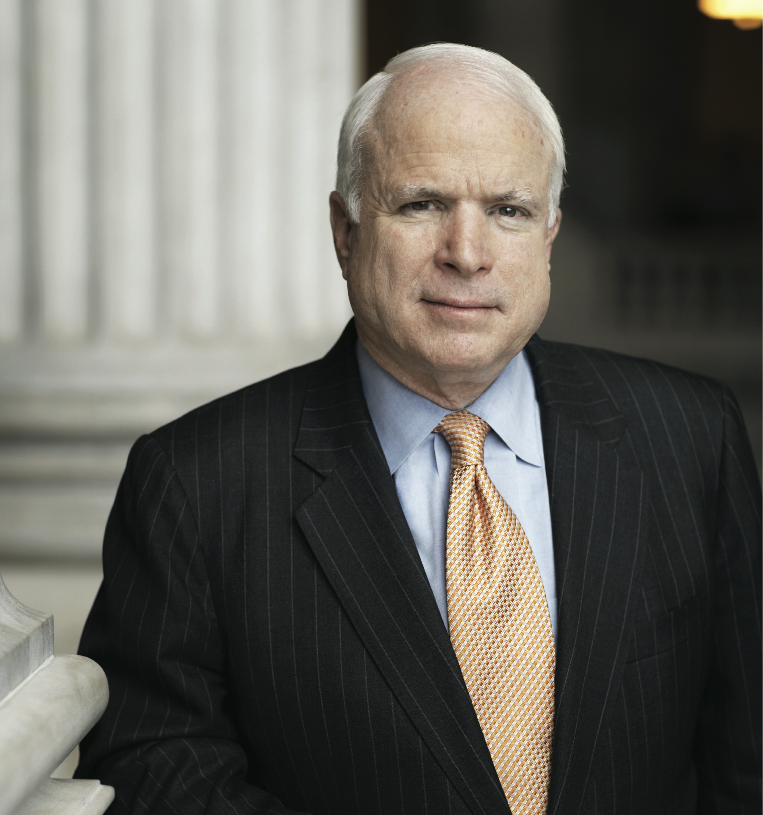

John McCain (R-AZ) is seated in his Senate office leafing through a dog-eared copy of John F. Kennedy’s seminal work, A Nation of Immigrants, written shortly before the 1965 immigration act which changed the face of America.

He is due to go before the Senate after our interview to speak on the controversial immigration reform issue. He has led the way on the issue to the fury of some in his own party who have attacked him. Worse for hard-line Republicans, McCain is inextricably linked with the antichrist Senator Edward Kennedy (D-MA), the Senate co-sponsor of the bill. John McCain is unperturbed, however. He is not known for walking away from a fight even with some of his own party members.

He explains why. He points to a photograph of immigrants arriving at Ellis Island late in the 19th century. There are people from every, clustered on the bow of a boat looking eagerly, expectantly at the new land they are arriving in. Their eyes are alive with heroic daring. “This right here is the promise of America,” says McCain simply. “Look at the faces, look at the hope.”

John McCain can connect with that hope. On his mother’ s family side, Hugh Young came over from Antrim in Northern Ireland early in the 18th century and settled in Augusta County, Virginia.

His father’s family, the McCains, bred to fight as Highland Scots of the Clan McDonald. Hugh McCain his wife and six children settled in North Carolina. Hugh and his four sons all fought in the American Revolution.

Both the McCains and the Youngs were descendants of Scots who, in the aftermath of Queen Mary’s death at the hands of her royal English cousin, suffered the forfeiture of those who had remained loyal to the Scottish crown.

No surprise then that the clan became famous in America as fighting men. One of their progeny is now favored by many to win the White House in 2008.

John Young, son of Hugh, served as a militia captain during the Revolutionary War, and was a member of George Washington’ s staff. Hugh’ s great-grandson, John Young fought the Confederacy during the Civil War, as did Hugh McCain’ s grandson, William McCain, who died while serving in the Mississippi cavalry.

Senator’ s McCain’ s grandfather, a four- star admiral, attended the surrender of the Japanese aboard the USS Missouri, during World War II. His father, John Sidney, also a four-star admiral, commanded three sub- marines during WWII, and was in command of all U.S. forces in the Pacific during the Vietnam War. Senator McCain himself, of course, was a heroic figure during the Vietnam War after he was shot down and held captive for five and a half years.

The McCains are a version of the American dream, the one where families distinguish themselves over generations in heroic service of their country.

McCain quotes from the Kennedy book at will, some by heart, and then says, “Every argument we are hearing in the Senate today on immigration was made back in the 19th century. It was made against the Irish, the Eastern Europeans. Everyone who was coming new to the country.” he says. “We need to know our history.”

Later on the Senate floor McCain would quote powerfully from the book to buttress his argument that the immigration bill he and Edward Kennedy had initiated in the Senate should be passed. Indeed, against all odds a version of it later was.

