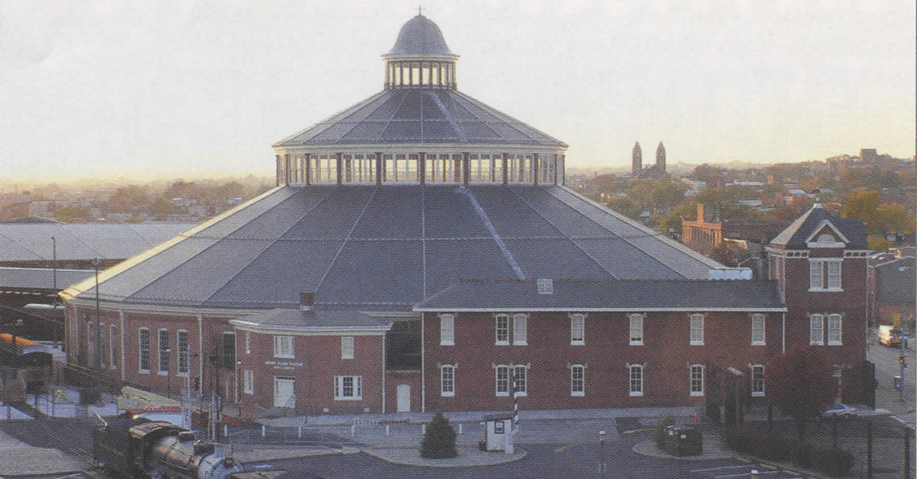

Tucked in a corner of southwest Baltimore, the grand dome of the country’s largest railroad museum looms over a run-down area that was once an Irish enclave.

On the site of the once revered but now defunct Baltimore &Ohio Railroad Company, the museum pays homage to the country’s first passenger and freight railroad. The surrounding area, which hosts a number of distinctly Irish sites dating back to the early 19th century, is a testament to the effect the railroad company had, not only on American industry, but on the history of the Irish in America.

The B&O first formed in 1827. Its construction projects, which required blasting through the Appalachian Mountains — a 25-year undertaking — delivered American capitalism from its infant stages. Needless to say, the task required intense physical labor.

“We’re not talking about little wooden bridges but great stone viaducts being built across rivers and streams,” explains Courtney Wilson, the museum’s director.

As was common with high-risk jobs in the early 19th century, few Americans wanted the job, clearing a path for the arriving Irish immigrants who did. When work began on the railroad in 1830, 60-70 percent of the work force was Irish. The B&O Railroad engineered the second largest wave of European immigration into America during the late 19th century. It brought the Irish, German, Polish and Italian immigrants to Locust Point terminals and offered them accommodations in Baltimore or the opportunity to reach destinations throughout the East and Midwest. At the outset of the Famine, the B&O had gained a global reputation, and many Irish emigrated specifically to answer the company’s call for work. The desire to work for the B&O was so great that many a swindler was born out of the immigrant’s desire to find work. It was not uncommon for Irish immigrants to be sold “certificates of employment” to work at the B&O, only to find the jobs weren’t waiting for them when they stepped off of the platform at the Mt. Clare train station.

An Irish community quickly formed around the railroad, the imprint of which is still evident today. On Lemmon Street, in an alley across the street from the museum, stand five row houses built during the 1840s. Irish families lived in each, and two of the buildings host the Irish Shrine — a monument to Irish workers which recreates the living conditions from that era — and a memorial with the names of Irish railroad workers inscribed in hundreds of bricks. St. Peter the Apostle Church, the third oldest Catholic Church in the city, and an accompanying cemetery, hosting 13,000 to 15,000 departed Irish (some head-stones beating Gaelic inscriptions), also grace the neighborhood.

In 1999, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Museum, which is dedicated to the preservation and interpretation of American railroading, joined the Smithsonian Institution’s Affiliates Program becoming the first railroad museum and the first museum in Maryland to hold that distinction. The museum is not only a landmark to the Baltimore Irish, but to Irish across the globe, including the Irish Prime Minister (Taoiseach) Bertie Ahern, who made a trip to the Irish Shrine and museum this past St. Patrick’s Day. Mr. Wilson beamed remembering the cufflinks the Taoiseach gave him on his visit.

Though the museum has been in existence, shifting through the hands of different corporate institutions, since 1893, it was closed for the last two years due to a tragic collapse of its signature round-house building during a record-breaking snowstorm. The museum was closed for 22 months while it rebuilt and raised the $30 million required to make repairs. While the museum has been open since November, and has since attracted an average of 20,000 visitors a month, a grand opening is slated for Memorial Day weekend, at which time a new 50,000 square feet of exhibit space will be unveiled. ♦

Leave a Reply