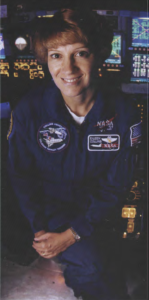

For Eileen Collins, outer space means a chance to really see the world. Back home after a fourteen-day mission to the International Space Station, Collins and her husband Pat Youngs talk to Georgina Brennan about their love of Ireland, their children and the future of space travel.

Eileen Collins presses her face against the glass of the shuttle. She is desperately trying to see something. Like anyone far from home when they see land, they look for what they know. Except for Eileen Collins, 48, far from home in outer space. And that little slice of familiarity is a country she visited once but thinks of often. “I was trying to see Ireland. But our orbit was too low and it was too cloudy,” she laments, sitting on her hands in an uncomfortable chair in the Sheraton Hotel and Towers in Manhattan. She admits being pleased to talk to Irish America; after all, her father James, a retired postal worker, has been a subscriber to the magazine for all of its twenty years.

Collins, the calm commander of the shuttle Discovery — the first mission into space since the Columbia disaster two and a half years ago — is enduring a grueling round of media interviews. A sort of public debriefing. “It was very important that we got back into space. We will fly into space until we finish what we have to do,” she says. “I believe we need to keep on exploring. We’re just taking baby steps with the space shuttle and the space station. We’re going to go back to the moon. It’s part of this country’s plan to get people back to the moon, and to Mars. We’re going to get out there and find out. I do believe that. I think it’s kind of unimaginable that we would really be alone in this universe. I think that probably not our generation, but future generations of people on Earth will find intelligent life.”

Thanks to a completed mission, NASA has confidence that the space program is not dead. Discovery returned safely to Earth on August 19, fourteen days after launching on a beautiful Cape Canaveral day. Commander Collins staged a flawless nighttime touchdown of STS-114 at Edwards Air Force Base at 5:11 a.m., and in the silence of the predawn day, nations across the globe breathed a huge sigh of relief. A big bright dot pierced the sky and a loud double boom sound announced the arrival of a job well done.

“Discovery is home,” Mission Control said as the wheels touched down on the 6,800-meter runway. “We are back,” Collins breathed into the radio. “We are back.”

After 36 days away from her pilot husband Pat Youngs and her children Bridget Marie, nine, and Luke, four, all Collins wanted to do was see her family, take a shower and grab some Mexican food. “I don’t take my family for granted,” she smiled.

Collins, an attractive redhead with coffee-colored eyes, who marked this flight as her fifth into space (twice serving as commander), has spent the last four years training for Discovery. As the warmest woman, anybody could ever meet, it’s hard to imagine that the regimen is easy for her. Asked if because she spends so much time away from home, she loves her family twice as much as anyone else, she smiles. Her eyes water a little and she whispers, “I miss them all the time.”

On August 19, Collins and her teammates — Irish-American pilots Jim Kelly and Steve Robinson, New Yorker mission specialist Charles Camaroa, Australian mission specialist Andrew Thomas, and Japanese mission specialist Soichi Noguchi — felt the first flushes of gravity in the Mojave Desert. After successfully re-supplying the International Space Station and testing new in-orbit inspection and repair techniques, the “Irish crew,” as they called themselves, were home. “We were joking around and we made Soichi an honorary Irishman,” Collins told Irish America. Her pilot Jim Kelly said they called the team the Irish crew because both he and Collins share Irish heritage with Robinson, so it seemed appropriate to do what all Irish people the world over do, give someone else the joy of being Irish. Collins, known on the crew as Mom, traces her Irish heritage on both sides to the Collins clan from Cork and the Reidys from Clare. Somehow her father James’ rail worker ancestors and those of her mother Rose Marie engineered a meeting in the railroad town of Elmira, New York, so that future national hero Collins could be born in 1956. “I love Ireland, I definitely want to go there again. My father’s mother, Marie Reidy, told me as much as she could remember about Ireland, and I wrote it all down.” Collins was in Ireland once with Youngs at a golf tournament. She told Irish America in 2000 that while there, she and Youngs tried to look up her Collins relatives in the phone book, but found so many that they gave up. Youngs, who met Collins in 1983 when they were both stationed at Travis Air Force Base in California flying C-141 cargo transport planes, married the woman he calls his hero in 1988.

Now a pilot with Delta Airlines and an avid golfer, Youngs gets to Ireland about as frequently as his wife gets to Space. “I have golfed all over Ireland, Portrush up in Northern Ireland is a favorite. I’ve never really been down in the Southeast, but next time if I get a long layover maybe I can visit that part of Ireland,” Youngs told Irish America. On the promise of the lush golf courses of Mount Juliet in County Kilkenny, Mount Wolsley in County Carlow, and Kilkea in County Kildare, Youngs could barely contain his excitement. “I love it there, I just got back from a trip there with seven guys; we played at the Bushmills Malt Causeway Coast Amateur Golf Tournament in County Antrim. We usually fly into Shannon or Dublin and get to see all the country in between,” he said pulling at his Causeway 2005 polo shirt. Youngs, a handsome, tanned man, has dancing blue eyes when he talks about Ireland. His mother Mary Kelly’s family came from Waterford. “I never got to look them up, but I think they might have disowned us,” he joked. “But I did discover while talking to Jim Kelly that his mother and my mother had the same name.”

