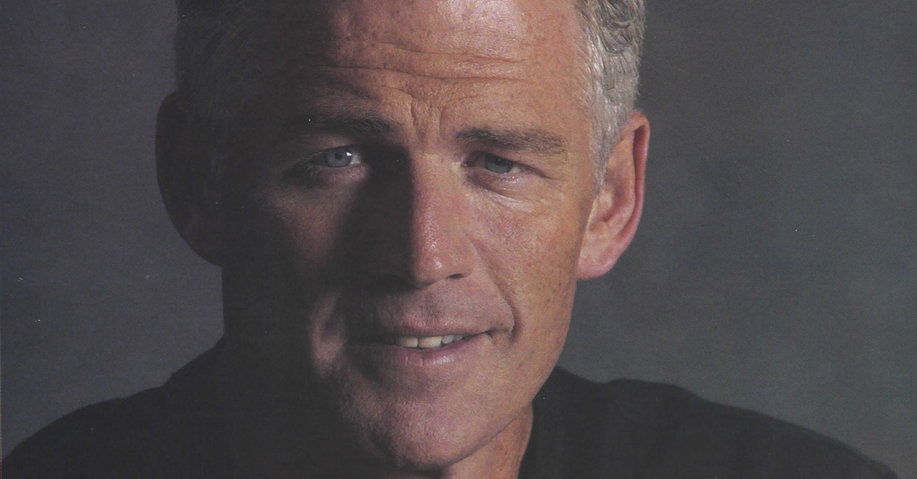

On the corner of 34th and Broadway the crowds of tourists and harried workers tried to look the other way. But it was hard to ignore the tall tanned handsome man in the crisp white shirt with the gray hair — even in New York, where every day a million handsome men pass along the crowded streets.

“Hiya,” he says, his face splitting in half, his arms swooping me up in a hug.

It’s downright hard not to fall in love with Tom Westman. Ask any one of the millions of viewers of Survivor: Palau who watched as for six weeks Westman, 41, a firefighter from Sayville, New York towered over every other contestant — a god amongst men.

“Tom 108” as they called him because of his T-shirt. A lieutenant for Ladder Company 108 in Brooklyn, Westman became a household name across America making this Survivor, the tenth in the series a breakout hit for CBS.

And now he is one hot property. His face graces a special edition of TV Guide, along with Brad Pitt, Tom Cruise and Housewives plumber, James Denton. He had paparazzi following his every move for weeks after the finale of the show aired in May.

Not bad for a graduate of Archbishop Molloy High School in Queens, New York who only wanted to grow up to be a Guinness taster.

On this hot afternoon, Guinness is firmly on Westman’s mind as we go in search of a decent pint. “My friend Jim Feeney and I did our backpacking tour of Ireland and England in search of the best pint,” he laughs. “When they asked me at the airport what the purpose of my visit was, I told them I was looking for a good pint of Guinness. The guy said it was as good a reason as any,” Westman throws his head back and laughs as he strides along Broadway. He has a huge laugh, one of those Irish laughs that precedes a great story.

“Any Blarney Stone or Rock near here buddy?” he asks a deliveryman, who knows who is asking him the question but is too cool to let on. He points us towards 7th Avenue. As we walk away I hear him telling someone “that’s the shark slayer guy from Survivor.”

Westman can’t quite grasp the full measure of his fame.

“I keep expecting someone to tell me to get out of first class, to put the bathrobes back. I was in Las Vegas doing a promotion and you know you don’t belong there when you are taking pictures of the bathroom,” he laughs.

Still trying to come to terms with winning a million dollars, Westman says his life has utterly changed. “CBS is great, they gave me the chance to have a midlife crisis on their dime and they have been superb since the win helping me out. But if I’m having a hard time getting my head around it, and my kids are definitely not sure what’s going on. They are getting to stay up late, there’s more people calling to the house. It’s exciting and it’s disruptive.”

Westman is Irish on both sides, a fact that was a bit of an inside joke among the Survivor cameramen. “Being a fair haired Irishman, every morning I slathered on the sun block. I have too many memories of being burned by the sun when I was younger to take a chance. So for two hours they couldn’t film me because I was white with cream. I just sat there and let it sink in,” he smiles.

James Varley, Westman’s maternal grandfather, came to America from the quiet Galway village of Clonbur in 1916. Determined to become an American and join the police force, he went for his citizenship interview only to be told he would have to wait a month. “He told the judge he couldn’t wait, because if he did he would be too late to apply for the police force. So the judge gave it to him there and then,” he explains.

