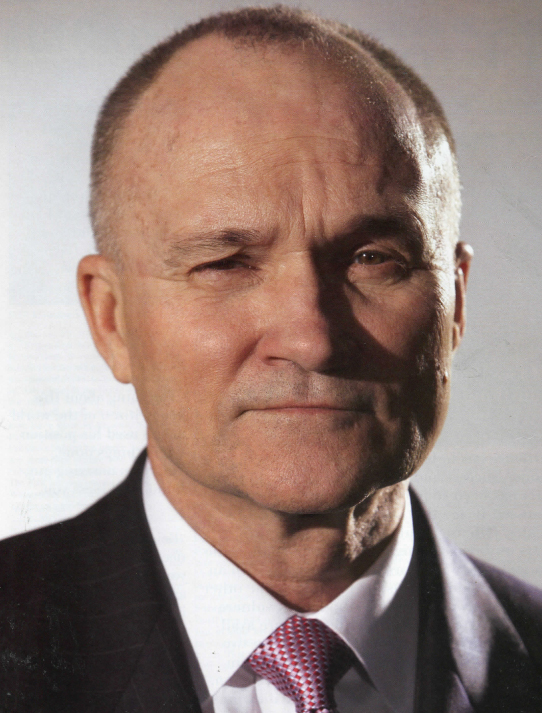

At the helm of the NYPD, the nation’s largest police force, which is acknowledged as an international model for its cutting-edge crime-fighting techniques and facing down terrorist threats, is Police Commissioner Ray Kelly, a former Marine who likes a challenge.

Ray Kelly recalls how when he was only seven years old. he’d often hop on the subway and travel down the West Side of Manhattan alone to have lunch with his mom who was a coat check girl at Macy’s, the nation’s biggest department store.

His dad, James Francis Kelly, spent twenty years as a milkman, first driving a horse-drawn carriage over cobblestone streets and later upgrading to a standup motorized half wagon.

Today, Ray Kelly’s intrepid journey has taken the son of a milkman from Hell’s Kitchen to the top of the New York Police Department, the biggest police force in the country.

In the dark days after 9/11, he was tapped by Mayor Michael Bloomberg to return as Police Commissioner as the city came to grips with the new reality of the world.

He is the only man in the 160-year history of the NYPD to twice serve as its Police Commissioner in two separate stints. He’s a cop’s cop, the only man to have held every rank in the department, from rookie patrolman to Commissioner, in a 31-year career.

“Since he came back in January 2002. less than four months after the 9/11 attacks, he basically created a whole new police department with a new role, placing the department at the front line in the defense against terrorism.” said Jeremy Travis, president of John Jay College of Criminal Justice. Travis, who has known Kelly for more than twenty years, says. “He may very well be the best commissioner the department has ever had.”

John Timoney, a Dublin-born cop who served for years with Kelly in the NYPD and now serves as the Police Commissioner of Miami, likened the department that Kelly inherited to a “brand-new Cadillac with a ceased engine.”

“I knew he could fix the internal problems because he’s a perfectionist, and nobody knows the culture of the NYPD better.” says Timoney, “but 1 didn’t know if the crime rate would continue to drop.”

In Kelly’s first term as Police Commissioner under Mayor David Dinkins (1992-94), he began work on reducing the homicide rate that had soared in the city to 2,245. Last year the murder rate sank to 549 – the third year in a row that the numbers went below 600, and the lowest tally since the statistics were accurately recorded in the mid-1960s.

Overall crime rates are at their lowest in decades. And a great deal of the credit is due to Kelly, who accomplished this mission of keeping New York safer with a substantially reduced staff.

Ray Kelly is a man who takes charge while retaining the loyalty of those who work for him. His formative years were spent in the Marine Corps.

“We were all Marines,” recalls brother Donald, seven years Ray’s senior. (Ray is the youngest of five – four brothers and one sister.) Older brothers James and Kenneth had already enlisted. “We just followed each other. It was a natural thing. You follow your brother,” Donald said.

