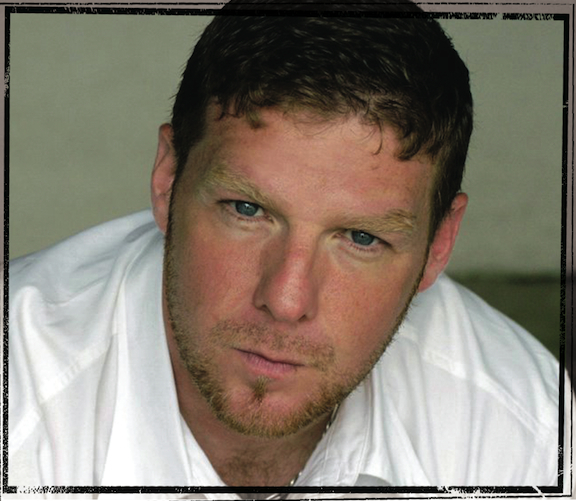

Michael Patrick MacDonald talks to Lauren Byrne about growing up in South Boston.

The last time I saw Michael Patrick MacDonald an air of tension swirled about him. It was 1999 and All Souls, his wrenching memoir of life in the notorious Irish enclave of South Boston, had just been published. The book had taken off like wildfire and Hollywood was calling, but in Boston it was a different matter. Hunched over coffee in a Newbury Street café he told me about the threats he’d received from Southie’s criminal element, upset with his revelations, and how at readings he’d been heckled by former Southie neighbors angry that he’d violated their time-honored code of silence.

Cut to an afternoon in September 2006. Michael is in Boston to give a reading from his latest work, Easter Rising, at the John F. Kennedy Library, on Southie’s doorstep. These afternoon readings attract the earnest and the well-heeled who typically fill a quarter of the auditorium. But on this occasion there’s not an empty seat in sight. After the reading, rock-star like, Michael vanishes in a press of bodies clamoring to shake his hand.

“It was an incredible homecoming,” he agreed when we met some weeks later. “I was scared to do anything that size in Boston. Everyone said, it’ll be blue-haired old ladies from Beacon Hill. But it wasn’t true. Three-quarters were from Southie, Dorchester, and the like.”

He looks hardly changed from the last time we met except that now he is infinitely more relaxed. Still, he hasn’t won over everyone. When he wrote an op-ed piece for the Boston Globe praising director Martin Scorcese’s depiction of Boston’s Irish mafia in The Departed, the paper was flooded with angry e-mails from real estate agents presiding over the creeping gentrification of Southie. It’s a much quieter place since crime lord Whitey Bulger vanished several years ago, but the area still has the highest drug arrest rates in the city. Other responses to his op-ed came from a still vocal element who, in Michael’s opinion, consider any comment on Boston’s Irish-American community a form of criticism. “People who persistently think I’m the enemy haven’t read what I’ve written,” he says. “Where I live today, and all the values that I cherish, come from what I learned in South Boston.”

The phenomenal success of All Souls was as unexpected as it was life changing. It made living in Boston impossible for Michael. “I’d go get a cup of coffee and someone would spot me and start hugging me and telling me their painful stories,” he remembers. “You couldn’t ask for more than for people to connect and confirm that you were right. But at the same time, it was too much to deal with. So I went to L.A. where nobody reads,” he adds with a grin.

Some people were born to be writers and then there are others who have a sensational story to tell, and once it’s written you never hear from them again. After the buzz around his book quieted down and Michael dropped out of sight, I’d often wondered which of the two he was. Figuring out what to do next after All Souls was a problem, he admits. In the meantime life provided plenty of distractions: Madonna took him to dinner and big-name directors and actors, interested in the movie possibilities of All Souls, kept him busy. But it didn’t last. “I had to get back to the East Coast”– he now lives in Brooklyn – “L.A. is so anonymous. Every car has tinted windows, even if the owners aren’t famous, to give the impression that they might be. As a writer it was difficult. You’re always fending off stories you hear in the day. There you’d go to a coffee shop and the conversations were about Mariah Carey’s breakdown or what Madonna was wearing at the Grammy’s. It’s just not good material.”