He says it has been hard for the whole family to get to Ireland but they are going to try to visit soon. Now that Collins is back on Earth, anything is possible. “It’s good to be on the back side of this thing,” joked Youngs. During the mission, his children offered prayers every night. “Even my four-year-old is really good at his prayers. When he would offer his intentions he offered them for the mission and for the people who at that time were under threat of a hurricane. He is a conscientious little boy. My daughter is old enough to know the risks, but we prayed and they came home.”

Youngs was in Florida when Discovery came home, having traveled from Houston, where he and Collins raise their children. Psychologically, everyone feared the worst once Discovery was in space. NASA’s comeback kid, Discovery flew after the Challenger disaster in 1998 and now again after the Columbia tragedy. Because Columbia went up okay but disintegrated coming home, Discovery’s re-entry was NASA’s greatest concern.

On February 1, 2003, the Columbia shuttle burst into flames after heated gases broke through its heat shield. The seven-member crew was 16 minutes from home. The tragedy was blamed on insulation foam that fell off and damaged the orbiter’s left wing upon take-off.

When Discovery launched on July 26, the entire world held its breath when a piece of foam peeled off the fuel tank. The similarity to what had happened to Columbia before it burst into flames was not lost on anyone. It not only raised questions about the safety of future shuttle flights but also called into question the competence and engineering judgment of NASA. NASA administrator Dr. Michael Griffin admitted, “Well, certainly we were lucky.” Luck of the Irish, Jim Kelly would say; the result of hard work, Collins would offer. NASA said the debris caused no significant damage and gave the green light for landing after the mission was complete, despite a tear on the cockpit’s thermal blanket. Collins knew then that though the crew had enough supplies to take shelter on the International Space Station, there would be no need because she was coming home in her own shuttle.

“I was never worried [about Discovery coming home]; the whole country was praying for us. And my crew had a great sense of humor,” explained Collins, who keeps her grandmother’s Connemara rosary beads close by. Collins told CNN that while in space she knew she had a job to do, and that was all that mattered. “I have never had any pressure from my family to not fly this mission. My parents, my husband, my children, my friends, you know. Having said that, I asked myself many times, do I really want to fly this mission? And the answer always came back yes,” she said.

Once in space, Discovery had a tremendous amount of work to do. “We were very busy,” she admits. Very busy wowing NASA observers. Collins engineered a fantastic first for NASA with a breathtaking in-orbit maneuver. On flight day three, Collins guided Discovery through the first ever “rendezvous pitch maneuver” as the orbiter approached the International Space Station for docking. In layman’s terms, that’s an astonishing slow-motion backflip that had never been done before. One longtime observer of NASA said, “Big boys, move over, Eileen Collins has just done it.”

Collins said she didn’t do it for the thrill or the accolades. She did it because it had to be done. “We exposed the underside of the shuttle to the space station crew members. John Phillips and Sergei Krikalev took pictures of our tiles, and that helped us ensure that we had a good healthy underside to come home with.”

This Discovery mission was designed to test changes made to the shuttle since the Columbia disaster, including improvements that were meant to prevent foam from breaking off upon launch. During the mission, Robinson conducted an unprecedented spacewalk under the shuttle to extract two protruding pieces of fiber that risked overheating during re-entry. Robinson and Noguchi also tested repair techniques adopted after the Columbia tragedy and replaced one of four gyroscopes that keep the International Space Station in its orbital position. The crew also delivered 12 tons of equipment to the Russians and the Americans aboard the space station and retrieved waste to clear out space in the cramped orbiting lab. Discovery was one of the most photographed shuttles in space exploration history. Because of Collins and the bravery of her crew, some of those photographs were awe-inspiring.

NASA said the huge amount of data collected during the “return to flight” mission would help them figure out how to make the shuttle a safer craft.

“We had a lot to do, and sometimes we had to go to Plan C, and sometimes we were really off the map,” Jim Kelly told Irish America. “But Eileen was always willing to listen to ideas. I am a typical Irishman, I get hotheaded. Eileen is not like that. She was always calm, and that made us a great team.” The mission initially had been scheduled to last 12 days, but an extra day was added so the crew could transfer as much material and provisions as possible to the space station because of uncertainty over the date of the next shuttle flight. On top of that, low clouds impaired visibility at Kennedy Space Center, causing a further 24 hours of downtime for the crew. “We had an extra day where we had nothing to do, so we were just hanging out, looking out of the windows, joking around. It was nice to be able to do that with such a great team,” Collins said. “I like floating in space. I like looking back at Earth, at places I’d like to travel to someday. We flew right through the Aurora Australis, the Southern Lights over Australia. It was so beautiful, just winding around like that candy I can’t think of the name of. At first, it is white and then yellow and green. You can see the pictures, but pictures don’t do it justice. It was very mysterious looking.”

