April 13, 2006. Beckett’s 100th birthday. In anticipation of that April, April future of Aprils past, I recall the first time I ever met him, Beckett, on now into a second decade, the man with the baggy greatcoat, the grey-shocked hair and the yellowed packs of Dutch cigars, sitting by himself in the lobby of the Hotel PLM-Saint Jacques, reading a copy of an Irish newspaper. It all began with his first note, which read:

Dear Mr. Axelrod,

Sunday next 14th, 11 a.m.

Hotel PLM-Saint Jacques,

17 Boulevard Saint Jacques,

Paris 14.

Yours,

Samuel Beckett

After days and weeks and months and years, full access had now been granted and, once again, the thought began to disturb me. What does one say to Samuel Beckett? Where does one begin? “Seen Godot recently?” “How’s your endgame?” “Read much Joyce?” The importance of those opening lines, those words, of how to begin, had been preying on me for almost four years, ever since the idea benudged me to attempt a meeting with the man. At first thought, the possibility seemed absurd at best, absurd at least, since who actually visits a man who embraces privacy the way Verlaine embraced absinthe or Proust his madeleine? Who actually speaks to a man who has discovered that disinterest is the best response to criticism and indifference the best response to solicitation. Who actually sees a man who, upon learning of his Nobel Laureate, fled to Tunisia in order to avoid both the onslaught of flashing bulbs and the cacophony of reporters’ catechisms? No one. Generally.

I had learned about Beckett’s penchant for seclusion through a good friend of his, the Irish poet Brian Coffey, with whom I had corresponded while attending Oxford in 1978. Coffey affirmed all that I had thought or read or read and thought about concerning Beckett’s apparent self-isolation, of his need to be alone. It was no contrivance. I logged Coffey’s observations and his intimate knowledge of the man somewhere in my right hemisphere in case an occasion would arise in which it might be, in some small measure, beneficial; and, in the summer of 1981, such an opportunity arose.

In July I was notified by the Camargo Foundation, a foundation for artists and French scholars established by the late Jerome Hill, that I had been granted a writing fellowship which would allow me to write at their estate in the south of France during the winter of 1982. It was then that I retrieved the idea of contacting Samuel Beckett. So, with no shibboleth at hand other than Brian Coffey’s name and Brian Coffey’s insights, I composed a letter to Mr. Beckett indicating that, yes, I would be in Paris the following January, that, yes, I had talked to Brian Coffey, that, yes, I understood why he harbored his privacy and I appreciated that, but if he would be so kind as to grant me an interview, I would be very appreciative. My letter was contrived within the parameters of modest literary standards, with minimal allusions to anything noteworthy in the field of belles lettres, and to fall without any excursions into the realm of experimental prose since, I thought, there is no need to play the role. I did feel that, odds aside, I had absolutely no chance of an audience and that the letter, should it ever have reached Mr. Beckett through the editorial circumnavigations of his publisher, would have been promptly discarded as simply another invasion or intrusion or infestation of, into, of the man’s time.

Several weeks later, I received a response:

Dear Mr. Axelrod,

Thank you for your letter of July 23. If for an “interview,” no. Privately, by all means. If I am in Paris at the time.

Sincerely,

Samuel Beckett

The response seemed Beckettian enough…no, yes, maybe; however, paradoxes aside, now it was too late. That is, he accepted my invitation to the dance, and I had nothing to wear. Absolutely nothing. What does one say to Samuel Beckett? But I still had five months to survey my wardrobe and find appropriate garb.

The months passed quickly. Prior to my leaving for Paris I had written Mr. Beckett indicating my day of arrival and my length of stay before my subsequent departure for Marseille. I had hoped that my letter would have reached him in time for a response, but nothing had arrived before I left the States; however, when I arrived at my hotel, there was another note awaiting me:

Dear Mr. Axelrod,

Thank you for your letter. January 16 not possible for me. Hope we may meet later in the year. With all fond wishes.

Yours sincerely,

Samuel Beckett

A reprieve. I had more time. More time to think of something pithy, witty, self-assured, something that wouldn’t reveal me as being a literary poseur or, worse, a terminal graduate student counseled in the archives of items-not-to-say. I left for the Cote D’Azur.

