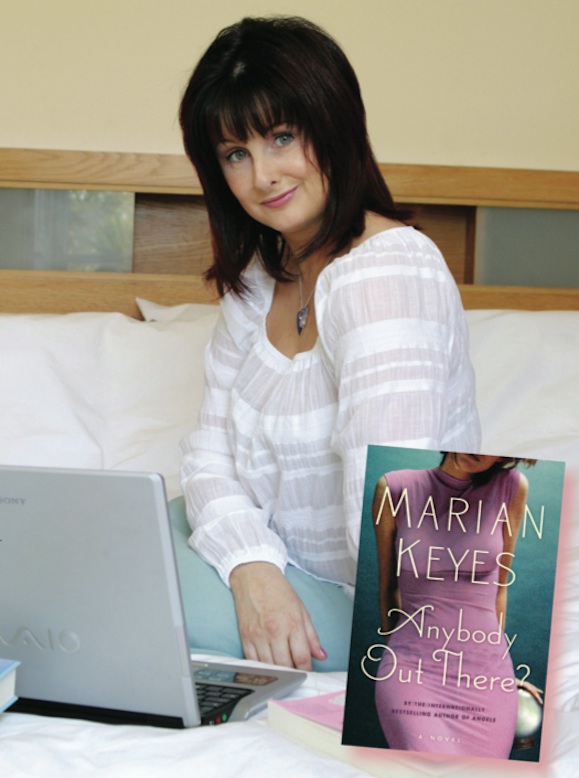

International bestselling Irish author Marian Keyes talks to Lauren Byrne about the other side of chick lit.

“Ask me anything,” Marian Keyes invited her audience at a recent reading she gave in Cambridge, Massachusetts, while promoting her latest book Anybody Out There? “I’m happy to talk about my alcoholism, suicide attempt, my low self-esteem.” Her listeners declined the invitation. Instead, “How did your family react to the sex scenes in your books?” asked a woman wanting to write but worried about her family’ s reactions. “Who reads your manuscripts?” asked another, having trouble getting anyone to assess her unpublished efforts. Keyes who last year, according to her publisher, outsold every other Irish and English author, responded to each questioner with encouragement, sympathy, and wry humor. Try getting that cozy with a literary author.

To the uninitiated, “chick lit” sums up a kind of disposable fiction à la Bridget Jones’s Diary and Sex and the City; all about airhead babes negotiating the minefields of office life, dating, and the January sales. But as this Q&A session made clear, chick lit is also a kind of candy-coated feminism. Keyes’ readers aren’t just being entertained: they’re being empowered to try to get into print too.

Which explains why Marian Keyes’ pretty features had clouded the day before when I’d tossed out the term “chick lit,” implying that her bestselling novels (nine to date, translated into 30 languages) were nothing more than escapist entertainment. We were sitting in her suite at Boston’s Ritz Carlton, a sign of how well chick lit authors do by their publishers, no matter what their critics say. Even the better known literary authors rarely rate the Ritz Carlton.

“Chick lit can be very helpful,” Keyes says, adding the qualifier, “if it’s done well. But the moment it [a book] looked as if it could be in some way potentially powerful the label ‘chick lit’ was slapped on it and instantly trivialized it. When I started writing in the early 90s I wanted to write about women like me. Women whose bosses were always male. I could see I had huge anxieties about my fertility and my relationship with my body. Why did I hate myself so much? Why did I have such a tortured relationship with food? And every other woman I knew was exactly the same.

“Women who read chick lit are often slightly mortified. They think ‘Oh God, I should be reading Philip Roth but these books let me know I’m not alone.’ I think the genre is judged by its worst books, by women who miss the point. They fetishize low self-esteem. When I write about low self-esteem it’s not to say it’s okay. On the contrary. When I write about relationships with men, it’s never to say we will be fixed by a relationship to a man.”

“Too female, too successful, too often in the bestseller list,” are the reasons Keyes gives for not belonging to Ireland’s literary scene. But Keyes is the best and certainly the best-known of an Irish chick lit scene. Writers like Patricia Scanlon, Cathy Kelly, Sheila O’ Flanagan, Sophie Kinsella, and Cecilia Ahern, whose work owes more to the Irish oral storytelling tradition than any literary inheritance, all have international audiences. All combine topics like death, depression, and domestic abuse with a large dollop of humor. Keyes believes Irish women have a particular facility for writing this kind of fiction. “I think we’re very realistic. We’re in tune with the darkness of life and we know that humor is our survival mechanism. It’s how I have coped with my var- ious stuff. Having to let go of alcohol, which was the love of my life, was excruciating. But when I ended up in rehab, humor was part of my day-to-day life.”