“He was quite the storyteller, a great guy, the quintessential Irishman, but he only ever wanted to be an American, it was all about being American,” Westman says, recalling his grandfather. “It was my mother who tuned into the family’s Irish background and passed it on to me.”

His father side is also Irish. But the family’s origins are different than most.

The Westman Islands south of Iceland take takes their name from a group of Irish captured and forced into slavery by the Norse. They became known as the Westmen because they came from the west. The descendants of these slaves who returned to Ireland passed the name down through the generations.

“When I was in Ireland I saw there were more Westmans in the phonebook in Dublin than in New York, but my family comes from Waterford where my father’s grandfather was born,” he laughs.

The only boy in a family of four girls, Westman grew up steeped in Irish culture. His mother chased her four daughters to Irish step dancing classes that were held in a local pub. Westman escaped because Irish dance was something boys in Queens didn’t do back then. “I was surrounded by Irish stuff growing up,” he says. “Middle Village was Irish, Italian, and German immigrants and second-generation. It was a neighborhood where big families were the norm and neighbors looked out for each other’s kids.

“I went to Saint Margaret’s grammar school and our yard was everyone else’s. Stepping out the back door put you in the middle of a game of Red Rover, Johnny on a Pony, Giant Steps, or whatever the game of the week was.” Westman spent his summers building forts, having battles, climbing trees, and playing tag. When he grew up a little, he looked to Ireland for adventure and stories.

“I studied Irish history and I loved it. My imagination was inflamed by the stories of the 1916 Rising and the civil war.”

Westman went on to study history for three years at the State University of New York in Binghamton and is currently finishing up his degree at Queens College. “I love history, especially Irish history. It was never an effort on my part to immerse myself in all things Irish,” he adds. “I love the new Irish culture. I love Black 47. I’m a huge fan of Larry Kirwin (Black 47’s lead). I love his slant, his irreverent treatment of “Danny Boy.” I love being exposed to differing views.”

After spending a summer in Mayo with Feeney’s relations, Westman returned to New York. Seeing that the job as Guinness taster was not in the cards, he took a look at his options.

His father was a fireman, and soon Westman would stand beside him.

“I saw how much my father loved his job and I loved that. I wanted that job. In 1985, I joined the Fire Department and I even served with my dad until he retired in 1987.

“When I was a kid the hero image hooked me, but as I got older I saw how much time off my dad had, how he was always there for important events and that also made me want the job.”

Westman loves his job. Even with fame knocking on his door as America began to tune into his adventures on primetime, he vowed to remain a fireman. But now as he approaches his 20 years service mark, which makes him eligible for retirement, Westman says his wife’s voice is getting stronger in his ear.

Westman met his wife Bernadette through his youngest sister, Erin. At the time, Bernadette, a nurse, whose family hails from Leitrim, was working for an accounting firm. She was looking for a date for the firm’s Christmas party. “My sister said to her, `If the tickets are paid for and there’s free drink, Tom will go.’

“I was not looking to settle down when I met Bernadette. I was enjoying a life of great fun and little responsibility,” Westman admits. “She jokes that she knew I would spook easily, so she gently set the hook and I didn’t know I was caught until I was being hauled onto the boat,” he laughs, adding, “But it’s a boat I’m happy to be aboard. That has been the great story of my life.”

Now Bernadette wants her husband home more often, safe more often. Come August, Westman may be hanging his uniform up for the last time. “It will be hard to find something I love as much as the Fire Department,” he says.

Because of Survivor, Westman is sought after as a motivational speaker, and offered product endorsements, but he didn’t go onto Survivor to quit the Fire Department, he did it for his children — the prize money is mostly in a college fund for Meghan, 9, Declan, 7 and Conor, 5.

He also went on Survivor because Westman cannot live a day without challenging himself.

“That’s what I love about my job. It’s the challenge. Every day is not heroics, every day is not fighting fires — sometimes it’s about getting someone out of an elevator. It’s that day to day thing, that makes me love it,” he says.

“When I was cast on the show, the producers asked us to wear something I would normally wear to work for a photo shoot. I told the producers I did not want to wear my uniform. They agreed but insisted on the T-shirt.” The producers also told him to wear black dress shoes. “I threw them away in the jungle and put on a pair of sneakers I had hidden,” Westman laughs. “My wife told me not to get caught on the island without a bathing suit, so I wore a bathing suit as underwear. They couldn’t make me wear what I didn’t have and you need every advantage out there. You needed sneakers to go fishing in the water. It was about survival.”