In mid-March I had returned to Paris. I had informed Mr. Beckett of my return plans, my length of stay, and the days which would be most convenient to meet; and, in a follow-up letter of unusual honesty, deprived of any fiction, I wrote:

Dear Mr. Beckett,

I am looking forward to our meeting, however, I am rather apprehensive. By nature, I am shy and do not want to be intrusive. My words and letters are generally humorous and effusive since, as you are well aware, the saddest people on this earth are, most often, the clowns.

Regards,

Mark Axelrod

When I arrived at my hotel, I was surprised to find no response awaiting. I tried to contact an acquaintance in Paris who was acting as an intermediary, but could not get in touch with him. Suddenly, I found myself in a state of accelerated anxiety, since I didn’t know whether Mr. Beckett had written me or not and if he had, had he stated a time to meet which I could not or stated a time to meet which I could but, not knowing, could not, or stated a time to meet which I could, would I be able to contact him and tell him so?

On the following day, when I finally reached my friend, he said, yes, I had received a letter, but, no, he didn’t have it with him since he was at his office and it was at his home. So, I had to wait until later that afternoon in order to secure its contents. Needless to say, I worried the entire afternoon that, due to circumstances out of my hands, in others’, I had stood up Samuel Beckett. That somewhere in or near or out of Paris, Samuel Beckett had given me his time and I had, quite simply, rejected it. The thought made me feel queasy, sullied, as if I had declined a gift which someone had gone to painful lengths to paint by hand. When I finally found out the contents of the letter they alleviated my fears, but, at the same time, precipitated the anxiety that was to follow, since I began to have second thoughts about the meeting. I had hoped, in some foolish way, some self-defeating way, that he would have written:

Dear Mr. Axelrod,

Paris too cold. Have left for holiday. Sincere regrets.

Warmly,

Samuel Beckett

Which would have enabled me to breathe freely my own regrets and extinguish my personal misgivings; however, such was not his response, and I was left without an aide to assist me. What does one say to Samuel Beckett?

On the morning of 14 March I awoke prematurely at 7:30, but, then again, I may not have slept at all. I had my usual Parisian breakfast: café crème, a croissant, a half-baguette with cherry jam and, that morning, the seventh chapter of Gogol’s Dead Souls. I was hoping I could glean an irony or two from the Master which I could parlay into a beautifully contrived witticism of my own; however, chapter seven held no answers.

After finishing my petit petit dejeuner, I slipped on my jacket, turned up the collar, and wrapped my scarf around my neck before heading for the Metro stop Denfert-Rocherau via Chatelet and Montparnasse-Bienvenue. Preoccupied as I was with recalling the lines and pages from Murphy to Company, I, of course, took the wrong train; but having left two hours early, I had planned for such a gaffe, and since no one aboard that underground quiescence knew where I was going or how nervous I actually was, the blunder became a measure of my nostalgia.

As the Metro clacked its way from one port to another, among the solace of those flickering tunnels, all I could think of, in rhythm to the meter of the iron on the tracks, was: what does one say to Samuel Beckett? The line even crowded my mind in French. Nine months had expired and I was still stumped for an answer; then, for no apparent reason, at the stop Chevaleret, I began to think of our correspondence. Each letter I had received was equally as short as or shorter than the one before it, which seemed to be an attempt at creating something which took as long to read as write; which seemed to be no different than his own work; which seemed to be a reflection of a moribund perception that there was no time to write anything much longer; which seemed to depress me to think that, in time, and time and time alone, his words were marked in time, marked time, and time was much too short in time.

When the Metro stopped at Nationale, the thought came to me that my visitation was not decided upon unilaterally. That is, it was not my decision alone. That at any time in our correspondence he could have written:

Dear Mr. Axelrod,

Thank you for your interest, but I only meet with good writers.

Sincerely,

Samuel Beckett

I would have understood. I would have known the reason. I would not have been hurt. Much. So why would he be interested in meeting me, just another wordsmith? Could it have been, as one friend so suggested, that since his first novel was allegedly refused by 42 publishers and mine was holding even at an even 18 that, perhaps, he would suggest a few more names to significantly extend the agenda of rejection. I politely smiled at the suggestion.