Several of Keyes’ books follow the fortunes of the Walsh sisters, who have in turn dealt with real life issues such as depression, addiction, and death. It’s the character of their madcap mother who seems to veer closer to wishful thinking. She’s an anomaly, if not a downright impossibility — an Irish mother who takes on board the details of her daughters’ sex lives without fearing for their eternal damnation. Keyes jokes with her audiences about her own mother’s facility with a red pen when she encounters sexy bits in her daughter’s novels. But when Marian’ s first novel, Watermelon, was published, Mrs. Keyes’ response was not so cheery.

“People like my mother were disgusted with my first book. But there were enough women to lock into it. So many women said, ‘Thank you for saying the stuff that goes on in my head.’ And they thanked me for articulating that Irish women have a sex life; that Irish women can be raunchy. I hope I’m not vulgar,” Keyes adds. “I never set out to be. But you know, we are sexual beings.”

Chick lit reflects the world of the average woman. But Keyes with her tumble of dark hair and her lively blue eyes has the look of an Irish fairy princess, and her own story, with its extremes of dark and light and its satisfying twist of redemption, has closer parallels to a mythological tale.

Born in the West of Ireland and raised in Dublin, Keyes earned a law degree in Dublin before moving to London where, as she quips, she put the degree to good use waitressing. Later she worked in an accounting office, where she almost achieved an accounting degree while hating the work. The knowledge that her contemporaries had all settled into successful careers drove her. She had not the remotest idea of writing. But in September 1993, the month she turned 30, she says, “I was drinking all the time; I was thinking about suicide a lot. It was in that hopeless space that I read a short story. I can’t remember what it was now, but I thought, That’s lovely; I really like that! It was as simple and as profound as that. Something had cracked open in me that tried to save me. I wrote a short story that afternoon. And quickly wrote four more. But I had no idea that I wanted to write – could write.”

The experience didn’t entirely rescue her. Early in the following year she attempted suicide and ended up in rehab, where she got sober. She still attends weekly AA meetings. “People misunderstand because they think ‘Oh you’re dying for a drink.’ But it’s not that I’m dying for a drink. It’s that I need help to live sober. Because for one reason or another I was born without the coping mechanism that other people seem to get. It didn’t help being brought up in Ireland in the 60s. It was such a reactionary place. The whole culture prevailed against women having any self-esteem. You weren’t encouraged to be confident. It was unseemly. My generation got out with our damage. My mother will never have that confidence.”

Keyes has plenty to bolster her self- esteem these days: a successful career, a happy marriage, not to mention the effects of the passage of time (“Turning 40 was great. Suddenly I was able to speak my truth without the worry that I would offend other people and they wouldn’ t love me anymore”). She moved back to Dublin eight years ago with her English-born husband, Tony, who now runs the business side of Keyes’ career. The children they’d hoped for haven’t come but now they are resigned to it, and instead keep company with two imaginary dogs, a conciliation to Keyes’ fear of dogs, which she’s working on. Together they travel five months over a two-year period, promoting her books. In her public appearances Keyes comes across as polished and confident, but in the pauses you can see the effort she expends to make her readers go away happy. That lingering sense of inadequacy has also contributed to her huge international success and is why if you check any Internet chat line about chick lit books Keyes’ name comes up more often than any other.

“The desire to please, the desire to be seen to be working hard is what drives me,” she admits. “I put a lot of pressure on myself to write the best book I can. I work harder and harder on each book. The first three books had so much from my own life. But more research is needed with each book.” She’s also determined to continue her feminist education. “I’m reading all the greats, Germaine Greer, Gloria Steinem. . . all the names I’d always heard of but never read. And anything new that comes out. I think women are terrified of the word feminism. They don’t want to call themselves feminists because it means that they’ll never get a boyfriend. That kind of stereotype of the hairy-legged humorless activist has stuck. I tried to do a course in women’s studies but they don’t do them in Ireland. There was just no demand. So I’m doing it on my own.”

Doing It on My Own. Sounds like a perfect title for – if you’ll excuse the term – a chick lit novel. ♦

Leave a Reply