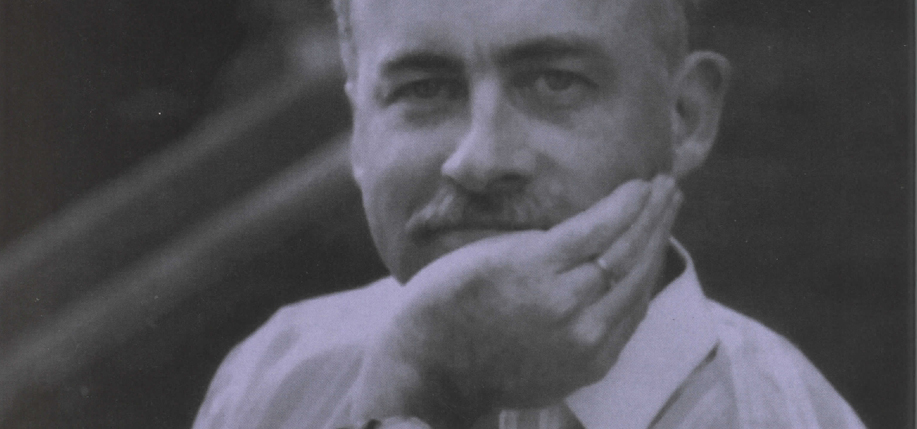

Peter Quinn wanted to do something simple.

It was 1994 and Quinn had just published Banished Children of Eve, his epic novel of New York City and the Irish famine. Up until then, there had been a monumental gap in American literature. The Irish had been in New York City going back to the days when Peter Minuit, as legend has it, hoodwinked the local Algonquins and snatched up the island of Manhattan for 24 bucks in trinkets.

And yet, despite this massive Irish presence, there had never been an iconic Irish novel of New York City. Chicago had its James T. Farrell, Boston had its Edwin O’Connor. True, there were many brilliant New York Irish writers. But it seemed there never was going to be a New York Studs Lonigan trilogy, or a New York equivalent of O’Connor’s The Last Hurrah.

More disappointing still was the fact that the famine had apparently exacted such a toll on the New York Irish that it was always hard to find writings from the era, the actual words of survivors. So traumatized, it seemed, were these banished children that survival was all that mattered. Putting pencil to paper and recounting this experience was just too painful, and would be for decades.

Then along came Peter Quinn. Banished Children of Eve, which won an American Book Award, gave a voice to those traumatized immigrants. In fact, Quinn created an entire chorus, a fictional and historical symphony of a city which loathed the Irish yet absorbed them, forever transforming both the city and those immigrants.

Meanwhile, almost a decade before Martin Scorsese and Leonardo DiCaprio had everyone talking about the New York City Draft Riots with their film Gangs of New York, Banished Children of Eve shed important light on these tragic events, which everyone seemed to want to forget. (Quinn, in fact, was an adviser to Scorsese on Gangs of New York.)

What must be added is that Banished Children of Eve was a big book. Not just because it took on big themes and big ideas. No, it was also, literally, big, weighing in at well over 600 pages, meaning Quinn had to put in years of research in order to accurately depict New York during the middle of the 19th century.

When all the research was done, his book written and accolades accepted, Quinn was sure of one thing when it came to writing his second book: He wanted to keep it simple.

“I love Raymond Chandler,” he said during a recent interview, referring to the famed noir author of such detective classics as The Big Sleep and The Long Goodbye.

“So I said, let me try something fast. I’ll try a detective thing. I’ll set it in New York City instead of L.A.”

Nearly a decade later, Quinn is back with his “detective thing” entitled Hour of the Cat. The novel splits time between Berlin and New York, and explores the frightening eugenics movement on the eve of Adolph Hitler’s mad quest for global domination.

Is this Peter Quinn’s idea of a “fast thing”?

The 58-year-old author laughs, then says: “What I really wanted to be in life was a historian. I love the research. There’s no better excuse to not actually write.”

Quinn continues: “In having written two novels now, I’ve come to see that part of the process is getting totally lost sometimes. You go down alleyways, some don’t pan out, some lead you to other places.”

Part murder-mystery, part historical warning, Hour of the Cat has already received rave reviews. Entertainment Weekly called it “a tingling thriller,” while USA Today called it “the best kind of historical novel, driven by memorable characters, a suspenseful plot and real-life issues.”

Raymond Chandler had his beloved private eye Philip Marlowe. Quinn has Irish-American Fintan Dunne.

We first meet Dunne as he is investigating what Quinn calls “a simple New York City homicide” in 1938.

But like the reader, Dunne will soon learn that this killing has its roots in Nazi Germany, where Hitler’s designs on the world may or may not be thwarted by a secret coup being planned by a cadre of German military officers.

Quinn journeys the reader halfway around the world to introduce us to Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, an actual historical figure who indeed opposed Hitler.

The Berlin setting of Hour of the Cat also allows Quinn to introduce one of the book’s central ideas: the eugenics movement, which was popular in both Europe and North America.

According to Quinn, Hour of the Cat had its roots in the once fashionable notion that the Irish were genetically inferior.

“I had some questions left over after Banished Children of Eve,” says Quinn, a Bronx native who now lives in Hastings-on-Hudson with his wife Kathleen and his teenaged children Genevieve and Daniel.

Quinn adds that 19th century scientists believed that you could tell the intelligence level of people by the size of their skulls. Many believed the Irish had abnormally large skulls, and thus, were genetically less intelligent than many other ethnic groups.

By the 1930s, of course, the Nazis had turned genetics into a justification for mass murder.

But the uncomfortable fact about Hour of the Cat is that it shows eugenics had powerful supporters in the U.S. as well.

While researching Hour of the Cat, Quinn published a shocking article in American Heritage about the eugenics movement in America.