By the time he was 23 years old, Ray Kelly found himself stepping into a combat unit in Vietnam as a lieutenant. He retired from the Marine Corps reserves as a colonel in 1993.

“My experience in the Marine Corps shaped my life, gave me discipline, perspective, a view of the world that I use literally every day,” says Kelly. His spit-and-polish black shoes, starched white shirts with French cuffs and meticulously knotted Charavel ties (sold to him for years by ex-Marine Dan Hirsch at Bergdorf Goodman’s) have become a trademark which some attribute to military discipline, or maybe the nuns at St. Gregory’s.

“The single biggest argument I have with him is that he doesn’t believe in anything other than white shirts and black shoes.” said attorney-about-town Eddie Hayes, another longtime friend.

“He’s extremely disciplined, unlike most of the Irish who are pretty free wheeling,” said Timoney. “While he’s true-blue Irish, he plays it close to the vest.”

Despite his background as a second-generation Irish-American with working-class-roots, Kelly was the first member of his family to enter the NYPD. “I guess I disprove the notion that you have to know somebody to move up in the Police Department,” says Kelly. In the department, it is known as a “hook.” But Kelly clearly forged his own hook out of pluck and determination.

Joe Lisi, a retired police captain and ex-Marine, met Kelly when he was working on one of the city’s first anti-crime units in the 23rd Precinct in East Harlem. “He definitely does try to lead by example,” said Lisi.

It was during the reign of Commissioner Ben Ward, the city’s first black commissioner, that Kelly came to public notice following the so-called Stun Gun Scandal in Queens’ 106th Precinct when it was revealed that cops used stun guns on suspected drug dealers in the mid-1980s. “Kelly was the guy the Commissioner selected to go in there and clean it up,” said Lisi.

“He’s very much hands-on, roll up your sleeves and lead by example,” said Travis, who first encountered Kelly while serving as a police attorney in the wake of the stun gun scandal. “He doesn’t tolerate any nonsense.”

Ward later tapped Kelly to run the Office of Management, Analysis and Planning, which became his launching pad for advancement and gave him his first exposure to the crime statistics that eventually became one of his biggest weapons in taking back the streets.

When Dinkins became mayor, he appointed Kelly first deputy under Lee Brown. With the New York Post running its famous “Dave Do Something” headline at the height of the Crown Heights riot, it was Kelly who was credited with finally quelling the violence after three days. When Brown resigned in 1992, Dinkins appointed Kelly commissioner.

While advancing through the ranks, Kelly built bridges that pay off to this day. Hc was constantly visiting minority groups, trying to reach out, encouraging blacks and Hispanics to join the department. In fact, his ties to that community were so solid that New York magazine once said he should be known as the city’s third black Police Commissioner.

While the force was once an Irish enclave, today Kelly boasts that it is 23 percent Hispanic and he’d like to see it even more diverse.

Kelly’s brown eyes seem to be always looking, hunting, watching. He’ll smile at times, and his brother Donald insists he always had a great sense of humor. But he doesn’t laugh the full belly laugh of an Irish man in a public saloon. He professes to enjoy a good pint of Guinness, but few have seen him imbibe.

For Ray Kelly, a laugh is usually more like a quick chuckle, a wry observation or a witty aside that might not be too out of place in a foxhole – or in a stakeout.

“I knew that Ray was always a special package,” says Donald. “As a kid, he was good in the classroom and good on the streets in stickball. And he always had a gang of friends.

“He loved the street,” said Donald, a self-proclaimed police buff. “You can’t outsmart him and you can’t scare him.”

If anything, the stakes are higher now that Kelly is “Mr. Inside” on the front line in the war on terror.

“We are doing everything that a municipality can do to prevent another attack,” says Kelly. “We have devoted thousands of police officers to protecting our city from terrorism. At the same time, we haven’t taken our eye off the crime fight ball.

“Crime is down twenty percent in the last four years,” he says. “No one, certainly not the media, would have reasonably predicted that in the last few months of 2001.”

Kelly would like to drive it even lower.

Last month, he opened a new $11 million hi-tech Real Time Crime Center, which he hopes can speed information processing and spot potential hot spots almost as they’re developing.

