Two hundred years ago, the city of Washington was just over ten years old and, quite frankly, a mess. One visitor reported that it was little more than a boggy marsh dotted by tree-stumps, with rutted tracks linking half-finished buildings and randomly placed dwellings.

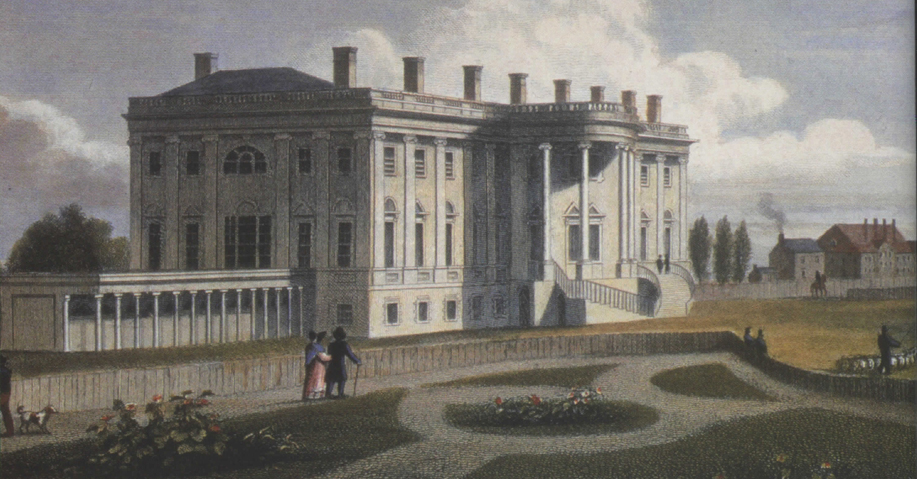

Thomas Jefferson was the occupant of the one prominent building that looked in any way completed. This was The President’s House, built on a site popularly known as Pearse’s Farm.

America’s third president was living the lonely life of a widower in what was then the largest residence in all of America, although only half of its 31 rooms were in regular use.

Like George Washington, who had envisioned the house but never lived there, Jefferson had his own ideas on architecture. Jefferson’s father was a professional surveyor and the young Virginian had been exposed to architectural influences from an early age.

Like Washington’s Mount Vernon, Jefferson’s Monticello was the result of its owner’s obsessive attention to architectural detail, as relayed through John Neilson, the Antrim-born builder who led a team of Irish craftsmen at Charlottesville.

Despite their best efforts, however, the pedestrian business of building facilities for legislators, administrators and the executive in the less sylvan setting of the new federal capital had not gone well for the great men, even though there were less than 300 persons in total to be accommodated.

As they had conceived it, the District of Columbia would represent the best in contemporary thinking on urban planning and public architecture.

Nothing like it had ever been attempted before anywhere in the world.

Jefferson and Washington agonized over the scale and symbolism of the two principal buildings in the new Federal City — The President’s House and The Capitol. Jefferson felt so strongly on the matter that he later submitted an anonymous entry for a President’s House design competition that he himself had recommended. But Washington was happy to be influenced by L’Enfant, the French soldier who was the de facto “designer-in-residence” to the infant republic.

Having produced an impressive master plan for the new capital, L’Enfant was dithering about the detailed designs of the principal buildings. When he did talk about them, the expansive and elegant images he conjured were a little frightening, even for devotees of French palaces like Jefferson. Eventually George Washington agreed that L’Enfant had to go, and Jefferson’s competition suggestion was accepted.

In fact, there might have been no need for a competition at all if the first president’s memory had been a little better. Traveling through the southern U.S. in 1791, he had heard of an Irish designer-builder working in Charleston, South Carolina, who was reputed to be precise and practical, and who had done some impressive work on public buildings there.

On his return, Washington mentioned the man, but not seemingly his name, to the three commissioners charged with he development of the federal capital. One of the commissioners was the Irishman Daniel Carroll of the Ely O’Carrolls, who owned a substantial estate in the Maryland section of the District of Columbia that became part of the site of the new city.

A year later, faced with the task of replacing L’Enfant, the commissioners wrote to Jefferson asking him to relay the name of the Charleston genius so that they might contact him. Three weeks later Jefferson replied, perhaps disingenuously, that his inquiries had been fruitless.

The man they were seeking was a young Kilkenny-born architect and builder who had established himself in Charleston about five years previously. Encouraged by a noble patron in his native Desart, near Callan, James Hobart trained as a draughtsman at the Royal Dublin Society school. He was apprenticed to prominent Dublin architects of the time, including Thomas Ivory and Thomas Cooley, whom he assisted in the design and construction of the Royal Exchange (now Dublin City Hall) before leaving for Philadelphia about 1785.

