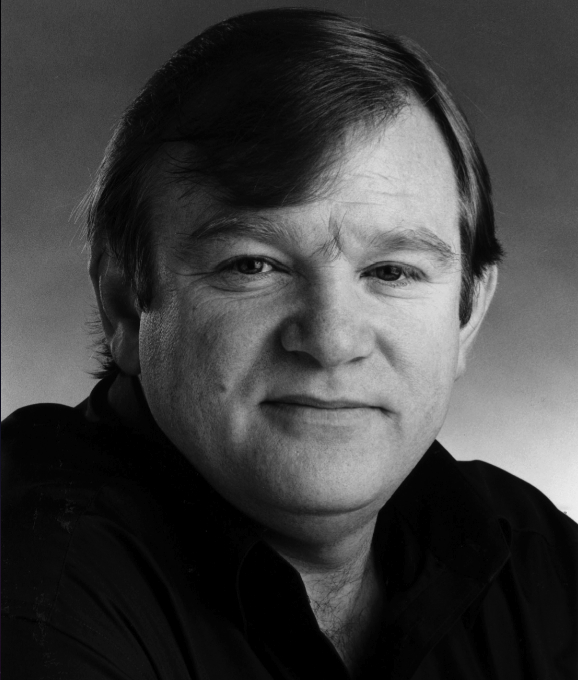

Lauren Byrne talks to Brendan Gleeson, one of Ireland’s most prolific actors, about his varied career.

In real life he’s trimmer than his oversized movie presence, but at over six feet and with his thatch of red hair, several heads turned as actor Brendan Gleeson strolled into the lounge of Jury’s Hotel in Boston, the rain beating against the windows as if to make him feel more at home. The evening before, he’d received an award for his contribution to Irish film and TV at Magner’s Irish Film Festival. “There’s nothing he can’t do,” director Neil Jordan said in a video-taped tribute to him, and even allowing for the hype necessitated by these occasions, few actors can match Gleeson for the variety of roles he’s tackled or for the sheer number of movies he’s appeared in. If there’d been an award for the hardest working actor, he’d have walked away with that too.

For an actor with such a high work profile, Gleeson is curiously absent from magazine covers and celebrity columns. But that’s OK, he prefers it that way. He may have the magnetic appeal of a superstar but at heart he’s a character actor who loves the magic of vanishing into a fresh identity with each new movie.

“It was odd,” he says, reflecting on the award ceremony. “I found myself looking at clips and saying, maybe I could have done it a different way.” Showing none of the violent intensity he can display on screen, his most obvious trait is a gleeful chortle at the memory of some character he’s played or in anticipation of some upcoming project. “I felt lucky to have had a go at these characters in the various movies. Because you do get to like them and know them, and you’re in their corner when you take somebody on. No matter what sort of person it is.”

Even The General, John Boorman’s 1998 biopic about the equal parts charismatic and sadistic criminal Martin Cahill aka the General gave Gleeson his first significant lead role. It also earned him a lot of grief in Ireland, where he was accused of glamorizing crime. Gleeson is honest enough to admit that the license to inhabit the skin of outsiders like Cahill without having to pay the consequences can be fantastically liberating. But he adds, “I spent a long time wondering about this film. Is it to make a hero out of some guy who took people’s knee caps off? I take the responsibility very seriously of not getting off on all that kind of stuff. But I’m convinced that there is redemption in everybody. In the promotion we did for the movie, John and I discussed the notion of inhuman behavior. That’s not the way to describe the behavior of Cahill. It’s actually quintessentially human because we keep doing it – every generation, every class of people, it’s part of us. So the sooner we stop thinking of ‘us’ and ‘them,’ the more chance we have of dealing with whatever is going on.”

Earlier this year Gleeson’s opinion on another topic of Irish life also caused a stir. In an interview on Irish TV’s long- running Late, Late Show, Gleeson, who, unlike many of his Irish acting contemporaries, lives in Ireland year-round, blasted the country’s inadequate national health system, and castigated its managers, saying “a baboon could sort it out.” Fast on the heels of the interview came the release of The Tiger’s Tail, John Boorman’s movie exploring the dark underbelly of Ireland’s newfound wealth. Gleeson plays dual roles as a less than ethical businessman riding the boom and his homeless brother. English-born John Boorman who has lived in Ireland for over 35 years has been accused of sour grapes and the movie has been panned by many.