“In many ways we’re still a classic big organization that doesn’t know what it knows,” he said.

And he also has about twenty police officers stationed overseas in world hot spots from London to the Middle East to keep eyes and ears out for New York. An hour after the subway bombings in London last year, New York City detectives were on the scene and updating the NYPD on what the potential threat was to New York City.

“He’s probably done as good a job as anyone in the country or in the world in protecting us from terrorism,” said John Timoney.

Kelly was pulling in close to a half million a year as global head of corporate security at Bear Stearns in 2001 when he traded it in for a second run as the commissioner earning $165,000 a year.

“I always tell him you could walk away and make millions tomorrow,” attorney Hayes said. “He tells me, Tm Irish. There are some things that are more important to me than money.”

The attacks on 9/11 played a big role in getting Kelly to return.

His home in Battery Park is right across the street from the World Trade Center site. A few weeks after the attacks, when he and his wife Veronica were allowed briefly back into their apartment to collect their belongings, the devastation of the neighborhood fully struck home. “It affected me very personally,” said Kelly. And the lifetime public servant wanted back in some way. “I felt I wanted to do something and that I had something to offer.” said Kelly, “but ultimately what made me return was when Mayor Bloomberg asked me.”

Kelly and Bloomberg have as good a rapport as any mayor and commissioner in history. It stands in sharp contrast to the combative relationship between Rudy Giuliani and his first colorful crime-busting Police Commissioner. William Bratton. now the head of the Los Angeles Police Department.

Other than that brief stop on Wall Street, Kelly, now 64 years old. has spent his life in the public sector.

He attended Manhattan College and the Marine Corps Officer Candidate School, and then enrolled in the first Police Academy Cadet Program, graduating at the top of his class in 1963. Five days on the job, his Marine unit was called up and he found himself in “Nam.” When he returned to New York, he walked the beat and went to St. John’s Law School at night. He also earned a doctorate from New York University Graduate School of Law and then, for good measure, another one from the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University.

He first served as Police Commissioner during the final two years of the David Dinkins administration in 1992 to 1994, when runaway crime fueled by the crack epidemic first began taking a dip.

In between his two runs as Police Commissioner. Kelly learned to elbow his way through the Washington bureaucracy, serving as the head of U.S. Customs, and at the U.S. Treasury as Under secretary for Enforcement, where he supervised the Bureau of Alcohol. Tobacco and Firearms. He also served on the executive committee and was elected president for the Americas of Interpol, the international police organization. Kelly was also brought in to set up an interim police force in Haiti and try to end the entrenched human rights abuses as director of the International Police Monitors.

Kelly grew up in a New York that was far more Irish than the city is today.

Many of the Presentation nuns who taught him at St. Gregory’s on West 90th Street between Columbus and Amsterdam Avenues came directly from Ireland, and Irish saloons with names such as The Old Mick lined the streets of the neighborhood. Kelly was not what one would term “uber Irish.” with the gregariousness associated with the Irish politician. But he does have a rooting interest in the underdog, and insights into the struggles of the working class that were forged by the Irish culture that he grew up with on the streets around him. The bars wouldn’t open until after the last Mass on Sunday. There were no summer trips “home.” no Irish step dance or Gaelic lessons. In those days, when someone left Ireland, they rarely went back. A getaway was a summer vacation on Long Island. And that was where Ray Kelly, met his wife Veronica. “I was a lifeguard and she was a swimmer.” recalls Kelly. “She’s terrific,” he says, flashing a smile.

The apartment where the four Kelly brothers and sister Mary grew up on the corner of 91st Street and Columbus Avenue was certainly an Irish household. But brother Donald recalls Italian. Polish and Jewish neighbors in the building.

“The neighborhood had clearly an Irish feel to it.” Ray Kelly recalls.

