that we didn’t have to live forever in the place we started. We could dream. We could expect better.

We were about to take a long road trip. We needed a metaphor for the journey. We got it on Route 66. ♦

Leave a Reply