“By the beginning of the twentieth century, several forces had joined together to give the eugenics movement new power and prominence,” Quinn wrote.

“By the 1890s a large — and, to many old-stock Americans, alarming — wave of foreigners was arriving. Between 1898 and 1907, annual immigration more than quintupled, from 225,000 to 1,300,000, and its primary source was no longer Northern Europe but Italians, Slavs, and Jews from southern and eastern Europe.”

Quinn continues: “It wasn’t long before the presumptions of eugenics about the unfit and the growing threat they posed began to find their way into law. With the enthusiastic endorsement of President Theodore Roosevelt, a true believer in the threat posed by `weaker stocks,’ Congress voted in 1903 to bar the entry of persons with any history of epilepsy or insanity.”

Forced sterilization became a popular way to prevent “defective” humans from reproducing. Ultimately, Quinn says that 60,000 Americans were sterilized under the guise of being genetically weak.

The ideas Quinn explores in Hour of the Cat are not locked away in the past. He sees echoes of it in the 21st century scientific quest for genetic information.

“People are always looking for a gene to explain human conduct and human intelligence,” Quinn says.

Peter Quinn was born and raised in the Bronx, and attended Bronx schools from kindergarten to high school. His grandparents were Irish immigrants who fled the famine and its aftereffects.

“The Quinns came from near Holy Cross, in Tipperary, in the 1870s,” says Quinn. There are also Mannings and Purcells in his family tree “who arrived in 1847 from — we think — Kilkenny.”

Quinn continues: “My mother’s mother, Catherine Riordan, was from Blarney. Her father, Seamus Murphy, was from outside Macroom, also in Cork. I went back with my mother to his village in the late 1970’s. The priest said that 200 of the 300 families in the town had Murphy as a last name, so unless we knew my grandfather’s grandfather’s first name, it would be hard to trace our line. Things can get complicated in the Irish countryside.”

The household in which Quinn grew up emphasized education. Quinn’s parents (Peter and Viola nee Murphy) were both first-generation college graduates.

“School was a big deal,” Quinn recalls. “So was storytelling. Both my novels are stuffed with tales, facts and lore gleaned from a lifetime in New York.”

Quinn’s dad worked as an engineer but attended law school at night, eventually going into politics where he was elected a congressman and later became a judge.

“We worshipped FDR, and we thought the second coming was when Kennedy was elected president,” said Quinn of his loyal Irish Democratic family.

Quinn graduated from Manhattan College in 1969 with a degree in history, then went to Kansas City, where he worked as a teacher. He thought about moving even further west, to California. But being out of the Bronx for the first time in his life made him look back at his hometown with a different set of eyes.

Specifically, he wondered about his immigrant grandparents. He’d known a lot about the place where they and so many others settled — New York and America.

What he knew little about — because few people ever seemed to talk about it — was the place they came from: famine-scarred Ireland.

Quinn returned home, taught at Paramus Catholic High School and eventually received a master’s degree in history from Fordham and completed all the work for a Ph.D. other than the dissertation.

Quinn never thought about following his dad into politics.

“The Bronx was changing,” Quinn notes. “I grew up at a time when old immigrants were leaving. This was literally a crumbling world.”

More historically than politically inclined, Quinn nevertheless did follow his father in one way. Quinn became a political speechwriter, eventually working for New York’s last Irish-American governor Hugh Carey, as well as Governor Mario Cuomo.

Quinn helped write Cuomo’s famous 1984 speech at Notre Dame, considered a landmark document on how Roman Catholics could remain close to their faith in the political arena.

The grind of politics, however, soon wore Quinn down.

He signed on with media conglomerate Time Inc. as chief speechwriter in 1985. Quinn then began something of a double life as a writer and commentator on Irish America.

Quinn, along with his brother Tom, wrote a 1987 TV documentary McSorley’s New York, which won a New York-area Emmy award for “Outstanding Historical Programming.”

Quinn also served as editor of The Recorder: The Journal of the American Irish Historical Society and also contributed articles and reviews to American Heritage, The Catholic Historical Review, The Los Angeles Times, The New York Times and The Philadelphia Inquirer.

Quinn first went to Ireland in the late 1960s.

“I was shocked at how poor the country seemed. I remember O’Connell Street at rush hour being filled with bicycles, and bad food, and shoddy goods in the department stores. It felt to me like an Eastern European country. Still, I fell instantly in love with the place.”

His last visit was in 1998 with Frank McCourt, during the filming of Angela’s Ashes.

“`All had changed, changed utterly,'” he says quoting Yeats. “Ireland was a modern, booming part of the EU.”

Following Banished Children of Eve, Quinn also became a prominent talking head for acclaimed documentaries such as The Irish in America and New York: A Documentary Film.

Quinn is still at the company now known as Time Warner, serving as corporate editorial director. He plans to retire this year, which he says will allow more time for writing.

Next up for Quinn is a collection of his essays to be published by Notre Dame University Press. The tentative title is Looking for Jimmy: Reflections of a Bronx Irish Catholic.

Then, Quinn plans to write what he is calling a “family memoir,” which will look back at the lives and times of his parents, and would also explore the Great Depression, the murder of one of his uncles and even the infamous disappearance of Tammany Hall loyalist Judge Joseph Crater, which was back in the headlines recently.

In the end, it’s not surprising Quinn would turn his historian’s eye on his own family. For all of the rich history and grand scope of his trans-Atlantic novels, it was from his Bronx parents that Quinn learned a simple, powerful, particularly Irish lesson.

“Words were what mattered in my house,” he says. “As well as a talented songwriter, my father was a terrific storyteller, both in public forums and at the family dinner table. My mother told my brother and me, `There’s nothing worth doing in life if it doesn’t leave you with a good story.'” ♦

Leave a Reply