Diffident, gifted and capable, Hoban made an immediate impression when he arrived in Charleston some two years later. There he ran a drawing school, designed some private residences and worked on two of the city’s more prominent public building projects — a 1200-seat theatre at Savage’s Green, and the refurbishment of the old colonial state house as a courthouse.

Even before Hoban’s arrival, the Irish were already prominent in the building trade in Charleston. Samuel Cardy, a Dublin builder who had fled Ireland to avoid the fall-out from some small-time corruption in the Navan Barracks project, built the Episcopal St. Michael’s Church, just across Broad Street from the colonial state-house, in 1753.

At the same junction, his son-in-law William Naylor designed and built the Charleston Guard House and later designed the Exchange building on East Bay Street nearby.

The Irish had also established themselves as merchants, land-owners and politicians in the Carolina “low country,” Many of them (Bamewells, Burkes, Lynches, Rutledges) were “signers,” lawyers and elected representatives in the emergence of the new federal republic and its constituent states.

Sir Pierce Butler, a colorful scion of a Carlow branch of the Kilkenny Ormondes, became South Carolina’s first senator, and was the owner of extensive plantations in the area. He was among the “first characters of the place” who had recommended Hoban to President Washington.

Hoban was not unaware of the potential of the new federal capital as a source of work, sending his business partner Pierce Purcell northwards with letters of recommendation from local worthies.

Hoban himself followed, bearing a letter from his fellow-Irishman, the jurist Aedanus Burke, to Daniel Carroll. Within days, George Washington was told the exciting news: the “practical builder” he had heard about in Charleston had surfaced.

President Washington wasted no time in arranging a meeting with Hoban to brief him on exactly how he imagined the house of the leader of the new republic should look. The ideas the President put forward were sensible and modest. Locked away in a Georgetown inn for an intensive twenty-day period, Hoban was able to translate the presidential concepts into a design competition entry that was almost guaranteed to succeed. And succeed it did, in the face of only token challenges from eight others (as many as four of whom may have been Irish builder-designers like Hoban himself).

The commissioners also appointed Hoban as supervisor of construction, and gave him a site on which to build a house (selling house sites in the new city was a priority for George Washington, who took an active part in the marketing). After a short argument with the President about the cost of the project, with Hoban quoting his experience on the Dublin Royal Exchange contract, the design was amended to two stories over basement rather than the original three.

Hoban took over the assembly of materials, including large consignments of stone from the Aquia quarries. He established an elaborate fabrication site where some of his skilled slaves from Charleston set up a brick making station. Irish and Scottish masons were hired to do the detailed stonework, and Hoban led them in the establishment of the First Federal Lodge of the Freemasons (the lodge continues to be active, and to revere the memory of Hoban).

It would be eight years before the President’s House was anything like livable, and then only barely. Abigail Adams, wife of a president in the last months of his first and only term when he took up residence in late 1800, famously hung her laundry to dry in the newly plastered East Room, complaining of the damp conditions everywhere.

But at least Hoban stayed on the job, and in fact was still building on the White House site some thirty years later. Continuity such as this was not the experience on the other prominent site in the new city — the U.S. Capitol.

Here a succession of architect/builders had been engaged in trying to realize the design of a gifted amateur, William Thornton. Thornton was a Scottish-trained medical doctor of Caribbean planter background who had won the separate design competition for a building to house the legislature (Hoban had also submitted an entry for the Capitol contest).

Progress on the project was so slow that Hoban was often asked to intervene. But he regarded the troublesome contract as a distraction from his main purpose and it was not until 1798 that he accepted a formal responsibility for it. To make the additional charge more palatable, he was given the title Surveyor of Public Buildings.

In that same year, another architect of Irish background made an appearance on the Federal scene. Thirty-four-year-old Benjamin Henry Latrobe was the son of a Dublin-born preacher whose French grandfather had pioneered the linen trade in the city after helping King William win the Battle of the Boyne.

Dispatched to England for pastoral training, the elder Latrobe met and married a young Philadelphia lady and moved with her and a four-year-old Benjamin to London, where he became a famed teacher and pastor in the Morarian faith.

Young Benjamin married into a prominent London clerical family, and, having trained in architectural design and engineering at the offices of Samuel Corkell and John Smeaton, set up his own professional office.

But his wife died in the birth of their third child and in consequence, he suffered a nervous breakdown and the collapse of his business.

America offered him the possibility of a new beginning, and within two years of his establishment there he had secured both his professional reputation and his personal happiness, obtaining his first commissions and marrying Mary Elizabeth Hazelhurst.

With his French background, London training and Virginia connection, Latrobe must have seemed the very model of a modern architect to Jefferson.

In the early years of the new century, Latrobe began to work on some small additions and adaptations at the presidential mansion.

