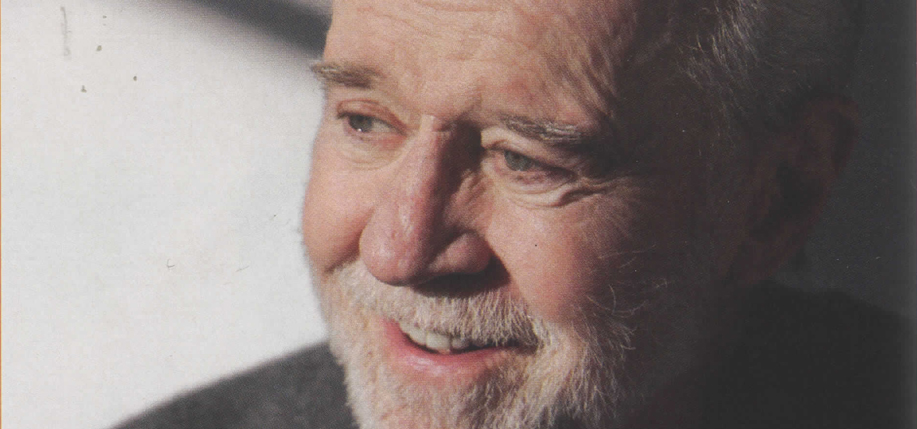

Once the quintessential seventies hippie comedian, George Carlin continues to evolve and grow. In an intimate interview with T.J. English he shares stories of his upbringing, his Irish ancestors and his view of the world.

In the history of American stand-up comedy, there has never been anyone like George Carlin. Controversial, iconoclastic, irreverent, obscene – all of these words have been used to describe Carlin’s act.

For nearly fifty years – in a career that has spanned radio, the heyday of variety-show television, albums, movies, cable television, books, and, most especially, live performance, Carlin has ruled the roost. In his career he’s had four gold albums, won four Grammy Awards, had three New York Times best-sellers, been given a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame and been inducted into the Comedy Hall of Fame.

Even with all the acclaim, Carlin, once the quintessential 1970s hippie comedian, continues to evolve and grow. His work draws new fans every year from the legions of youths who admire his scathing honesty and acerbic, anti-authoritarian point-of-view.

Carlin was born on May 12, 1937 to an Irish father, Patrick Carlin, and an Irish-American mother, Mary Bearey. He was raised on West 121st Street in a part of Upper Manhattan commonly known as “white Harlem.” Left to his own devices (Carlin’s parents split when he was two months old), young George learned about life – and developed his sense of humor – mostly in the streets, in a neighborhood populated by a lively mix of Irish-Americans, Puerto Ricans and blacks.

After battling a domineering mother, the priests at Cardinal Hayes High School in the Bronx, and later his commanding officers in the U.S. Air Force, Carlin launched his career in show business as a radio disc jockey. Once he established himself as a solo stand-up comic in the early 1960s, his career took off. Among the many highlights are his appearances on The Tonight Show – 138 times – thirty times as a substitute host for Johnny Carson – and hosting the very first episode of Saturday Night Live in 1975.

Despite a long career in the public spotlight, Carlin rarely does full-length print interviews. By his own account, he is mostly an “insular, solitary guy.” For thirty-six years he was married to Brenda Hosbrook, who passed away from liver cancer on Mother’s Day, 1997. Their only daughter, Kelly, was born in 1963. For the past eight years Carlin has been involved in a relationship with comedy writer Sally Wade.

In recent years, Carlin has cut down on his once rigorous tour schedule of forty states and one hundred cities a year. Yet he’s still out on the road performing at least eight dates every month, and he recently aired his thirteenth HBO stand-up special, Life Is Worth Losing.

Irish America caught up with the comic during a concert date in Chicago, on the eve of St. Patrick’s Day. Though he had only two months earlier spent time in the hospital for a heart condition (in his lifetime Carlin has had three heart attacks and five angioplasties) he was in a chipper mood. His memory was sharp, his mind lively, and his vocabulary as profane as ever.

℘℘℘

IRISH AMERICA: Let’s talk about your journey, an artistic journey that began on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, or “white Harlem,” where you were raised by a strong-willed, Irish-American mother. What can you tell us about that?