At the Place D’Italie, I decided to get off the Metro and walk to our meeting place. The morning was cloudless, warm for Paris in March, quiet. Turning a corner, I noticed on the opposite side of the Metro tracks, Beckett’s place of choice. The PLM-Saint Jacques struck me as an odd place to meet: concrete and glass, brass and custom carpeting, loud walls, loud languages. My initial feeling was that Beckett could not have lived there, though, perhaps, he did. He didn’t say he didn’t, he didn’t say he did. Perhaps he wanted to meet there in order not to direct me to his home, if, in fact, it were not his home. If it were an uncompromised meeting place, a place he only frequented, a place unlike his own, then it was only a further indication of the lengths to which the man would go in order to protect the sanctity of his space.

I nursed a café crème from 10:00 to 10:55 thinking from the top of the cup to the bottom of it about my opening lines, of how our talk would unfold, of the questions to be asked and answered; then, I walked to the registration desk, cleared my throat and asked, “Le chambre de Monsieur Beckett, s’il vous plait,” and the words, rattling from lips in the most insipid of French accents, were answered with “There is no Samuel Beckett here.” At first, I thought it was another bit of irony. A Beckettian maneuver of being there and not being there. I quickly abandoned the notion. “There must be some mistake,” I asked, but the computer told no lies. At that time, or shortly thereafter, it struck me that Beckett must have meant what he said. How odd. To mean what one says. No symbols where none intended. To meet there, read the note, to meet. Any assumptions on my part were purely fictional.

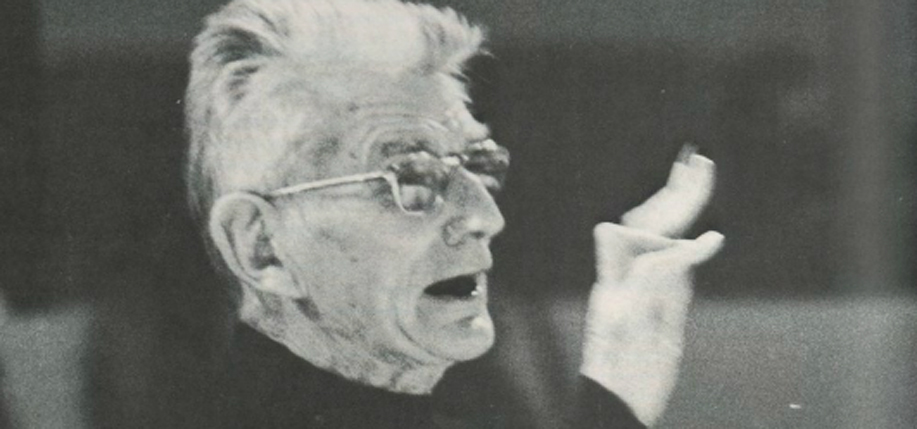

Excusing myself for the error, I glanced at the clock which read 11:03, then turned and looked over my shoulder. Sitting in a corner of the lobby, at the base of a concrete pillar of no notable distinction, wearing a trench coat with fur collar and crew neck burgundy sweater, sat Samuel Beckett. Throughout that crowded lobby, cramped with parables in foreign tongues and faces stained with oddly shaped cheekbones, Beckett’s presence seemed much louder than the words around him, yet, he sat alone: cropped shock of silver hair, pointed ears, creases in his cheeks. No one else noticed.

I adjusted my shoulder bag, cleared my throat once again, and walked up to him. Looking down, I held out my hand. “Mister Beckett,” I said, with only a partial fibrillation to the voice within my chest. Looking up from his London paper, through spectacles fashioned with squinteyed lenses, he extended a hand crippled at several joints and answered in a voice dulcet with the odd mélange of French and Irish accents, “Mister Axelrod. Shall we have a coffee?” “By all means,” I replied, looking into a pair of soft blue eyes. And all I planned to say or thought I should was suddenly forgotten. Lost within the confines of some remembrance of things past.

For the next hour or so we chatted about nothing in particular, everything in general, nothing in general, and everything in particular. It was clear to me after no more than fifteen minutes that all the preconceived notions I had had or had heard of Samuel Beckett were fictional accounts of my own, or others. Confabulated prose poems. That as we talked, I saw or felt, what seemed to me, a profound sadness in his eyes. But Samuel Beckett was not without humor: the wrinkles at the corners of his eyes attested to that, as did the accent of a childlike pucker on his left cheek which pronounced itself each time one of us said something worthy of the grin.

