Seamus Heaney was awarded the 1995 Nobel Prize in Literature “for works of lyrical beauty and ethical depth, which exalt everyday miracles and the living past.” The first person from Northern Ireland to be so honored, Heaney was born on April 13, 1939, the eldest of nine children, to Margaret and Patrick Heaney, at the family farm in Mossbawn, County Derry.

In his Nobel Prize acceptance speech, he spoke of “poetry’s power to do the thing which always is and always will be to poetry’s credit: the power to persuade that vulnerable part of our consciousness of its rightness in spite of the evidence of wrongness all around it, the power to remind us that we are hunters and gatherers of values, that our very solitudes and distresses are creditable, in so far as they, too, are an earnest of our veritable human being.”

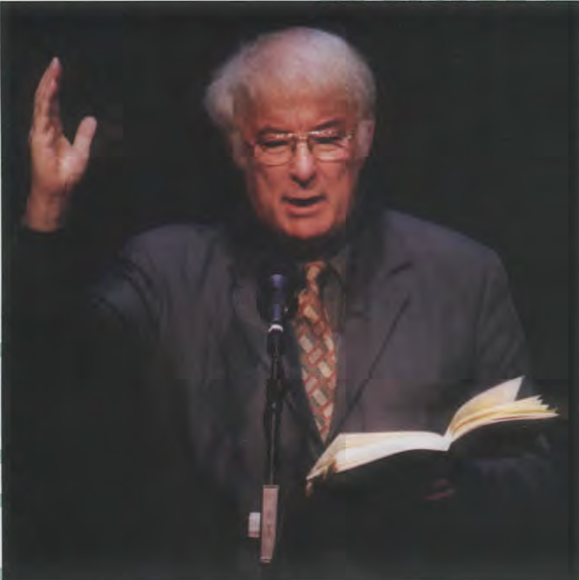

Patricia Harty spoke to him in New York on the occasion of his birthday, April 13, 1996. His book Spirit Level had just been published.

What does it mean to call yourself a poet?

I think if you call yourself a poet it means that you live by it, so to speak, and for it, in a very serious way. There’s a phrase of Ted Hughes which I like very much. He said that the true poem emerges from the place of ultimate suffering and decision in us, and I think if you call yourself a poet, you publicly consecrate yourself to living somehow by the places of suffering and decision.

How does it feel to have the world reflect back at you that yes, indeed, you are a poet?

I think the discipline which writers must perfect is the discipline of doubting the world, the discipline of self-knowledge and self-castigation. Certainly the activity should induce a sense of vigilance — it’s a kind of spiritual exaction to he a writer. But the answer is that I accept the recognition in good faith.

Can you tell me about your mother?

My mother was very strong — very unrufflable, steady on the emotional keel. Righteous and majestic and vulnerable. Her McCann family were terrific, they had the volubility of protest, and they were democrats.

My father had a different kind of majesty, the country farmer’s silence and hauteur. My mother had an unbending thing which she shared with women of that generation, a child a year in eight, nine, 10 years. The giving-birth factor involved, I suppose, a willful adherence to the compensations of Catholicism — the cult of the suffering mother of Jesus, the cult of the suffering Jesus, and the cult of St. Anne, the mother of Mary. These were actual real psychic resources for sublimation in the lives of women. In particular for ones who were going through, without much consolation or understanding, the solitude and exhaustion of childbirth and child-rearing and the biological entrapment of being in a place with no birth control.

Nowadays I remember that affirmative bold outcry of prayers from women in church as a cry of rage and defiance. My mother wouldn’t have put it that way — she would have seen it as a form of transport and endurance.

Are you a disciplined writer?

I’m not very disciplined, no. I’m half disciplined. I’m not a person who gets up every morning at the same time and sits at a desk and plunges into it. Prose writers have to do that. On the other hand, the older I get the more I feel that you should peg out a pitch and provide space for the game to be played, mark out a landing place for the muse if she wants to come down. So time, time alone, when the pages are in front of you, or you’re reading, time is what’s important. In the beginning, I used to say to myself anything that’s worthwhile forces its way through. And to some extent that’s true ♦

Patricia Harty’s full interview, Seamus Heaney Winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature originally appeared in the May/June 1996 issue of Irish America.

Leave a Reply