CARLIN: Well, first of all, I never knew my father. My mother left him when I was two months old. From what I’ve been told, he was a bully. He drank fiercely, and his personality changed. A street angel and a house devil, my mother called him. He never hit my mother because she had four brothers, and her father was a policeman. And bullies are usually cowards. But he menaced her, and she was from a peaceful family. The Beareys, my mother’s family, were very tranquil. So she was afraid of him.

Was there ever a time when the marriage was good?

There’s an interesting story about that. My parents had been separated about a year or more when they ran into each other on a New York street corner. They were always madly in love, my mother told me. He just couldn’t handle the drink. Anyway, on an impulse they decided to go and spend the weekend at Rockaway Beach, Queens. And that’s where I was conceived – at Curley’s Hotel on 116th and Beach Boulevard. By sheer chance, I was conceived.

So they reconciled for a time?

Not for very long. There was an incident. You see, my father’s profession was selling advertising space. First in the Philadelphia Record and then later the Philadelphia Bulletin. He made good money, about a thousand dollars a month during the Depression, and even more as time went on because he was so good at sales. My parents lived in a nice apartment at 78 Riverside Drive when I was born. They had my brother Pat, who’s five years older than me.

The way I heard it, my father used to drink at a place on upper Broadway on his way home from work. And he’d get juiced. He’d come home and he’d be his usual f**ked-up self.

Now, my mother was a woman from humble beginnings with lace-curtain Irish pretensions. She insisted on having nice things – fine crystal, fine silver, mahogany furniture, good linens. She was obsessed with that shit. She didn’t like the shanty Irish. In later years she talked about my father that way. “Dirty shanty Irish,” she called him.

So she’s waiting for him to come home for dinner this one night. It’s July of 1937 and I’m two months old. He comes in, and they’re going on, fighting like crazy.

Now, I’m sure she was a handful. My brother and I have discussed this over the years and decided she was probably a handful for this guy with her aristocratic pretensions and so forth. I mean, she had a little bell that she would ring at dinner to change courses. This f**kin’ Irish woman from downtown, from Chelsea, and she’s ringing a bell!

So my father comes in that night and they’re going at it. She says something like, “What’s the point of having all this nice stuff, this good crystal, these lovely place settings, if you’re going to come home drunk?” And he says, “You like the nice stuff, do you?” The window is open; it’s a hot night in July. He picks up the tray with a silver tea set or crystal, something “fine,” and holds it out the window. He says something like, “Here’s your good stuff.” Then he just drops the tray.

Well, my mother gathered my brother and me together right then and there and left. She went to her father’s house on West 112th Street, where he lived alone, and took refuge there. My father knew where to look, of course. He came after us and broke down the door at one point. The next day my grandfather had a stroke and died, for which my mother never forgave my father. He continued with his hassling and menacing until one night she went out the window with me in her arms, and my five-year-old brother holding her other hand, down the fire escape, through the backyard and out to Broadway where her brother, Uncle Tom, was waiting in his Packard. She never looked back, except for the separation and the court proceedings and the alimony that my father never paid. It was only five bucks a week but she couldn’t get it out of him, because he was spiteful.

You have to admire your mother’s fortitude.

Absolutely. She was way ahead of her time with this single mother shit.

Did you ever see your father after that?

For a brief time he had visitation rights. Every Sunday, I think it was, he would take my brother Pat and myself to Cannon’s Bar on 109th and Broadway. I was maybe one year old. He’d set me down on the sawdust floor, crawling around, and sit Pat on a bar stool and give him a Coke. Then he’d proceed to tell stories. He was a great storyteller. On one of those Sundays, he knew the visitations were coming to an end. He wasn’t making the payments and Mary had been forced to take legal action. I remember us on the living room floor, me an infant. He held me up with his hands and sang “The Rose of Tralee,” which has such beautiful lyrics.

So this was his farewell to you?

That’s what it was. And, those lyrics, they don’t apply to me in any way, but they were about Mary. In his own way, I think he was saying goodbye to Mary through me. In later years, to explain his absence, they told me he was over in the Pacific helping MacArthur win the war.

Your father passed away suddenly from a heart attack when you were just eight years old. Do you ever think that if he’d lived longer, and you’d had a chance to come to terms with him in some way, your life and career might have been different?

The thing is, I never really had “issues” with my father because I was so young. My older brother Pat did. He abused my brother Pat for five years with spankings. Any kind of minor infraction, the slipper came out and the spankings began. My brother hates his guts. I hate him by proxy, but I also love him by proxy.

