Immigration into the Republic of Ireland has begun to push the troubles in the Six Counties of British-occupied Ireland off the political agenda in Dublin. It is the latest “hot button” issue.

Long familiar with the economic, social and political consequences of emigration from Ireland over the centuries of English rule, the Irish body-politic now faces increasing strains and stresses from the mounting flow of both legal and illegal immigration into the economically booming 26-county Republic.

Since the enlargement of the 15-member European Union in 2004 by the admission of former Communist countries in Eastern Europe, plus Malta and Cyprus, a previous growing but manageable number of immigrants has turned into a veritable flood. Only Ireland, the United Kingdom and Sweden among the “old” E.U. states agreed to accept unlimited immigration of labor from the “new” E.U. states from the start.

Sweden, under pressure from its powerful trade unions, modified this “free for all” policy almost immediately, leaving Ireland and the U.K. as the primary destinations for hundred of thousands of young, largely English-speaking, well-educated, highly motivated, and physically fit immigrants. The figures are stunning. From the date of accession of the 10 new member states (January 1, 2004, but free migration from May 1, 2004) to December 31, 2005 some 165,516 applications for work permits were issued in Dublin and the current figure is running at 12,000 per month.

These “new Irish” are being rapidly absorbed into the fastest growing economy in Europe, with a per capita Gross National Product (GNP) higher than the United States. In this regard, Ireland passed the U.K. several years ago.

In addition to Eastern Europeans, a large number of Filipinos now make Ireland their home.

The crumbling national health service, suffering from maladministration and plummeting standards since the disappearing religious nuns gave over control of many hospitals to state-appointed lay people more interested in pay, promotion and pensions than patients, has had to streamline normal immigration and regulations in order to recruit thousands of Filipino nurses to fill the gap.

Tourists will note that there is scarcely a town or hamlet in Ireland without its Asian restaurant. The number of Chinese is expected to equal two percent of the population in the next census, all busy feeding an increasingly cosmopolitan consumer society. Altogether, 400,000 of the four million population are foreign born. In percentage terms (10%), this is about equal to the number of foreign born in the United States.

For those who must sell their labor, however, there is a serious downside to this rosy picture. Competition in an open labor market of four million Irish and 75 million Eastern Europeans will inhibit pay and conditions for existing Irish workers outside the sheltered civil service. This was dramatically illustrated in the recent strike which brought Irish Continental Ferries to a complete standstill. An all-Eastern European crew and officers were recruited to replace their Irish counterparts. So large were the savings in wages, however, that the ferry company was able to offer a severance package generous enough to gain 90-percent acceptance from the redundant Irish workers.

The principle of out-sourcing existing Irish employment to Eastern Europe was established. Only the price was to be negotiated. The redundant workers cried all the way to the bank.

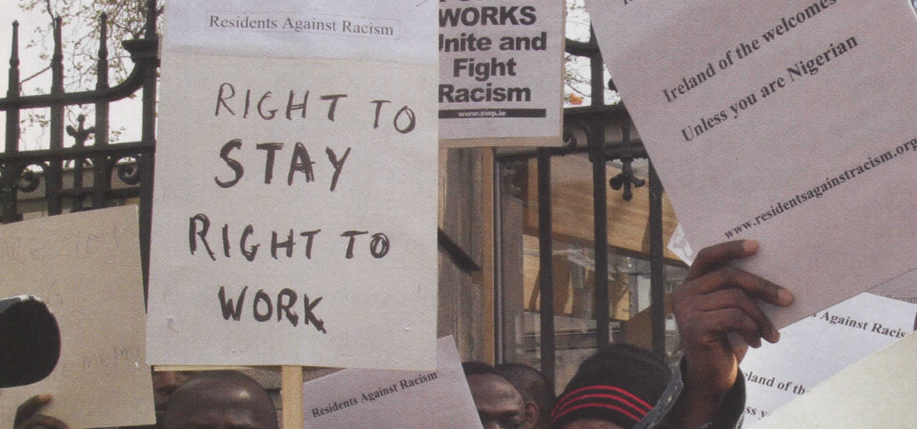

Yet another aspect of the rapidly changing face of Irish society was brought into sharp focus when an archbishop of the Anglican Church of Ireland, once the last redoubt of Anglo-Irish influence, issued an appeal to the government requesting amnesty for illegal immigrant residents in the country for five years or more. No doubt the archbishop’s appeal was based on the highest Christian doctrine of sanctuary. It did not miss the attention of many, however, that one of the largest concentrations of illegal immigrants are from Nigeria, a former British colony. Nigerians now make up an increasing percentage of the growing “all singing, all dancing” Protestant congregations in Ireland.

The challenge for Irish society today is to manage the seismic shift from a homogenous society, based on cultural and ancestral consanguinity, to one of diversity. It sounds simple, and has that politically correct warm and fuzzy feel to it, but few, if any, societies have been able to make that transition peacefully or without destroying much of the fabric that made it attractive to begin with. Assuming of course that the motor car, the Irish construction industry, a scandalridden Catholic clergy, and the dissolution of the traditional family (fully one-third of all Irish children are now born outside marriage) don’t accomplish the job first.

As the poet Yeats wrote:

Romantic Ireland is dead and gone,

It’s with O’Leary in the grave. ♦

Leave a Reply