Neither Jefferson nor Latrobe were reticent in giving their disparaging opinions on the building’s design. But Hobart didn’t care. By now he considered his original brief well fulfilled and had moved on to other projects (he was also involved in the design and construction of the first — and short-lived — Departments of the Treasury and War, sited on either side of the President’s House).

In all the circumstances, it came as no surprise and little disappointment when in 1803 Latrobe was given the task of completing the House of Representatives wing of the Capitol, and made Surveyor of Public Buildings.

It took Latrobe eight years to bring the Capitol project to something near conclusion. Within a further three years he and Hoban were both engaged in rebuilding their respective landmarks after the destruction of the War of 1812. In a small coincidence, the burning of the President’s House in 1814 was supervised by a Dublin-born British officer, Robert Ross. Before torching the mansion, Ross and his officers sat down to a banquet set by President Madison for forty of his own commanders, whose victory he thought was assured.

Hoban’s specification of a painted finish to cover the burn marks on the mansion’s natural stone gave it its distinctive color, and from then on it was called The White House, though this title was not made official until 1902.

During the refurbishment, President Madison decamped to the nearby Tayloe House, for whose construction Hoban had acted as “measurer” or quantity surveyor of William Thornton’s design. Today the Tayloe House, completed in 1799, is the oldest surviving private building in central Washington, and serves as a museum and exhibition center for the American Institute of Architects.

After Jefferson’s departure from office Latrobe could not sustain his early success in the public sector, despite obtaining major commissions such as the Mother Cathedral of the Catholic Church in the United States at Baltimore. He would leave Washington within a few years to settle in New Orleans, where he died of yellow fever in 1820. His daughter Lydia married her father’s best friend Nicholas Roosevelt, who became a partner in a Mississippi steamboat venture with Robert Fulton, the pioneering steam engineer. Fulton’s father was born in Callan, thus giving Latrobe a connection with the Kilkenny town too.

James Hoban meanwhile prospered. A respected member of the community, he was a member of the Washington City Council for almost 30 years. He remained a devout Catholic and a devoted husband and father, bringing up nine children with his wife Susan Sewell, whom he had married when he was 40. He built up extensive property interests while still maintaining his involvement in design and construction.

He lived on to complete the north and south porticos of The White House in the 1820s and to see his former student and apprentice, Robert Mills of Charleston, become America’s first widely recognized native-born architect. Mills went on to design the Washington Monument, which was completed a few years after his master’s death in 1831.

In 1976 a simple marker was erected near the site of Hoban’s birthplace in Desart. The house where he grew up was still standing as late as the 1940s.

Some buildings from the Desart Estate, where Hoban received his early training as a carpenter and wheelwright, also survive. Desart Court itself, rebuilt after a Civil War burning, fell into disrepair following its acquisition by the Land Commission, who divided the lands among local farmers. The house was demolished in the early 1950s.

A more recent successor in title to both Hoban and Latrobe visited Kilkenny in 2001 to view what he regards as an outstanding example of public architecture — the conversion of the tower at Kilkenny Castle to a conference center.

As Chief Architect in the Public Buildings Division of the U.S. General Services Administration, Ed Feiner supervised the award of hundreds of major contracts for public buildings to architects throughout the U.S. each year.

Like Hoban, he is affable, practical and diffident, though the scale and method of his work was slightly different from the Kilkenny man’s. The Office of the Chief Architect’s typical assignments have included 155 port-of-entry stations for the U.S. Immigration Service, a replacement for the Murrah Federal Building destroyed in the Oklahoma bombing, and a new courts complex in Phoenix where tiny sprinklers throw a fine mist of cool water on overheated litigants in the public plaza. In recalling his Irish visit, Feiner, who is now International Operations Director with the firm of Skidmore Owings Merrill, pays tribute to another distinguished Irishman.

In the 1970s, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, in an earlier manifestation as a senior official of the Department of Housing and Urban Development, had written a simple one-page brief for the revival of the original spirit of public architecture in the Unites States. His contribution rounds off an impressive catalogue of Irish influence and achievement in the sphere of public architecture and engineering in the United States over the first 200 years of its existence.

It’s a list that includes Christopher Colles, an early Federal architect/engineer who devised New York’s first water system; Charles Cluskey, who produced plans for The Capitol and delivered several impressive projects in the South; the Galliers (father and son) and Cork-born Henry Howard. Who dominated New Orleans architecture in the early 19th century; and Jeremiah O’Rourke, the Dublinborn church architect who flourished briefly as Chief Architect to the U.S. Treasury in the 1890s.

That compendium can be set beside the ongoing record of one of America’s most acclaimed modern architects of landmark, institutional and commercial, buildings — the Dublin-born and Connecticut-based Kevin Roche, who celebrates his 83rd birthday this year, laden with honors and continuing world-wide commissions. James Hoban, who continued to work into relative old age, would be proud! ♦

Leave a Reply