But would the career have been different? I hope not. I think I would have headed in the same direction as an entertainer. I think he would have liked that and supported me, unless, of course, some knee-jerk parental impulse made him object to a career with such long odds of success.

You’ve talked often about your “genetic tool kit,” how you inherited a love of language that has become a defining aspect of your work. Did that come from your father or your mother?

From both. My father was born in Donegal Town on January 11, 1888. His father, Pat Carlin, was from Tyrone and Donegal. My father was a champion public speaker. I still have the mahogany gavel he won for taking first place in the Dale Carnegie Public Speaking Contest of 1935 with a speech called “The Power of Mental Demand.” My mother was very proud of that. Even though they didn’t get along, she loved telling the story of how, in a packed ballroom at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, he used to end his speech with an index finger extended and his arm sweeping across the audience, and he’d say: “The power of mental demand. You all have it. Put it to work.” You know, he was that kind of dude – an accomplished public speaker.

So without ever knowing him, you got his gift of gab.

I got his gift of gab. And my mother’s. She was very verbal, very funny, and she had a quick mind. She was the one who loved the dictionary. If I ever asked her about a word, she’d say, “Let’s go look it up.” And she talked to me about all the great Irish writers, about their gifts with the language. She would tell me about Oscar Wilde and George Bernard Shaw and Yeats and Beckett.

But no Joyce?

She mentioned Joyce. I don’t think she was into his work so much, but she liked the fact that he was revered and he was Irish. And then O’Neill. She saw all the Eugene O’Neill plays, which I think are now dated and a little overwrought but nonetheless full of good Irish drama and rip-roaring fun.

So there was a strong sense of Irish pride around the house.

I was watching the St. Patrick’s Day Parade today here in Chicago, and that reminded me of the whole Irish pride thing. It makes me emotional, but then I can get emotional over a nice set of matching luggage. I have this real close to the surface – the Irish sentiment and emotionalism.

Did you make the inevitable journey back to the Old Country?

My first trip there was in 1980 with my wife Brenda. I remember seeing for the first time all the wonderful little towns, and all the business establishments, mostly bars but others as well, with the beautiful hand painted signs – O’Connell’s or P.J. Leary’s or Driscoll’s. We’d be driving on a morning and come across a horse show. So we’d stop and watch the Irish kids interact with the horses, which was great fun.

Most of all I remember the faces, the wonderful faces. I remember thinking, “I know these people. This is my herd.”

Near the end of the trip we went to the West of Ireland. Near the Lakes of Killarney – I forget which lake – I dug up a big clump of sod, put it in a zip lock bag and brought it home. I planted it in my yard in Brentwood, in Los Angeles, and it actually grew and thrived for five or six years.

From very early in your adolescence, you seem to have developed a rebellious streak, particularly in relation to the Church. Any ideas where that started?

It wasn’t so much rebellion as a growing disenchantment. And disbelief. It started with my first Holy Communion. They told us it was going to be this transformative experience, the feeling of God in our bodies. The happiest day of your life. Well, none of that happened. It was just another day. The seed was planted in my mind: “Oh. Maybe these people don’t know what they’re talking about.”

And then there was your time at Catholic school.

Yes, well, my mother, God bless her, she was determined that I have a good Catholic education. It appealed to her sense of upward mobility. The interesting thing is that the grade school I was sent to, Corpus Christi, was very progressive. It was run by the Sinsinawa Dominican nuns. The classes were small, and there was no grading system as such. The nuns were wonderful. They taught you to think for yourself and to discuss things. They gave me the tools to reject the very religion they wanted me to have.

The funny thing is that, in later years, when my career in entertainment took off, some of these nuns would come to my shows. I remember my mother was having a terrible time with my material. She ran into some of the nuns from Corpus Christi and voiced her concerns about the “dirty language.” They were the ones who told her, “No, what he’s doing is using those words to analyze things. To expose the hypocrisy.” Well, now my mother had to completely reevaluate her position. The nuns, who she respected, were telling her that what I was doing was okay. Once they endorsed my material, she had no choice – she had to accept it.

Your time at Corpus Christi sounds like a paradise compared to what you went through at Cardinal Hayes High School in the South Bronx.

