Kennedy was a rich man’s son, a Harvard man. But when he campaigned in the Bronx, all they saw was one of their own.

Back in 1960, when it seemed that the cute Irish guy might actually make it to the White House, my Irish immigrant parents were almost too superstitious to talk about the idea. Never big on assimilation, they still referred to Ireland as home, even though they had lived in New York for more than 30 years.

If John F. Kennedy became president, we kids wondered, would our parents, relatives, neighbors, all those greenhorns and people “from home” finally feel like real Americans?

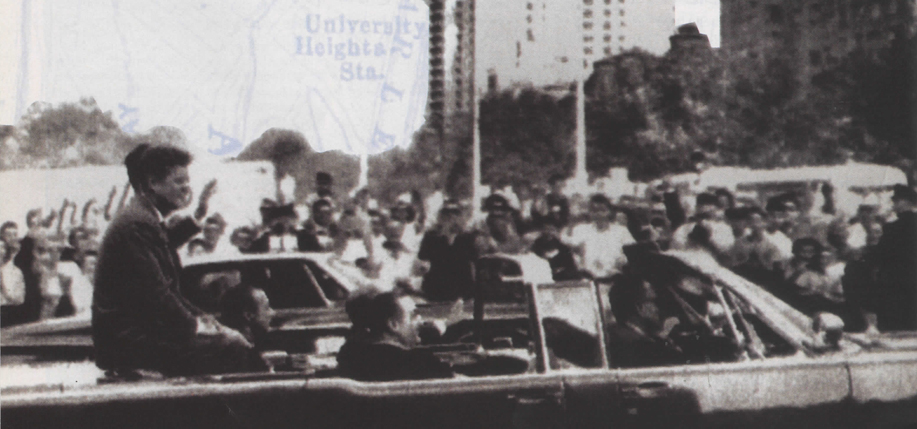

He made his last campaign swing through New York on Nov. 5, three days before the election, and I went with my sister and some neighborhood kids to Fordham Road and the Grand Concourse to watch his motorcade pass by. Kennedy appeared sometime after 12:30 p.m., seated on top of an open convertible and looking more like a conquering hero than a candidate for office.

Seeing the diverse, hyphenated crowd, along with signs like “The Home of the Knishes Think Jack Is Delicious,” we realized that this candidate resonated not just with Irish Catholics but with every minority group.

These adoring Bronxites didn’t see his father’s money, Harvard, or the Court of St. James’s; in their eyes, Kennedy was a guy from the neighborhood who made good.

The crowd knew only that he wasn’t a Protestant and wasn’t a Mason and that his great-grandparents “had come over on the boat.” He didn’t have a WASPy first name like Woodrow or Grover or Millard. At the time, he seemed shockingly ethnic.

The afternoon Kennedy’s motorcade paused outside the Loew’s Paradise Theater; he parted the Grand Concourse much as Charlton Heston had parted the Red Sea inside the theater a few years earlier.

His triumphant procession did have elements of farce; people fainted, women rushed out of beauty parlors with towels over their wet hair, and doctors, their stethoscopes swinging from their necks, left their patients just to catch a glimpse of him.

Confetti was everywhere. Teenage girls screamed and did manic jumping jacks to see the candidate over the heads of the crowd. Another Jack, a goofy bicyclist named Jack Fleishman, escorted the motorcade, weaving in and out between Kennedy’s car and his police escort.

While these people were not the type to use the word “charisma,” they were under Kennedy’s spell and they knew it; they saluted him even after he passed by. All I can remember is the color of his hair — copper — and being awed that someone with a full head of hair, unlike Ike, might actually be elected president.

Kennedy finally arrived at the Concourse Plaza Hotel, Babe Ruth’s former hangout, and in his speech, he described himself as “the candidate from the Bronx,” a reference to his childhood years in Riverdale. This remark was enough to make some less refined Bronx boys overthrow the barricades, upended a press table, and force the police to call in reinforcements.

The candidate then headed out to Queens, but not before stopping his motorcade and jumping out to offer congratulations to a Bronx bride he had spotted in the crowd. After he left, the rain that had been threatening all afternoon began to fall.

Forty-two years after Kennedy’s assassination, it’s hard to remember what an enormous issue Kennedy’s religion was 45 years ago.

That September, 150 Protestant leaders led by Norman Vincent Peale had publicly opposed his candidacy, charging that Kennedy’s Catholicism made him, like Khrushchev, the “captive of a system.” Nor were these ministers alone in their paranoia; a large segment of the American public believed that Kennedy intended to move the pope into the Oval Office and force every American to attend Sunday Mass.

When we went to bed the night of the election, the outcome was still undecided.

“It will take a miracle for him to win,” sighed my mother, never an optimist.

When she woke us the next morning with the words “He won,” she sounded as if she didn’t quite believe it herself.

Kennedy’s victory seemed more unreal when I got to school. At St. John’s Grammar School, at Kingsbridge Avenue and 232nd Street, even the crabbiest nuns, their flushed faces poking out of their habits, couldn’t stop smiling, convinced that their prayers had won the election for the man whose tiny mother went to Mass daily.

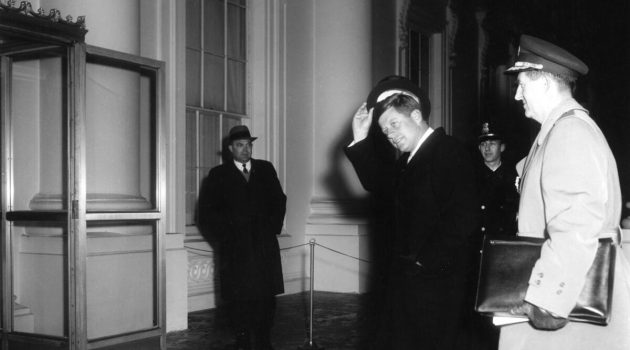

The day of Kennedy’s inauguration was a succession of extraordinary events. The morning weekday Mass, usually the province of a smattering of biddies, was packed, despite a snowstorm the night before.

My father, a bartender who labored through Christmases, Thanksgivings, and the births of his children, took off from work the day the first Irish Catholic president was inaugurated.

Both my parents, usually so quiet and reserved, gushed as they watched the proceedings on television. My mother, a dental assistant, noted the new president’s “beautiful teeth.” My father, who always wore a hat, was thrilled that the new president went hatless.

“The cold doesn’t bother him a bit,” he exclaimed.

My sisters and I couldn’t stop staring at Jackie, who carried a muff and wore the most adorable fur-trimmed boots. Like the rest of our neighbors, except for those who had a problem with “the drink,” my parents had alcohol only when company came for dinner. They hardly ever drank when it was just the two of them, and never in the daytime. So it was something of a shock to me when they both had highballs after Kennedy was sworn in, toasting each other with their customary “good luck.” That one afternoon, they felt very American.

When a wake is held, it is customary to give out prayer cards for the deceased. On the tragic weekend of Kennedy’s death, the company that makes these cards, a Brooklyn business called Abigal Press, did something it had never done before: it manufactured thousands of J.F.K. prayer cards and distributed them to funeral homes around the five boroughs.

That weekend, mourners went to their local funeral parlor, took a J.F.K. card, and said a prayer for the slain president, almost as if his wake were being held in one of the nearby rooms. ♦

This article originally appeared in the December / January 2006 issue of Irish America.

My parents brought me along to see then Senator Kennedy on this same day. I would love to contact the writer of this piece to find out more about the day as my parents are both dead and I was just a young boy at the time. Was the photograph used with the article from the Bronx campaign event on the 5th Nov ?