“John is a great man for pushing things into uncomfortable areas,” Gleeson says. “He just doesn’t accept that you have to stay quiet. We’re lucky to have someone with that degree of intimacy and detachment. We Irish feel, as long as you get the nod and the wink you’ll be looked after, but actually, we’re being exploited by our own people; by people in positions of power. We can’t blame the Brits anymore. ‘You’re saying negative things about the country,’ people have said, which is the most ludicrous notion. It’s not a Bord Fáilte ad; it’s supposed to be an examination of aspects of our society. As artists that’s our job.”

Gleeson takes his role as an artist seriously. As he told his audience at the award ceremony, the desire to “impart some truth” has dictated his acting choices. It’s a subject he returns to again. “There was a time when a father would have his son as an apprentice or a mother would teach her daughter the ways of the world. That’s largely lost now, but movies show us what life is like. As actors we are telling people they are not alone.”

Born in 1955 in Artane, a working-class suburb on the north side of Dublin, at a young age Gleeson discovered the thrill of losing himself in an acting role. He also became an accomplished fiddler, and after college did a stint busking in Germany before returning to Dublin to take up teaching. In his spare time he continued to act for local theatre companies such as Passion Machine, founded in 1984 to stage original Irish work and for which Gleeson wrote a number of plays. In 1990 he made his film debut in Jim Sheridan’s The Field, and followed up with minor roles in Far and Away and Into the West and TV parts, notably his portrayal of Michael Collins, a role he lost to Liam Neeson in the 1996 movie about the revolutionary hero. At age 34 he had enough acting work to give up teaching but hesitated, fearing that the pressure to earn a living from acting would ruin it for him.

His big screen breakthrough came in 1995 with Mel Gibson’s Braveheart. Since then he’s racked up an impressive list of credits, with starring roles in such movies as Mission: Impossible II, Steven Spielberg’s Artificial Intelligence, Martin Scorsese’s Gangs of New York, and lead roles in several movies, including Brad Gann’s Black Irish, shot in Boston, and Paul Mercier’s Irish production Studs, two of Gleeson’s recent outings shown at the festival alongside the Oscar-winning short movie Six-Shooter by playwright Martin McDonagh.

Warnings of the “dog eat dog” world of professional acting was another reason Gleeson hesitated before taking up acting full time. The truth, he insists, is “not half as bad as people imagine.

“What you get are clashes of sensibilities. People going in two directions, and that’s when it gets difficult, because it’s a clash of instincts. Sometimes good things come out of it. I’m a great man to argue, but I don’t believe in out and out war. Some people get off on that. I much prefer where there’s some kind of shared sensibility.”

In some of his most recent movies the name Gleeson has appeared more than once in the credits. If that didn’t hint at some family involvement, the flame-red hair of these younger Gleesons certainly would. With no encouragement from him, two of Gleeson’s four sons are now in the business. “It’s something I avoided as long as they were kids because I think this industry can pull kids out of shape if you’re not careful. But they’re men now so they can decide for themselves.” Older son Domhnall started out with a view to being on the other side of the camera, but landed a role in the most recent production of Martin McDonagh’s The Lieutenant of Inishmore in London’s West End, which later repeated its success in New York. He also has a small role in McDonagh’s short movie Six-Shooter. Younger son Brian plays the son to Gleeson’s businessman character in The Tiger’s Tail. “I knew from an early age that he had that ability to totally immerse himself in playing a character,” says Gleeson. “We’ll see,” he adds, sounding for a moment like any dad predictably worried about his children’s future.

Having starred in the last Harry Potter movies, Gleeson will be showing up again as Professor MadEye Moody in the forthcoming Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix. He’ll also be seen in Beowulf with Angelina Jolie and Anthony Hopkins. Meanwhile he’s writing a screenplay for Flann O’Brien’s At Swim-Two-Birds, an ambitious project for which he’s hoping to round up all the high-profile Irish actors on the international scene. And in April, alongside Colin Farrell, he starts shooting Martin McDonagh’s first full-length film. “I can’t wait,” he says. “It’ll be great.”

And as for why we don’t read about him more often. “You can get on the cover of so many magazines and that’s one aspect of the business. The stars do it because of the curiosity factor and the box office value. That’s not my way. Let the work speak, and then if it keeps up you might stay lucky and stay working.” ♦

I love this guy,a man;s man he is!