Yes. Here I was dealing with the Irish Christian Brothers, and they were not like the nuns. First of all, they were male, and that was a whole different feeling. And they would hit you for not doing your history homework, or for just about anything. And they would berate you. So I started cutting classes. I believe I had a sixty-three-day hooky streak, which must be a record. I failed five subjects because I didn’t do the homework. I just didn’t give a f**k.

At the same time you were flunking out of school, you were engaged in a kind of culture clash with your mother, who wanted to mold you into an image of the man she wanted your father to be, a respectable, middle-class businessman. But you had other ideas.

Some of this goes back to growing up without a father. I think the psychologists call it the presence of an absence. Or is it the absence of a presence? Anyway, on top of not having any “adult male supervision” – as if that were the solution to everything – my mother was at work all day in a responsible job in advertising. We had a lady who looked after me until I went away to school, and the neighbors and playmates looked out for me, but I had a large degree of independence and autonomy to form my own personality. And it was out in the streets that I became attracted to comedy. I found out I was a good little mimic. You know, when you do something when you’re young and all the adults think you’re wonderful, you’re getting an audience, you’re getting approval, applause, that becomes your calling.

But also, throughout your early life you’re clashing with institutions. You have problems with your mother, the Church, school, and then the U.S. Air Force, where you were court-martialed three times before being discharged in 1957. Later, your hostility towards institutions in all their many forms becomes a foundation of your comedy.

I can’t deny it; having a problem with authority has stood me well over the years.

Early in your entertainment career you clashed with authority in a big way when you offended Cardinal Cushing in Boston. Tell us about that.

It was during my radio career in the late fifties. I was a disc jockey at WEZE, a big NBC affiliate in Boston. Cardinal Cushing used to buy fifteen minutes of radio time from 6:45 to 7 p.m. to recite the rosary, which was big in an Irish Catholic town like Boston. One night, the cardinal was on there with a voice that sounded like it was coming out of a sepulcher, and he’s talking about the Little Sisters of the Poor and the wonderful work they’re doing in Uganda or someplace like that, somewhere overseas. I’m in the booth operating the board, and I notice the cardinal is running late. At 7 o’clock I’ve got what’s called a hard break. I’ve got to go to a five-minute newscast. I have an FCC log in front of me and it’s in red, which means it’s paid-for commercial time.

So the cardinal’s now into the sorrowful mysteries or glorious something-or-other. He’s praying, “Praise the Lord Jaysus holy Lord holy Mary mother of God Jaysus in heaven. Holy Mary mother of God pray for us sinners now in the hour of our death…” And he’s dragging on. I can see he’s not going to be finished at 7 o’clock. But I’ve got no choice. This is commercial time paid for by Alka Seltzer. So as the hour approaches, I do what I always do. I turn up the network and fade down the broadcast.

Well, within a minute or two the phone rings. I answer, and there’s that voice: “I would like to speak with the young man who interfered with the Word of God.” I said, “That would be me.” I can’t remember if I called him Your Eminence or just Cardinal. Anyway, I got called on the carpet, but our internal organization backed me up, kind of. They told me I was just following the FCC log like I was supposed to but that it probably wasn’t the best political decision.

So you were “interfering with the Word of God.”

Isn’t that great? I wore that like a badge of honor for years.

In Boston you also met Jack Burns, another Irish-American, and formed your first comedy act, Burns and Carlin. Rather boldly, the two of you headed off to Hollywood and are soon discovered by the most daring stand-up comic alive, Lenny Bruce.

Well, there is a little more to it than that. What Jack and I did at the time wasn’t really cutting-edge or anything like that, but in our own way we were trying to be hip, brash comedians making a statement. We did stuff about integration, the KKK, the freedom riders; anything in the news was fodder for us. I did two impressions in our act: Lenny Bruce and Mort Sahl. Our manager, Maury Becker, knew Lenny from the Navy. And sure enough, Lenny showed up one night. He had a beautiful powder blue jacket on. I’ll never forget that. I did my impression and he was positively impressed by the act itself. It was because of Lenny’s good word that we landed an exclusive contract with a major talent agency.

What was it about Lenny Bruce that had such a powerful influence on you?

It took a while for Lenny’s influence to become apparent, but I could see that in everything he did there was an honesty and an ability to be candid and open and nonhypocritical about culture and institutions. That appealed to me. That you could stand on stage and challenge these things, that you could examine the use of language and say intelligent things and not just tell jokes. So I had that conscious recognition of Lenny’s brilliance. I couldn’t get it to work right away in my own act, but I stored it in the developmental part of my head.