Collins said that during the mission there was a threat of a solar event. “That can threaten a mission because radiation from the sun can break through metal. You would not continually expose yourself to x-rays except for medical reasons, because too much can cause cancer and other problems. We would have been told to take shelter near big containers of water, but the radiation was not high enough to pose any danger.” Collins said this kind of danger to humans in space is just one area NASA wants to explore. “Because you are floating around, your heart gets weak, your muscles get lazy. On Earth, we are constantly working against gravity, so our muscles are working out, and our hearts are working out. In space that does not happen. You start losing calcium and those kinds of things. We need to explore countermeasures for them. We want to travel to Mars, which can mean six months to a year in space; we need to find ways to enable humans to stay there that long. We have the International Space Station where astronauts are constantly trying to research the human body, for long periods of space travel.”

America is about to announce the launch of the Crew Exploration Vehicle to fly people back to the moon. While Collins explains the future of American space exploration, she hasn’t decided anything about her own future yet. But she admits to Irish America that it is somebody else’s turn to fly. “I think astronauts who have not flown should go over me who has been there five times,” she says.

Collins is always honest about her feelings. It is, as her crew says, what makes her a great leader, and a woman anyone would be proud to know. She sometimes gets into trouble for what she thinks, but she is never shy about speaking her thoughts in her matter-of-fact way. “I have been accused of being an ‘environmentalist from space,’ but I just call out to Houston what I see. I try not to force my opinions on the environment. If you study maps you can pick out countries. The best thing for an astronaut is to study previous pictures of Earth from space. The Earth changes, the cities are gray and they grow bigger; rivers, a dark blue color, change course. Jungles, dark green, and tropical forests are getting limited. Deforestation is taking place in South America and you can see land use changing. I saw fires in Central Africa and they were flaming, so I called Houston.” But Collins’ descriptions are of an Earth that humans are losing, or destroying. Perhaps space exploration will stop that if more astronauts get to fly and get to see the Earth changing. “As a country, I think we would be better off having more astronauts who have experience in space,” she says about the future of the space program.

Now, with the future of the space program taken care of, Collins, who paid her own way through college and saved money to get flying lessons that brought her to the Air Force and eventually to NASA, has her children’s future to concentrate on.

“I do not spoil them. I was brought up with discipline and it worked for me. That is how I parent, and I love them and I miss them when I am not around them,” she admits as her husband and a NASA publicity manager approach us. Collins grew up in a government housing project, the second of four children. Her parents split when she was nine, and the family went on food stamps for a while until her mother got a clerical job at the correctional facility in Elmira, NY.

“I wasn’t there for my children much and I couldn’t contribute much in the way of money, but I paid for them to go to Catholic School because it was the right thing to do,” her father James, a Rochester resident, told Irish America in 2000. Recently, he told the Star Gazette in Elmira that he was always proud of his daughter. “She is a wonderful, wonderful mother,” he said. Her mother Rose, who raised her in Elmira, watched the landing from her home with her friends Jean Hurley, Marge Tierney, and Debra Burke. She admitted it was great to have her daughter home, for her, Pat Youngs, and the children.

Although Collins has moved on to another interviewer, her eyes say she does not want to finish chatting about Ireland and the things she loves. But she is still on a mission: to inspire the world to believe in space exploration. But her husband, still eager for conversation, sneaks over to me for a chat. “I remember the last time I met the folks at Irish America. We had a lovely dinner at the Plaza, Eileen and I really enjoyed it. She has a tough job, but her toughest job is putting up with me,” he laughs as he recalls the Irish-Americans of the Century Gala where Collins was an honorée. As she watches him from her chair, she smiles and he winks at her. “You know, it was our 18th anniversary while she was in space. She never sent me a card! But I’m just glad to have her home.”

While Collins is busy catching up on watching Luke make flying noises with his toy planes and Bridget practicing the dancing she loves so much, Discovery, which will retire in 2010, will go into space again, but this time without her. The shuttle, which has a number of missions to complete in order to fulfill the objectives of the American side of the International Space Station’s mission, is scheduled to launch again in March. That mission, STS-121 (to be piloted by Irish-American Mark Kelly), will continue to test new equipment and procedures that increase the safety of space shuttles and deliver more supplies and cargo for future International Space Station expansion.

Discovery will bring a third crewmember to the station, European Space Agency astronaut Thomas Reiter. Without Discovery to ferry equipment to the Station after the Columbia accident, only two people could be supported onboard until the necessary provisions were in place. That would hinder space exploration and the chance for humans to get higher and deeper into space. Because of Collins’ mission, this can now happen.

“The shuttle has been a step along the road to allowing humans to access space, but it did not reach that goal. We need to keep at it. We are giving ourselves what we hope is plenty of time to evaluate where we are,” said NASA administrator Michael Griffin. “We don’t see the tasks remaining before us being as difficult as the path behind us.” ♦

Editors note: On December 16, 2022, Eileen Collins, a member of Irish America’s Hall of Fame was awarded the Wright Brothers Memorial Trophy by the National Aeronautical Association for her perseverance in the advancement of aviation and aerospace as a teacher, astronaut, and leader, and for serving as an inspiration for all those seeking to break barriers in their field.

Leave a Reply