There was also the rough-and-tumble side, and by the early 1950s, the neighborhood saw the first jarring influx of the next wave of immigrants from Puerto Rico and the rise of the city’s first serious youth street gangs. “It turned into a classic West Side Story with the influx of the Puerto Ricans and the gangs.” said Kelly. When he was thirteen years old. Kelly’s father had had enough, and decided to move the family to Sunnyside, Queens, which in those days was almost akin to moving to the suburbs. From there it was off to Archbishop Malloy High School.

All four of Kelly’s grandparents were born in Ireland; the Kelly side hailed from Roscommon. His grandmother Bridget Leonard and grandfather Patrick Kelly had both come over in 1884. It turned out they had both been on board the same boat, the Sythia. but they didn’t meet until after they landed. On his maternal grandparents’ side, Bernard O’Brien hailed from Longford and Mary Carolan came from Cavan.

Kelly’s parents were American-born. James Francis Kelly grew up in Hell’s Kitchen on Manhattan’s West Side, and his mom. Elizabeth O’Brien. was raised in the Kips Bay area in the East Thirties. Both were teeming neighborhoods of blue-collar workers in those days.

Kelly himself didn’t venture “back” to Ireland until lie was an adult, and then it was as a paid speaker to Dublin and Belfast.

His own family includes two sons. Gregory and James. Ray asked both to take the police test. They didn’t, but Ray doesn’t seem too upset that they headed off on their own careers. Greg’s a White House correspondent for Fox News and Jim is a managing director at Bear Stearns.

Ray says he’d like to go back to visit the West of Ireland when he gets some time off. That, of course, is virtually never. His last real vacation was “sometime in 2001.” Despite the constant demands, being commissioner is a job he clearly loves. He even turned down Bill Clinton’s offer to head the FBI in order to stay as Police Commissioner during his first stint under Mayor Dinkins.

Like most veteran cops, he is stoic about the tragedies that come with the job.

While this story was being researched. Eric Hernandez, a cop who had been beaten at a White Castle restaurant in the Bronx and then inadvertently shot by a fellow officer who mistook him for a perpetrator, was fighting for his life. Kelly didn’t mention it during an interview at One Police Plaza, where he works behind a desk once used by Teddy Roosevelt, but he had been a near daily visitor to the bedside of the comatose cop. But the heroic efforts to save Hernandez’s life proved futile. He died on February 8. the fifth cop to die since November 2005.

“The toughest part of the job is visiting an officer who has been shot or injured or telling a family that a loved one has died.” Ray Kelly said.

Budget constraints have forced Kelly to wrestle with a declining number of officers on the force in his tenure – down 12 percent to 37.000 officers. And he blasted an arbitration ruling that cut the pay of the new class of rookie cops by $15,000 a year.

“It’s disgraceful.” Kelly says of the new starting salary.

“The class we hired last June, the starting salary was $40.000. This class, it is $25.000.” By contrast, he said the starting salary in Los Angeles is $50,000. “Nobody joins the NYPD to get rich, but you have to give them something to live on.”

Kelly is a constant fixture on the evening news and in the papers and is widely seen as the second most powerful man in City Hall.

There are some who are starting to whisper that Kelly should try to move up a notch and make a move for Gracie Mansion himself when Bloomberg’s second term expires in four years.

It’s not the first time he’s heard the question and in typical Kelly low-key style, he bats it away. “This is the job I want and this is the job I am focusing all my energies on.” he says.

“I also don’t think I have the makeup for an elected position.” he says. “I’ve been in executive positions for a good portion of my adult life – making decisions, not necessarily compromising and making deals. And I think that’s a good part of being in an elected office.”

Is he going to stay for the full four years of Bloomberg’s second term? “I hope so.” he answers. And after that? “I never plan that far ahead.” he says.

The best part of the job? “It’s being in a position to see all the great work that goes on every day. I’d like to be able to personally commend every cop for the great job they do.”

And with that, New York’s top cop was off, dashing to another press conference and a swearing-in ceremony for new undercover officers.

“It’s very rare to find a man with his mental capacity as well as his physical and mental toughness.” said attorney Eddie Hayes. “He’s a very good example of the warrior intellect, and we’re fortunate to have him as our general.” ♦

Leave a Reply