About his work he said very little, about himself he said little more, other than he considered himself a “last ditch writer” who knew that he was unable to be a teacher or a scholar or a pedant of modern stuff, and were it not for writing, he was uncertain as to what his life would have been. Or why. I suggested that things seemed to have worked out for him. He grinned. His eyes shifted from mine to the table, as his arthritic fingers toyed with a plastic lighter. No, he said, he hadn’t read his biography nor was he interested in doing so, didn’t want one written, but there was “no copyright on Samuel Beckett’s life,” though, he hesitated, his friends were not too pleased with it. Too dramatic, they said. Yes, he said, and the writer of the book now had her nails in Simone De Beauvoir. Yes, he was returning to some older writings. Fiction, I said. Is that what you call them, he answered with a tobacco-stained smile, just prose, was all he added, then looked again at the lighter.

I wasn’t sure which of us was the more nervous. He, the Master, or I, the apprentice. What I did feel, after the coffee was served and cooled, was that I knew him by not knowing anything at all, by recognizing that he avoided talking about himself, by observing that his countenance was gentle and demure. Our conversation was like a chess match: I attempted to maneuver him to speak about himself, he attempted to maneuver me not to, guarding himself from checkmate. He, declaring his life to be uninteresting, and I, knowing fully well that I had nothing of much substance to offer, moved ourselves, like pawns, back and forth, side to side, seeking to know something of the other, while revealing nothing of ourselves, and only resting in between brief periods of silence which were barely broken by my erratic breathing or our choreographed sips of café noir. Café au lait. He asked me about my writing, what I was working on, how I could work on two novels at one time and sketch a third. His eyes widened when I said I would just attenuate one sense and augment another. He put a finger to his lips. I felt as if I had impressed him, but the thought quickly vanished. Another fiction of my own. I asked if he’d care to read anything of mine. He said, certainly, but not too long, he added, he couldn’t read very well because of the damage that cataracts had done to his eyes. I changed the topic. He doesn’t travel much, only once to America, has given up directing, and, no, has never seen his plays performed. He couldn’t tolerate the pain. Proust, yes, Baudelaire, yes, 19th century French fiction, we liked them both, both liked it. He talked of the Second World War, its isolation, betrayals within the Resistance, Vichy France, a novel he wrote called Watt which kept him sane for three years and which some people thought very funny, funny enough to become the core of my own dissertation.

Eventually, the conversation turned, as each one must, turn and turn again, whether intentionally or not, to Joyce, on Joyce, of Joyce, upon whose name he only raised one eyebrow and reached for another of his small Hollandse Stokjes. In that look, that simple motion, I think he said all he ever wanted to say about the man. I understood and did not pursue it, since there were other topics to discuss. When he finally looked at the table and fidgeted with his glasses, I knew it was time for him to leave. He had to see to something else. Groceries perhaps. I initiated the closure by saying that I didn’t want to take any more of his time, and after he paid for our coffees we walked outside and shook hands: this self-effacing master of the word and me.

Standing face to face we agreed to meet again, perhaps another winter, perhaps a spring. In Paris. Instinctively, I put one hand upon his shoulder, shook his hand again, and told him to take care of himself in much the same way I say it to my father. He smiled, then, after wishing me a safe trip home, he walked away. As I started in the opposite direction, I felt an unmitigated urge to crush someone or something, but I didn’t know who or what. In retrospect, maybe it was my arrogance I was after, my conceit or self-adulation, my high regard for the words I write. My hubris. Then again, maybe it was a personification of death I wanted. Something palpable, around whose throat I could stretch my fingers and with one deft and simple snap, break its immortal neck.

As I turned, I saw him walking down the street, moving from the sunlight into the shadows and back again. With his hands stuffed into his pockets, the shock of hair bristling in the wind as distinguishable to me as the ceaseless arms of winter around the chest of spring; his tall, narrow frame walked briskly down the Boulevard Saint Jacques, turned a corner and disappeared. What does one say to Samuel Beckett? One needs to say nothing, I thought, one only needs to feel him. In that there is all that’s meant to be said and all in that is nothing left to say.

I had met with Beckett and I had the fortune to meet with him again. And I had cor-responded with him for several years up until the time he was put into a home, a home that not so gently arrested both him and his voice. And after that, nothing. But I shall always cherish that first meeting, a meeting of the arrogance of passing youth, pleading with the graces of aged humility for the ageless answers to the written word. ♦

Leave a Reply