In a game where outlasting and out-playing are tools of the trade, Westman quickly towered over the other contestants. He led his tribe to win every single immunity challenge decimating the opposing tribe, made up of mostly Alabama men, down to one. He kept three sand dollars close by, one for each of his children, and tapped them before each challenge.

He claims he initially wanted to just go and play the game and keep under the radar, hang onto his gray hair and look non-threatening. But unfortunately for the other contestants, he is a trained fireman. “Had I had 19 other NYC firemen against me, I would have had a lot more trouble,” he laughs.

As he hauled a footlocker across the ocean floor he thought of each child and their futures. “The challenge for me was to get one full pull for each child.” He thanked his fire training for his ability not to panic under pressure.

When the tribes merged, he again ruled. “I am really proud that I was one of the instruments of team building in those early games. As a lieutenant in the fire department, that is what I do; I have younger people whom I guide. I don’t hold their hands or swing the ax for them. I train them and give them confidence and encouragement, and they step up to the plate.

For one reason or another, mainly to do with food, Westman became a real hero on the island when he killed a shark with a machete. “I watched the sharks every day. We were so hungry it became about getting dinner. That day I watched ten or twelve of them as they swam in a school close to shore. I raced up the beach and swung the machete into one. My brain just disconnected from my body. I held it by its tail; afraid it would eat a large hole in my stomach. Then I threw it onto the beach and I raced out of the water. We were starving and we ate until we were sick,” he says. “When we were sitting around the fire somebody said, `did anyone ever do this on Survivor before?’ And Gregg said, `Nobody did this anywhere before.’ I have a friend who goes shark fishing all the time, and it is killing him that his friend who doesn’t fish will always be known as the shark slayer,” he laughs.

Finally, Westman’s strength and determination saw him hang onto a pole for half a day to beat out dolphin trainer Ian and advertising executive Katie for the million dollars and a new car, a Chevrolet SSR.

“I was always about getting to the final two, the others were about not being voted off. I was looking to get respect at the end to win.” And win he did, he even came out of it with five new buddies he often calls.

“We are a real rat pack, the final six. Sometimes I will think of something that only they will have the answer to, so its fun having that,” he says.

Though Survivor filmed Westman the hero, it is not a word he would use for himself. It is a word he uses to describe his children and the tireless workers at the charitable organizations he is involved with.

“My daughter Megban contracted pneumococal meningitis at 18 months and was left profoundly deaf. She pressed buttons, shook rattles, and pulled strings, and thought that the toys were broken because she heard no sound. That broke our hearts. It seemed at the time that all our dreams for our daughter were lost.”

Time was critical and decisions needed to be made, and the Westmans early research into deafness was not encouraging. “We received conflicting information. But we found out about a device called a cochlear implant. It is surgically implanted behind the ear and has an external unit, which contains a microphone and processor to translate sound into electrical impulses that stimulate the auditory nerve.

“Meghan was implanted at the age of 20 months. She has been mainstreamed in our own school district since kindergarten, and is now thriving in the third grade. Seven years later, she has not missed one grade,” Westman says proudly.

Westman became involved with the Alexander Graham Bell Association for the Deaf and Bard of Hearing because they promote early intervention. Also because of Meghan, in 2001, he found himself involved with Disabled Sports USA, an association who provide sports rehabilitation programs to anyone with a permanent physical disability. He volunteers as an instructor where he helps introduce recently disabled soldiers to adaptive skiing.

“I never want another parent to miss out on a chance for a full life. Meghan is so assertive now, she is a self-advocate and her life journey is just beginning. She is an extraordinary young girl and her possibilities are limitless,” he says.

And thanks to Survivor, Westman’s own possibilities and dreams are also limitless. And he did it without causing rancor.

“I knew that the show was going to be watched by my children, and I knew they were going to judge me on how I played and whatever reputation I carded out of the experience was going to be based on whether I was underhanded or just downright evil. I couldn’t do that.”

So he did what every man does. He listened to his wife.

“My wife said, `just be yourself out there, you have good social skills, you are athletic and strong. Play it as yourself and people will like you.’

“That was good advice.” ♦

Leave a Reply