He points out in our interview that any party that is seen as anti-immigrant loses out eventually. He talks about the “Know Nothings” in the mid 1800s, the nativist group who targeted Irish Catholics and immigrants because they believed the Pope had designs on America and all immigrants were treacherous and unreliable. After initial success, the party utterly collapsed.

It is clear he believes there is a “know nothing” sentiment to the immigration debate in 2006 except the target of the hatred is Hispanic, not Irish Catholic. He knows too, if it is allowed to flourish in his party, Republicans will be significantly damaged. When former governor Pete Wilson in California went down that track over a decade ago, the GOP was decimated in subsequent elections in the state as Hispanics turned on them.

But McCain does more than quote from books on immigration in our interview. He talks emotionally about the little two-year-old Mexican girl found dead this year on the Arizona side of the border from heat prostration, and the 16-year-old pregnant girl, also found dead with rosary beads wrapped around her fingers.

“Doctors will tell you that heat prostration is a terrible way to die; the drug dealers don’ t die, the coyotes don’ t die. It is the innocents who are brought across by the coyotes who die,” he says grimly.

John McCain is a politician who feels an issue in his bones as well as dispassionately reading up on it in his briefing paper.

Recently, he read in the Irish Voice newspaper how a young woman from County Kerry, whom he had met a few weeks earlier at an immigration rally, had lost her young brother in a tragic car accident in Ireland. Because she was undocumented, she could not return home for the funeral and was forced to listen to the funeral mass down a phone line. He called her and empathized, a call most politicians would never have made.

McCain’ s stance on immigration is a risky one for a Republican from Arizona, a border state. His junior senator, Jon Kyl, has been virulent in his attacks on illegal aliens, as have several Arizona House members.

McCain, however, has led the charge among moderate Republicans for immigration reform, which would end the nightmare once and forever. His bill calls for legalization of those in America, and tough border security, as well as a crackdown on employers who hire undocumented, and a tamper proof identity card for everyone.

Not for the first time McCain is a minority voice in his own party, but polls show that a majority of Americans agree with him. In fact, opinion polls constantly show that McCain has the pulse of the American people more often than any other politician including the president. Yet to many he remains a mystery.

Perhaps Michael Kinsley of the Washington Post caught McCain best, noting in a recent column that he had the extraordinary ability in this very partisan time to have people, including many Democratic voters, overlook the issues they disagree with him on. Many Democrats, Kinsley believes, have a “girlish crush” on McCain. They excuse his anti-abortion position or his support of the Iraq war by saying, “Oh, he has to say that to get the Republican nomination.”

Maverick is a word that follows John McCain around like a puppy dog. It means he is that rarest of individuals in American politics, a man who thinks for himself.

It can be a costly label. His problem is the exact opposite of Hillary Clinton, his likely opponent for the 2008 White House race, if he gets the nomination. Many pundits say Clinton can easily get the party nomination but can’ t win, and McCain can’t get his party nomination but could certainly win if he does.

There are clear signs that McCain is reining in his maverick side in recent times, courting the evangelical wing of his party, being the good soldier when it comes to President Bush even as Bush’ s popularity collapses. He has taken his share of criticism for that. But there is only so far that he will go. Recently, he pulled out of a fundraiser for a strongly anti-immigrant Republican candidate in a San Diego congressional race. On that issue, McCain is not for turning.

Talking to him, or reading his autobiography, Faith of My Fathers, it is easy to see why. He sees himself living his life by the honor code that he learned at West Point and in the Navy and says that he has tried hard to never deviate from it.

It sounds like something out of the era of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table for those not acquainted with the American military and its mores. For McCain, it is his guiding light. “Duty, Honor, Country.” The three words are his mantra.

He admits that “It is hard in politics to abide by its precepts, but life is never more difficult for me than when I have strayed from those precepts.”

He admits he was sorely tested when he was a prisoner in North Vietnam after being shot down in 1967. When the North Vietnamese learned that his father was a senior admiral in charge of the Pacific Theater of Operations they offered to free him in order to embarrass the United States. McCain refused to be freed and was tortured unmercifully for the next five and a half years.

That was preferable to him than getting any special treatment. “My key for survival was emerging with my honor intact, with my faith in God, my country and my fellow prisoners intact. They tried to deprive me of my dignity but they failed.”

Asked if those were very dark days, he prefers to remember the lighter side of prison life, like his cellmate who figured because he found a carrot one day in his watery soup that they were all going home soon because they were being fattened up prior to release. “Now, that was viewing the world with optimism,” he says with a smile.

How does he look on the Vietnam War now? Most historians gauge it a failed venture that split Americans for a generation. McCain does not agree.