In 1962 you split amicably from Jack Burns and almost immediately you started to have success as a straightlaced stand-up comic. Your signature bit was “The Indian Sergeant,” which you parlayed into appearances on The Ed Sullivan Show, Steve Allen, Merv Griffin, The Tonight Show – all the major television shows at the time. You landed a contract to play Las Vegas. Things were going well. You should have been happy, but you weren’t. What was wrong?

There was a growing unease on my part about where I’d wound up. Throughout the sixties I began to notice that I had a bi-level existence, an A and B level. My A level was the young kid who wanted to be an entertainer like Danny Kaye. I wanted to be famous and make people laugh. The B level was my life as a pot smoker and a rule breaker and middle finger extender to the authorities. I felt that the pot smoker, law-breaker, outlaw type was the real me, but that clashed with the dream I’d had for myself from when I was young. I began to see that the two didn’t go together. In order to be Danny Kaye you have to please people and play the game, and I was anything but a game player and a people pleaser – though I wanted applause and positive attention.

It was only when I took mescaline in the late sixties that these things opened up in my mind, just as they did for so many musicians I knew and others of that generation. It attuned my mind to the fact that I was in the wrong place. It was 1967 during the Summer of Love. I was thirty years old, but the people I was playing to in the nightclubs and on the Vegas strip were forty and above. I was now more interested in connecting with people who saw the world the way I did – the college kids. So, like a heliotropic flower, I started to bend towards them. And I found in me the things that had always been there. I found this voice of anti-authority. And I was capable by then, with my facility for writing from having done stand-up for years, to put these thoughts and ideas into coherent form on stage.

The transition you made from being a suit-and-tie kind of entertainer to the long-haired hippie comic was stunning. I remember as a thirteen-year-old kid watching you on a TV variety show walk out on stage for the first time with long hair and a tie-dyed t-shirt, holding a cardboard cutout of the old George.

I so much wanted people to see the logic of what I had done. I didn’t want people to think that I was an opportunist. I know some people in show business said, “Oh, he’s just trying to cash in on the hippy thing.”

Like it was a phase or a craze.

Right. And I knew how untrue that was. I even did a number of coffee house gigs for free, just to prove that the transition was sincere and the work would reflect that.

The seventies usher in what would be the most commercially successful phase of your career. You put out AM &FM, Class Clown, Occupation: Foole, Toledo Window Box – four gold records in a row. I guess the classic bit from this era would have to be “The Seven Words You Can Never Say on Television.”

Yeah. It’s now something people refer to even if they don’t know the origins of it.

What can you tell us about the origins of this landmark routine? It became the impetus for a famous free speech ruling when WBAI radio in New York was fined by the FCC for playing “The Seven Words” on air. WBAI challenged the fine in court. “The Carlin Case,” as it became known, went all the way to the Supreme Court.

I don’t know it seminal is the right word, but this was the piece that summed up a lot of what I’d been grappling with in the mainstream television world of variety shows and internal censorship. Part of it is that 1 have this orderly left brain. I have a right brain that’s pretty active, too, but it’s the left brain that saved me as a child. So, that part of my brain likes to put things in order. It wants lists. It wants indexes. It wants categories. It wants a system.

At the same time, it occurred to me that not all dirty words are dirty all the time. So I made a formal list. I noticed that “bitch” and “bastard” and “hell” and “damn” could be used some of the time on the broadcast media in certain contexts. They couldn’t be used in other contexts. But the words themselves – it was so important for me to point out that the words are not the problem. The definition, the context, the intention of the speaker, those are the things that make them good or bad. So I wanted to kind of say that. I don’t think the word “teach” ever entered my mind; it never does. But it was an act of teaching. I found that I could make the distinction between the words you could use some of the time: “ass” you could say, “nuts” you could say. “Balls.” “Box.” All these are potentially dirty words that have clean meanings.

You could prick your finger, but you can’t finger your prick.

That’s great. What a great economy of words. “You can prick your finger, but you can’t finger your prick.” I’m so proud of coming up with that.

The success you experienced in the seventies brought about all kinds of personal problems, which you’ve talked about in the past. Two heart attacks that may have been brought about by the cocaine use. You and your wife’s problems with alcohol. Were you beginning to feel like you had lost the narrative thread of your career?

Well, I think most artists experience that as a slowdown, a transition. But the public views it as, you know, “He’s finished.”