Easter Rising is Michael’s polished proof that he is indeed a writer. All Souls presented a story whose shocking details made for a red-hot page turner. In contrast, his new work is by turns lyrical, reflective, amusing, and wise. “Writing All Souls was an extension of activism initially,” he explains. “I was learning the power of storytelling when I was working with sibling survivors and mothers of murdered children, and of how it not only impacts the world but transforms the person who tells the story. With Easter Rising I was able to go beyond the guy who experienced horrific stuff and I wanted to enjoy the writing and the crafting and the structure of creating the story. And of course the story doesn’t really end. Because anytime anyone asks me, how did you get out, they’re asking it in the past tense, as if somehow I’ve achieved this plateau where all that tragedy is in the past. The truth of the matter is that it’s an ongoing process.”

In All Souls, Michael MacDonald was largely missing from the picture, serving mostly as the narrator describing life in the Old Colony projects, the quick succession of deaths that carried off several of his siblings, the racial tensions, political opportunism, and crippling crime problems of Southie. Easter Rising revisits some of those years, but this time such events provide the background to his account of how he came through it all.

He was 13 when he encountered the subversive strains of punk rock and responded to the thrill of it. Its initial promise of countercultural liberation showed him a way out of the conformity of Southie and its stifling culture based on such Irish tokens as plastic shamrocks and green beer. That some of his favorite bands, The Sex Pistols and The Slits, were English, the timeworn enemy in Southie, opened him up to a more complex view of the world – as did passing references to French poets and brie cheese. But the exuberance of punk didn’t save him from the nervous breakdown that accompanied his mounting family tragedies. In fact, it compounded his isolation. In 1985, stranded in England, where he’d gone to see some bands, his grandfather promised to wire him money only if he’d make a trip to Ireland. Having no options, he journeyed to relations in Donegal, where magically he was overcome by a sense of familiarity with the landscape and the people. With it came a new sense of identity, one that allowed him to connect with the Southie culture he’d always despised and to view the world beyond it with a new comprehension.

“The study of Ireland introduced me to the study of the history of colonization in general,” he says, talking about the degree in Irish Studies he subsequently pursued at the University of Massachusetts. “It brought me to India; it brought me to Africa. And it shapes how I view the racial issues we deal with today and the current political situation in Iraq – the new land to be colonized.

“It’s also helped me make sense of the tragedies I’ve experienced. Knowing where we come from is as important as knowing our genetic history. I was raised by someone and she was raised by someone, and somewhere in there the famine happened and the Easter Rising and the Black and Tans. So history is really wrapped up in how we’re raised. People who don’t know where the chip on the shoulder comes from, don’t know why they hit out at black kids on buses. They know they have a history of having their back up against the wall, but they don’t know why.”

Easter Rising reintroduces us to a familiar figure, Michael’s Ma, who’s set to become one of the most memorable characters in literature Her appearance in All Souls routed forever the inviolable image of the long-suffering Irish mother. Handy with a gun if necessary, ever ready for a sing-along, she lights up the page with the click-clack of her stiletto heels and the whine of her ancient accordion. Timorous readers may be secretly grateful they’ll only encounter her in print. Finding the right actress to play her in the All Souls movie for which Michael is writing the screenplay will be a challenge – though reportedly, there hasn’t been a shortage of actresses keen to step into her spiked heels, Susan Sarandon among them.

Mrs. MacDonald is an endless source of embarrassment to her son in Easter Rising, most memorably on a visit to England in 1998 where, in London’s Underground, she entertained passersby with her Irish rebel songs. In Piccadilly she commented loudly on the sad want of fashion among English people. But her complex identity and Michael’s growing appreciation of her are revealed when they travel to County Kerry and visit a family whose son died in suspicious circumstances in Florida. The Kerry family are silent with grief and bitterness until Mrs. MacDonald shows them that it is possible to live with loss and turn it into something life affirming. It can hardly be a coincidence that her son has managed to do exactly the same thing with his books.

In the following excerpt from Easter Rising, Michael Patrick MacDonald is a young child with his brothers and friends, finding ways to ride the train for free.