“It was a noble cause. What happened after North Vietnam prevailed clearly validated us. They executed thousands, sent tens of thousands to reeducation camps and brutally treated people. They have made progress now but there is still no freedom of expression. I have healed the wounds with them, worked with the Vietnamese on issues, but I still said, much to their dismay, not too long ago, that the wrong side won.”

But what if America had had to continue to occupy Vietnam in order to “win” that war?

“Well, we pretty much left because of public opinion, which was why the North Vietnamese succeeded. If we had stayed it would probably be like South Korea. Nobody minds, as we are not in combat there – and look how well they have done.”

Does he have any bitterness about how he was treated, enduring savage torture at the hands of the Viet Cong?

“I have no bitterness, it’s not a luxury I can afford,” he replies crisply.

But what if he met one of his captors, for instance the man nicknamed “Cat,” who was particularly savage.

“I’m sure I would feel a little emotion for what they did to me and my colleagues. There are some individuals I’m just as happy I never saw again, but overall I have made my peace with Vietnam.”

And the situation in Iraq today? How does he read that amid the cascading headlines of doom and gloom?

“Well, of course I’m worried, because the consequences of failure are so profound. We are a democratic country, we respond to the will of the people and I understand the frustration [of the people]. I do know that most Americans, although they want us out, do not support an immediate withdrawal. Part of it has been our own fault. All those optimistic statements, ‘mission accomplished,’ ‘last throes,’ ‘a few dead enders,’ have raised expectations and there has been understandable disappointment.

“One of our biggest failures was allowing the looting after the war. We never had enough troops to stabilize the situation… But there are huge stakes involved and the consequences of failure are huge, not just in Iraq but in the entire region.”

But don’t the optimistic statements coming from leaders today sound like what the generals and politicians used to say about Vietnam?

“In Iraq we now have a democratically elected government – in Vietnam it was revolving generals – so I think we have a chance for functioning democracy and government. Also, the support for the insurgents from Iran and Syria is nothing like the massive aid extended to the North Vietnamese by China and Russia. So this has to be fought as a classic counter-insurgency.”

What seems to bother McCain most, however, is the deep split in America now, not just over Iraq but so many other issues, too. Americans, it seems, have never been so divided.

“People are tired of bitter politics. Every time I think our approval ratings here in Congress cannot go lower I pick up a newspaper and indeed it is lower – 22 percent in one poll.”

Many believe McCain to be the one politician capable of bridging the divide.

Polls also show his numbers are high among Democrats and Independents too. McCain’ s biggest problem may be getting out of his own party primary system where conservatives dominate.

However, he is not yet prepared to publicly commit to the 2008 race. “I don’t know, I will decide in the next year sometime,” he says.

Those who know him best, however, have no doubt that he is running.

If he does, he says he may well cite the Irish economic miracle as an example of how successful economies come about. “Ireland has been an incredible success, it is a great argument for a strong educational system, for low taxes, for forward thinking.”

On his trips over there, he has increasingly felt at home. His favorite contemporary writers are Roddy Doyle, the chronicler of Dublin working-class life, whose books he can quote from and who he has met, and short story writer and novelist William Trevor. McCain had recently finished Lucy Gault, Trevor’ s book about a tragic Anglo-Irish family who mistakenly believe that they have lost their daughter.

He would also love to visit his forefathers’ home in Scotland, which he has never seen. Surely, as a part of a presidential run we can expect that he would visit the old sod, whether it be Scotland or Ireland, to stoke up the old ties and make new ones?

He smiles. It all seems so far in the future. An aide whispers it is time to go to the Senate floor to vote. John McCain walks out of his office past the bust of Teddy Roosevelt, the last great maverick in American politics who almost made it to the White House a third time as a third party candidate. Is John McCain the Bull Moose candidate of our generation? One thing for certain, the road to the White House runs past his door. Whether he decides to take it will likely determine who sits in the Oval Office in late January 2009. ♦

This article was originally published in the August / September 2006 issue of Irish America.

Note: After a comment from a relation of John McCain, received below, we made the appropriate changes to this article.

The first paragraph above mentions book, “A Nation of Immigrants”. This book deals with immigrants who legally entered the U.S. (as I did as a teenager), did not depend on any financial help at the expense of U.S. taxpayers, and did their best to productive and fully assimilate. It is highly unlikely that “An Nation of Immigrants” praises immigrants who refused to learn English,to familiarize themselves with the history, customs and culture of the U.S. , and whose first loyalty was to their own lhomelands.

Correction in the article regarding the McCains and when they arrived in the United States – the article says they came after the United States gained independence. The mistake is in the 5th Paragraph. I am a decendant of Hugh McCain he and his 4 Sons all fought in the American Revolution they were with General Washington at Valley Forge in the North Carolina regimine – They were from Terza North Carolina and are buried there. Hugh and all his sons. The article is fantastic and accurate other than that regarding the information I have on Hugh McCain.