There’s no doubt that my work had begun to lose some of its edge. I’d made the four gold albums in a row, then two that weren’t gold. My creative impulses, my hotness, cooled off. You’re never the fastest gun in town forever. Sooner or later there’s a faster gun. I was no longer the new guy. I became introspective. My humor became more observational: “Did you ever notice?” “Have you ever thought about…” That sort of thing.

Overall, my career was doing fine. After a rough patch in the late seventies and early eighties I was doing a new HBO show every two or three years and touring. I had a new record out – A Place for My Stuff. The work was solid, but it wasn’t really what you would call cutting edge.

What re-ignited your creative juices?

One watershed event was when Sam Kineson came on the scene in the mid eighties. That was the second time another comedian’s work shook me up and made me take notice. The other one was Richard Pryor.

See, when I see another comedian, there are two reactions I can have. One of them is, “That person’s not a threat.” And the other is, “Oh, I better get busy.” When I saw Richard’s first concert movie, Live at Sunset Strip, my reaction was, “I gotta get busy.” Richard raised the bar. It was like that with Kineson. It wasn’t so much the content of his material but the experience of watching his rage on stage. I remember thinking, “Oh. It’s a noisy culture. You have to raise your voice.” And I meant that both figuratively and literally.

The nineties began a new creative period for you that continues to this day. The work has gotten darker, harsher, more pointed in its critique of American culture and the screwed-up nature of the human species. Is it possible to pinpoint where this new persona first emerged?

For the 1992 HBO show Jammin’ in New York, we got together 6,500 people at Madison Square Garden, not the big arena but the adjoining Paramount Theatre. It’s live – first time we did one live. And it’s my hometown. I think that was the one where I was finally a writer doing his own version of stand-up. The pieces were well compartmentalized and thought out. I was beginning to crest a bit creatively, and the tone had changed.

Have you become more angry?

I don’t experience what I do as anger. I don’t think anyone who’s ever been around me much would say I am an angry person. I don’t lose my temper. I’ve never been in a physical fight in my life. Sure, like anybody else, I get irritated in traffic or if a line moves slowly. I’m sure there have been exceptions to all these things I’m saying, but for the most part I don’t live an angry life. What you’re seeing on stage is a person in a heightened state. You need to heighten and project and theatricalize to make the act work.

Also – and this is probably the most important thing – what many people identify as anger, I would probably call discontent or disappointment with my species and my culture. I feel betrayed by them. Betrayed by my church, the business world, you name it.

But there’s certainly more hostility in the work. And it’s often times hostility directed at the audience.

That’s true. Yes. I never frame it as, “Look what they’re doing to us.” I think of it as, “Look what you’re doing to yourselves.” Even though I will point the finger at business and government and religion as screwing with people, generally people allow that to happen. It’s called “We the People.” It’s called self-government, so take the f**king responsibility. Take the blame.

Any concern that with this more lacerating approach to your audience that you may be alienating people who have been with you along the way?

When that does cross my mind, which is not infrequently, I always tell myself, “Well, good. They’re the ones who don’t belong on the ship.” Whenever you lose one, you’ll pick another one up. I have always enjoyed, and still do, finding the sensitive areas for my audience. Finding their soft spots, their red buttons, and pushing them. I feel that as long as I have sound ideas, a sound underpinning of argument and analysis, then there’s nothing I can’t or shouldn’t talk about. For instance, people say you can’t joke about rape. Rape’s not funny. I say, okay, imagine Porky Pig raping Bugs Bunny. That’s funny, isn’t it?

I’d like to conclude with a short quote from your daughter, Kelly, who says of you: “In his own way, he’s trying to make the world a better place.”

It’s perverse, but it’s true. That’s her wisdom. She sees a side of me that I often don’t consider at all.

So, to those who call you a cynic, you say…?

I don’t experience it as cynicism. I experience it as realism and skepticism. Besides, who was it that said if you scratch a cynic you’re liable to find a disappointed idealist? I don’t know who said that, but it’s a wonderful sentiment. ♦

I remember hearing his “7 Words” album in HS, and I saw his premiere performance on SNL. He was and remains an icon for me.

I can’t even imagine what he’d be saying about “we the people” today, but it would be spot on.

This is my herd!

A complex life story, yet clearly understood. I have enjoyed George Carlin over the years and understand his clever abilities and sense of what needs to be truthfully, shared.