Going home from fare-jumping trips with Kevin and his crew was easier than the trip out. We’d walk from Filene’s to South Station and press the red stop button hidden near the ground at the top of a wooden escalator so ancient-looking that Kevin convinced me it was from “colonial days.” After we pressed the button, the escalator would stutter in its climbing motion and then come to a rolling stop. That’s when we’d run down the steep and treacherous steps into the station exit. Each wooden step was about one foot square, and I always wondered if people were skinnier in colonial times. At the bottom of the escalator was an unmanned gate that was often left wide open. But even if it was chained and padlocked, you could push out one fence post to make a gap, just enough to slip through. It usually took a bit of teamwork, but it was a cinch. Kevin was the scrawniest and could slip through without anyone’s help, so he’d go first and pull on the gate from the other side.

One day I discovered an even better way to get back home to Southie. Kevin was inside Papa Gino’s, pulling a scam he’d recently perfected. When the cashier called out a number, Kevin would wave a receipt from the trash, all excited-like, as if he’d won the lottery. His performance was so convincing — or maybe just distracting — that he’d walk away with a tray full of pizza and Cokes. Okie and Stubs would distract the waiting customers even further by asking if anyone knew where the bathroom was. I was outside on Tremont Street, playing lookout — for what I didn’t know — and daydreaming that Kevin would get a whole pizza pie. But Kevin cared more about scamming stuff for everyone else than for himself, and I knew he would give away his only slice if that’s all he got. While I was supposedly keeping watch, I spied groups of black people gathering nearby and then disappearing through an automatic door to a steel shaft sticking up from the sidewalk. As soon as one cluster of mothers, teenagers, and babies in strollers disappeared through the mystery door, more groups would gather around, press a button, and then loiter at a slight distance. They tried hard to look inconspicuous by rubbing their hands together or jumping up and down in one place as if they were cold, but I knew by their watchful eyes that they were just looking out, like I was supposed to be doing. The door opened, and again the busy sidewalk turned empty. I walked closer and saw through little steamy windows that everyone was squeezed like sardines onto an elevator and then whisked away to some place below Tremont Street. I pressed the button and waited for the elevator to come back up again so I could investigate.

“What are you, a fuckin’ losah?” Kevin screamed down Tremont Street just as the doors opened and more people looked around before hopping on. He was running toward me with a single slice of pizza, yelling at me for always wandering off. “You were supposed to keep watch!” he barked, grabbing me by the collar. Okie and Stubs were running behind him, pizzaless. They seemed like they thought they were being chased, and I told them to follow me. We squeezed into the elevator and pushed our way to the middle, surrounded by whole families of black people. Kevin punched me for staring up at them, even though there was nowhere else to look but up. In the end I would get high marks for finding a whole new and simpler method for getting a free ride home. The service elevator led from the street right into the subway system, beyond the conductor booths, and we all filed out nonchalantly. That day I earned the only slice of pizza Kevin was able to score.

In the days that followed I was so proud of my find I put the word out all over Old Colony Project about the new way to get home from downtown. That pissed Kevin off — he said the more people knew, the sooner the MBTA would cop on and shut us out. For a time the elevator was the one place in Boston you’d see my neighbors from Southie squeezed into a small space with black people. A key was required for the elevator to work, but the keyhole was always turned sideways, in the on position, either because it was broken or because some transit worker was doing us all a favor. Kevin and his friends didn’t care about leaving Southie except on scamming missions — they never went just to wander. And I could never get my own friends to leave the project, so it wasn’t long before I was venturing alone to see the strange lands and strange people beyond Southie’s borders.

From Easter Rising: An Irish American Coming Up from Under by Michael Patrick MacDonald. Publisher Houghton Mifflin. ♦

Was the screenplay ever turned into a film?

Thank you for sharing your stories, life with US lot.

Cannot wait to read more, peace

I honor your mother, Helen.sne. was a victim..of society..esp. used by men.I esteem your mother. because she never went into a back alley to have a abortion..kept her family going..she loved her children.she was unselfish..GOD BLESS HER..